Robin writes:

I’m no fan of TV talent shows, but I have to say they offer a fascinating insight into human behaviour. Have you ever noticed, for example, how the most genuinely talented performers are taken by surprise when the judges and the audience love them? On the flip side, the worst acts appear to have no idea how bad they actually are.

Most of us like to identify with the former and laugh at the latter. But the truth is, we’re all guilty of over-estimating at abilities at something. As SAM INSTONE explains, the irony is that the less we know about any given activity, the more likely we are to overestimate our skill or knowledge.

One day in 1995, a man robbed two American banks in broad daylight. He didn’t wear any sort of disguise and smiled at surveillance cameras before walking out. The police arrested him later that night.

Interestingly enough, when the robber was handcuffed, he was puzzled and mumbled: “But I wore the juice.” Apparently, the robber thought smearing lemon juice on his face would make him invisible to security cameras. And he didn’t just think that. He was pretty confident about it.

His rationale? Since the chemical properties of lemon juice are used in invisible ink, it should render him invisible too. (This is obviously not a normal way of thinking).

But what’s interesting is that, even after the police showed him footage of his robbery, he was genuinely surprised it didn’t work.

He thought the footage was fake. The police concluded this man was not crazy or on drugs, just incredibly misinformed and mistaken.

Why are we so confident?

The funny robbery led two social psychologists, Dunning and Kruger, to study this phenomenon more deeply.

Specifically what interested them the most, was the confidence he exerted. What made him believe he’d be able to obstruct the security cameras with just lemon juice?

To investigate this, they examined a group of undergraduate students according to their grammatical writing, logical reasoning and sense of humour. They asked each student to estimate his or her overall score, as well as their relative rank compared to other students.

After knowing the actual test scores, Dunning and Kruger found something fascinating. Students who scored the lowest in these cognitive tasks, always overestimated how well they did. And not just by a little… By a lot.

They thought they had scored well above average, while their scores were actually the lowest. Not only were those students incompetent or less skilled in those areas… They lacked awareness of just how bad they were.

Students who scored the highest, had more accurate perceptions of their abilities. But, they made a different mistake. Paradoxically, the highest-scoring students underestimated their performance.

They knew they were better than average at the test. However, because it was easy for them, they assumed it was easy for everyone. They didn’t know their ability was at the top percentile.

The Dunning-Kruger effect

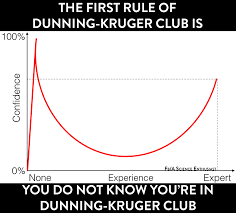

Today this phenomenon is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Essentially, low-ability people do not possess the skills needed to recognise their own incompetence or lack of knowledge.

Their poor self-awareness leads them to overestimate their own capabilities. You can clearly see what I mean in this graph here. Having barely any skill or knowledge, leads to massive confidence.

However, when you become more knowledgeable about a certain topic, that confidence falls. Only when you start to become above average in a skill, your confidence about a certain topic starts to pick up again.

Contrary to popular belief, this is not just limited to cognitive tasks. It doesn’t seem to matter what specific skill we pick. The less a person knows about any given activity, the more likely they are to overestimate their skill or knowledge.

We can’t see how bad we really are

The Dunning-Kruger effect can be observed in TV talent shows. The auditions are usually filled with a variety of good and bad singers. The ones who are bad at it almost never realise how bad they really are.

That’s why they’re genuinely disappointed when they get rejected. The truth is, we’re not very good at evaluating ourselves accurately. We’re cognitively biased.

The majority of people believe they are better than average. 95% of people think they’re better drivers than the majority. Even elderly people rank themselves among the best drivers.

A more interesting example is that 88% of investors assume they are better in comparison to their peers.

Fact: we judge ourselves to be better than others, to a degree that violates the laws of mathematics.

But why?

Why, then, does being less skilled make you more confident in your abilities? I’m going to help you visualise how this happens.

