Greenwashing: How widespread is it?

Comments Off on Greenwashing: How widespread is it?

ESG investing has grown hugely in recent years. But a lack of consistency in product labelling and disclosure has raised investor fears that sustainability claims made by fund providers might be overstated or unreliable. But what evidence is there that so-called “greenwashing” is as widespread as some commentators fear? New research by S&P GLOBAL suggests that, although there is still much room for improvement, the problem is not as serious as you might think.

ESG has become mainstream. In the wake of this trend, key stakeholders, including consumers and investors have started pressuring companies to demonstrate their ESG credentials either through commitments and actions at the corporate level, the products they offer, or the instruments they use for financing. Governments and regulators have also introduced enhanced standards and regulations to support increased disclosure and consistency of ESG reporting.

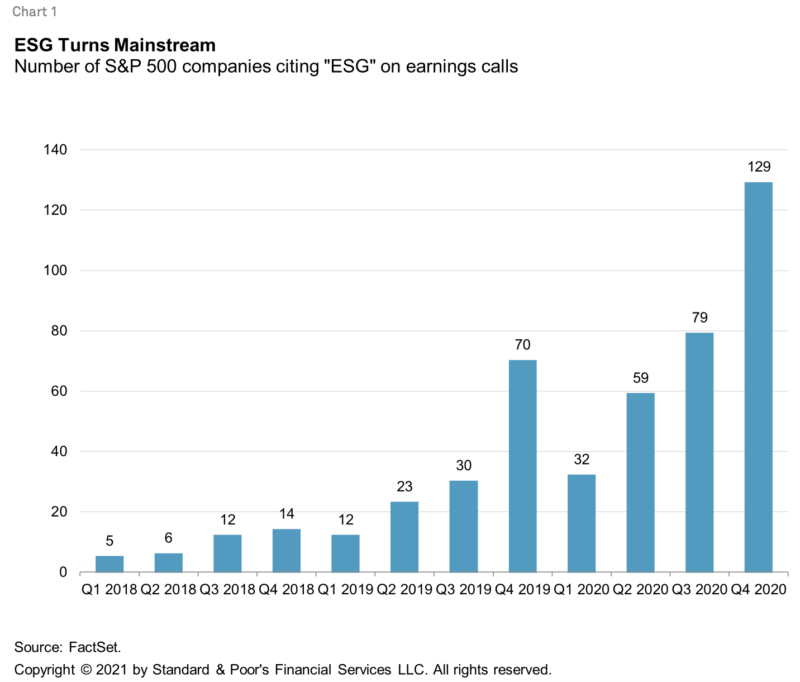

This ESG push, which has been propelled by legitimate risks and concerns important to market participants, has led to an inevitable and exponential rise in the volume of green claims made by companies in their attempt to demonstrate sustainability credentials to their stakeholder base (see chart 1). However, the sheer volume of ESG marketing and labelling, in combination with nonuniform sustainability commitments and reporting, has made it increasingly difficult for stakeholders to identify which claims are trustworthy and reliable and which are unreliable — or, in industry terms, “greenwashed.”

What is greenwashing?

The term greenwashing was first coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in a 1986 essay in which he claimed a hotel was encouraging consumers to reuse towels to help protect the environment, when in reality the ask was a marketing ploy to help the hotel cut costs and improve its profit margins. The term gained prominence in the years following as consumer and media attention to environmental risks gained traction, leading to an influx of environmental marketing and product labelling campaigns to capitalise on the growing demand for “green” products.

Over time, the definition of greenwashing has morphed. While in Jay Westerveld’s example, environmental benefits were still ultimately achieved despite the primary motivation being cost-cutting, concerns about greenwashing have become broader in scope with companies perceived to be making exaggerated or misleading environmental claims, sometimes without offering significant environmental benefits in return.

As ESG grows, so does investor scrutiny

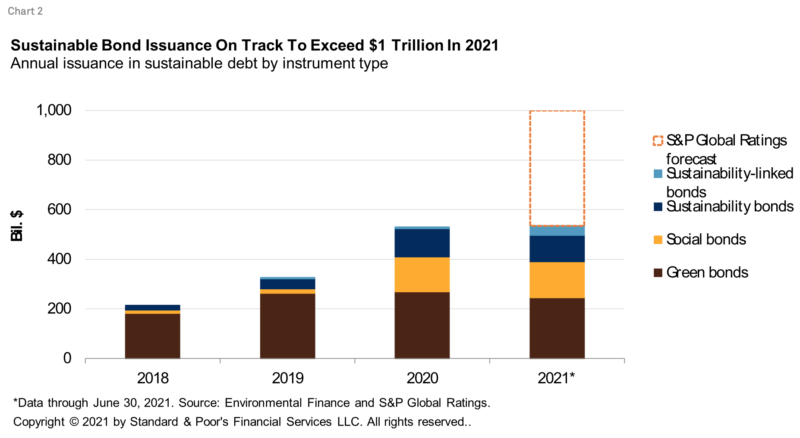

The mainstreaming of ESG has had a galvanising impact on how sustainability factors are incorporated into investment decisions, including at the financial instrument level. S&P Global believes sustainable bond issuance, including green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds, could collectively exceed $1 trillion in 2021, a near 5x increase over 2018 levels.

Despite this impressive growth trajectory, a lack of transparency around instrument labelling, reporting, and data disclosure leaves many stakeholders asking whether greenwashing has tainted those numbers. A survey conducted by Quilter Investors in May 2021, found that when it comes to ESG investing, greenwashing was the biggest concern for about 44% of investors. According to the survey, investors looking to act more responsibly and maximize their environmental impact have become “increasingly sensitive” to the effects of companies potentially viewed as exaggerating their green credentials to capitalise on the growing demand for environmentally safe products.