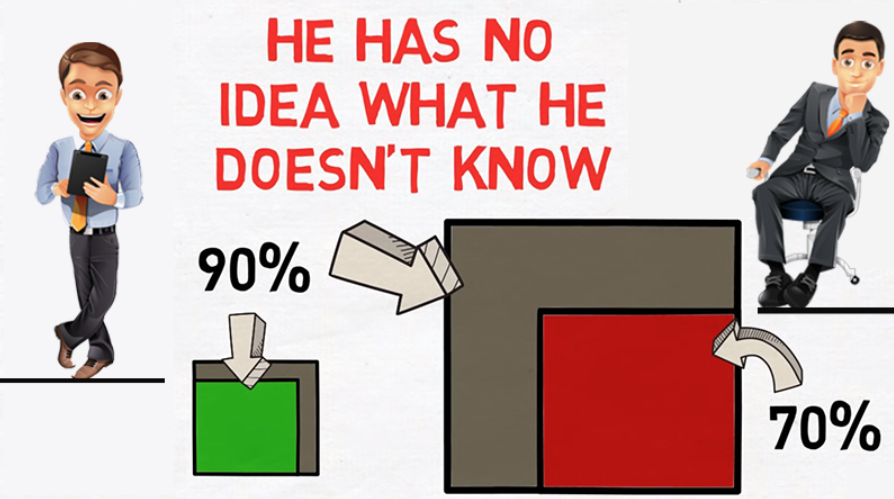

Alex is a DIY investor. He’s read a few books and subscribed to a few blogs and is now confident he knows a lot about investing. He’s bought a basket full of index funds. With this reasoning, he’s easily at the top percentile of all investors.

But let’s say he meets a professional planner, someone who has been doing it all day, every day, for ten years, and still has a lot to learn. This professional planner knows the field is much larger, and there’s much to know about it. Because he is more knowledgeable about the subject, he knows a grey area exists. However, Alex does not.

Now you can see why Alex is so confident in his ability. He has no idea, just how much he doesn’t know. Because he only has a little knowledge of the field, he doesn’t know that it’s way more extensive than that. And because he doesn’t know, what he doesn’t know, he thinks he knows 90% about investing.

Meanwhile, experts tend to be more aware of how knowledgeable they are. But they often make a different mistake… They assume everyone else is knowledgeable as well, mostly because others exert so much confidence.

In this instance, the planner is aware he only knows about 70%. But if he met someone like Alex, he would underestimate himself. 90% is better than 70% after all.

What’s the answer?

We are all susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect. It’s basic human behaviour. In fact, the first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is that you don’t know you’re a member.

But how can we prevent ourselves from falling prey to it?

Well, the answer is… You should strive to educate yourself as much as possible.

You’re not expected to know everything after all. But thinking you’re always right is foolish.

It seems the more knowledge people have, the more they realise how little they know in reality.

In other words, the more people know about a certain issue, the more they realise how complicated, unexplored and extensive it is. And how many things they do not understand or know yet.

A beautiful paradox

It’s a beautiful paradox in which the more we study something, the less we know about it. On the other hand, people who dabble on the surface of anything they pursue, will never know how much they still have to learn.

In the Dunning-Kruger experiment, unskilled or incompetent students improved their ability to correctly estimate the test results after receiving minimal tutoring on the skills they lacked. It’s helpful to have someone who is ahead of you show you what you have yet to learn.

So next time you feel confident you know a lot about something, take a closer look at the topic. It could be you are a victim of the Dunning-Kruger effect. You just might not know what you don’t know.

SAM INSTONE served as a British Army Officer in the Household Cavalry Regiment before founding AES International. Based in Dubai, AES is an evidence-based financial planning firm serving UK expats around the world. The firm is a strategic partner of TEBI and supports our work in the United Arab Emirates.

This article first appeared on the AES blog and is republished here with Sam’s kind permission.

For more information about AES international and its investment philosophy, we suggest you visit its YouTube channel.

Want something else to read? Here are some more articles we think you’ll find interesting:

Is there a link between intelligence and performance?

Index funds 43 College endowments 0

Why failed predictions are soon forgotten

The case for global diversification is as strong as ever

You don’t need to know the future to invest successfully

Picture: Luke Tanis via Unsplash