Naming conventions lack uniformity

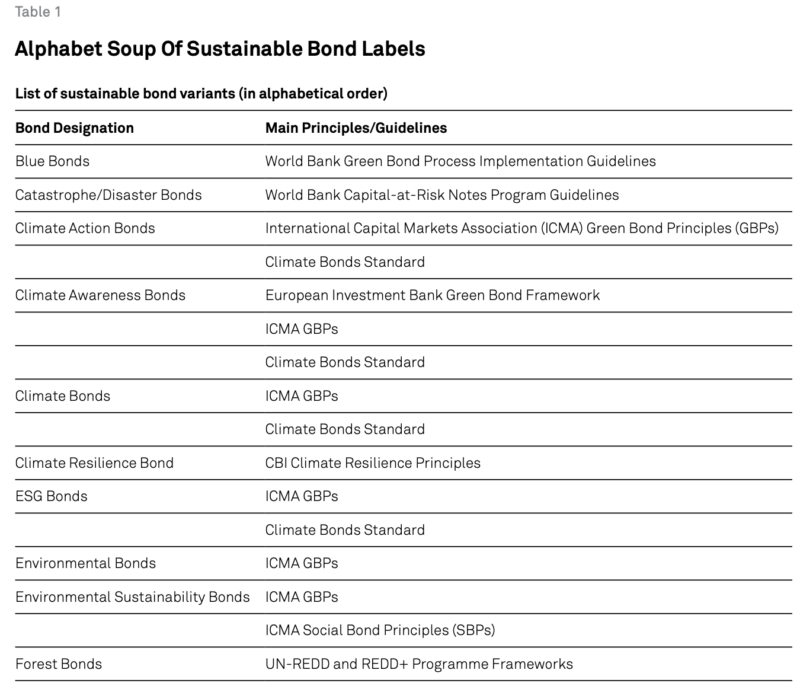

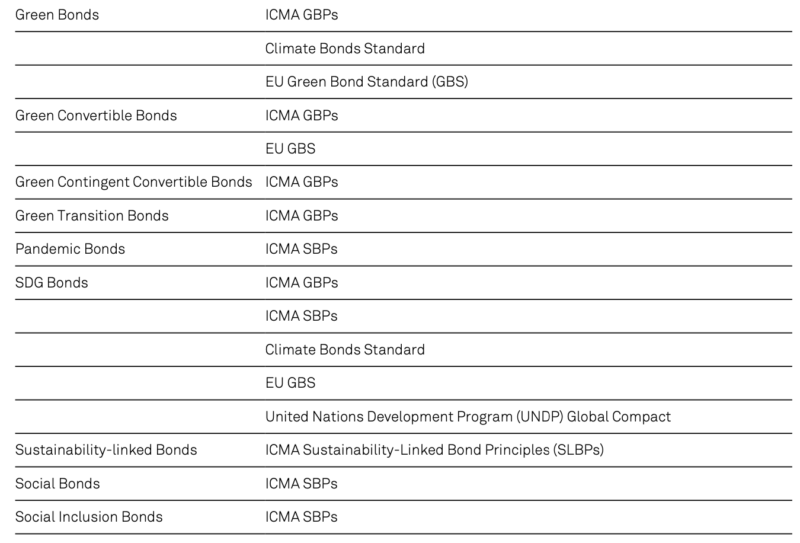

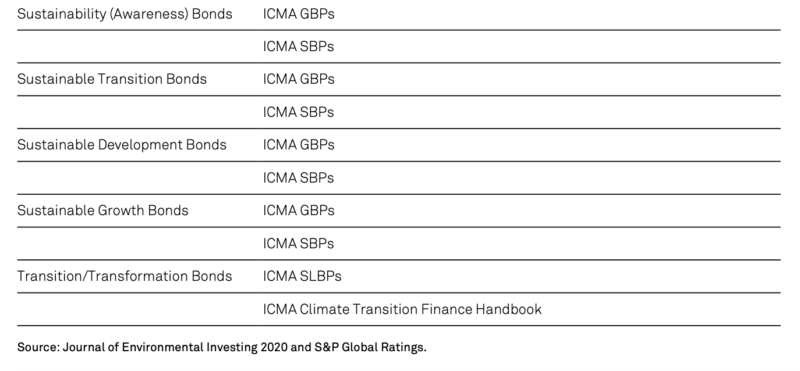

A lack of consistency in ESG terminology associated with various ESG investments has become a key concern that may drive investor confusion when it comes to identifying which companies or financial instruments conform to a given set of ESG standards. According to the Journal of Environmental Investing Report 2020, there are more than 20 different labels being used for sustainable debt instruments, which all align with different guidelines or frameworks (see table 1). The wide scope of labels and even wider scope of what constitutes a “green” or “social” project makes navigating the sustainable debt space increasingly complex for investors and reduces comparability across instruments.

Inconsistency in disclosure is still an issue

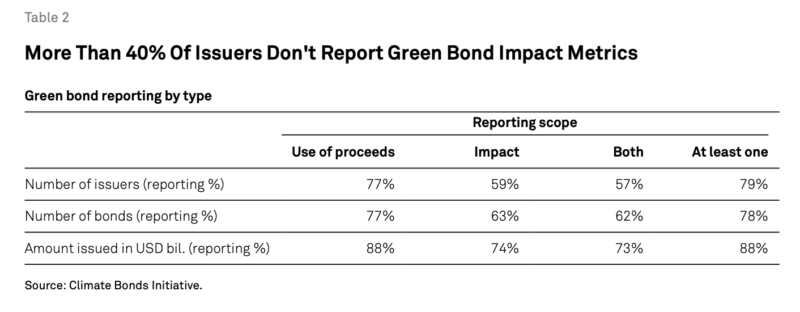

A lack of reliable and comparable ESG metrics and reporting is another key challenge to tackling confusion in the ESG space. In the absence of a common standard and enforcement mechanism for instrument-level ESG disclosure, the quality and consistency of post-issuance use of proceeds and impact reporting is still highly unstandardised and fragmented across issuer types and regions making it difficult to compare and aggregate performance. According to a report published by the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) in May 2021–based on a review of all green bonds in the Climate Bonds Database issued between November 2017 and March 2019–only 77% of green bond issuers published on the allocation of proceeds and only 59% quantified the environmental impact of the projects financed (see table 2).

In addition, the lack of uniformity in impact data along with the widespread adoption by issuers of relative, rather than absolute performance metrics, obscures the “full picture” of performance. This has made it more difficult for investors to measure the ESG-related impact of financed projects. In turn, this creates a concern that green bonds aren’t financing new projects that provide a significant environmental benefit, referred to as “additionality” of the bonds. In our experience, a high proportion of green bond issuance has been used for refinancing existing assets or projects. However, issuers of these bonds don’t always disclose a defined refinancing look-back period in their frameworks or financing documentation, meaning projects being refinanced could have originated many years ago and therefore no longer qualify as new green investments.

While CBI acknowledges there’s more work to be done in the standardisation of the green bond market, it has ultimately concluded that greenwashing overall remains rare as issuers genuinely finance green projects and assets.

Green bond reporting by type

“Sustainability-washing” concerns rise

Despite initial investor fears of greenwashing being quelled as the market becomes more mature, so-called “sustainability-washing” concerns have become increasingly prominent as new types of sustainable financing, including social, transition, and sustainability-linked instruments, take root.

Social bonds

Social bonds, which finance projects with primarily social objectives, have raised concerns around “social washing” —the risk that an issuer may be viewed as overstating or exaggerating the social impact of its financed projects. The largest challenge for the social bond market is measuring impact. Social impact tends to be more qualitative in nature and less-well defined, making it harder to track and disclose metrics for social projects. Because there are few standardised measures of social impact, many of the so-called “impact” indicators reported by issuers are actually measures of input, such as dollars spent, loans issued, number of participants, or hospital beds added as opposed to measures of improvement in social outcomes. This had led to a level of vagueness and a lack of transparency in issuer disclosures, increasing investor skepticism that issuers are using proceeds for projects without additional social benefits.

In addition, with the acceleration of social bond issuance over the past year, largely catapulted by the COVID-19 pandemic, speed to market became the most important factor, with many issuers foregoing development of a social bond framework or external verification and review, as recommended by the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) Social Bond Principles (SBP). Therefore, improvements in tracking and disclosure have experienced a significant lag compared to the more mature green bond market.

Transition instruments

Furthermore, issuers in energy-intensive, hard to abate sectors are increasingly leveraging sustainable or “transition” instruments to help them advance their contribution to a net-zero emissions economy (see: “Transition Finance: Finding A Path To Carbon Neutrality Via The Capital Markets,” published March 9, 2021).

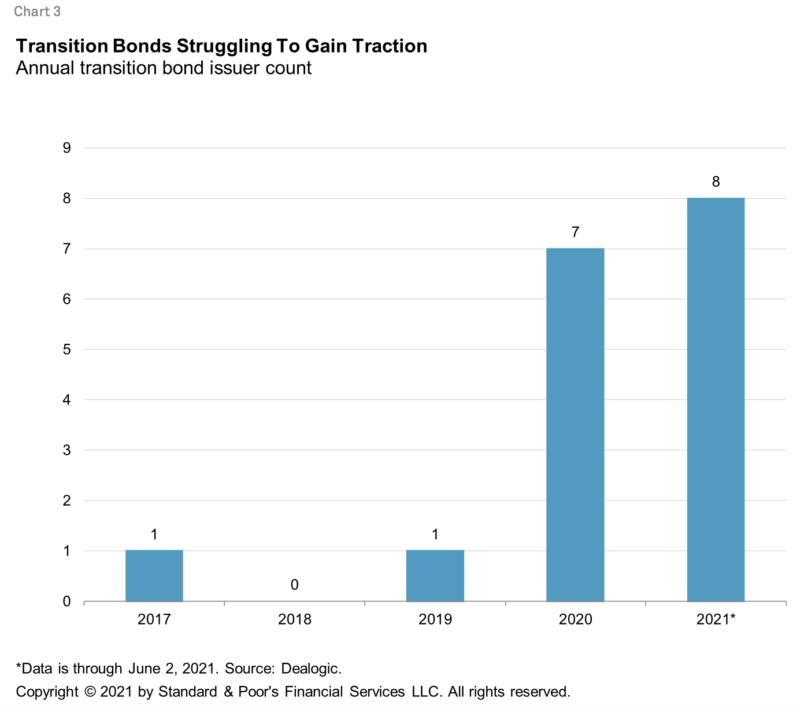

Growth of the transition finance market has elevated greenwashing (or “transition-washing”) concerns because such instruments are often characterised by a lack of clarity and common terminology on what is considered to be a transition activity or project. For example, concerns may be raised that a transition instrument is financing projects that don’t significantly improve an issuer’s environmental profile. Issuers of transition finance instruments may also be criticised for lacking ambition and having weak or superficial sustainability commitments that represent little more than a continuation of “business as usual” practices, which actually have a deleterious impact on national or corporate greenhouse gas-emissions (GHG) goals. Such concerns, we believe, have undermined the growth of the transition finance market with only 16 transition bond deals recorded as of June 2021 according to Dealogic.

The “Just Transition” accelerates

Key to sustainable development is the emphasis on environmental and social projects that enable a transition that is equitable and limits indirect or knock-on harmful effects on individuals, communities, or other stakeholders. Examples of such knock-on effects may include the displacement of labor or local community members as the transition to low carbon forms of energy accelerates, natural capital impact of economic development or access to essential services projects, and penurious interest rates in access to finance projects. We believe the emphasis on this so-called “Just Transition” has placed the onus on issuers of sustainable debt instruments to identify and mitigate environmental and social risks associated with their financed projects to ensure that the benefits are shared evenly across the economy.

Sustainability-linked instruments

It’s not just use of proceeds instruments that are susceptible to sustainability-washing concerns, though — similar concerns also extend to sustainability-linked debt instruments, such as sustainability-linked bonds and loans. The structure of sustainability-linked instruments, which allows issuers to use the proceeds for general corporate purposes, has elevated investor fears that proceeds may directly fund projects without a clear beneficial impact, making them a new platform for green or social-washing.

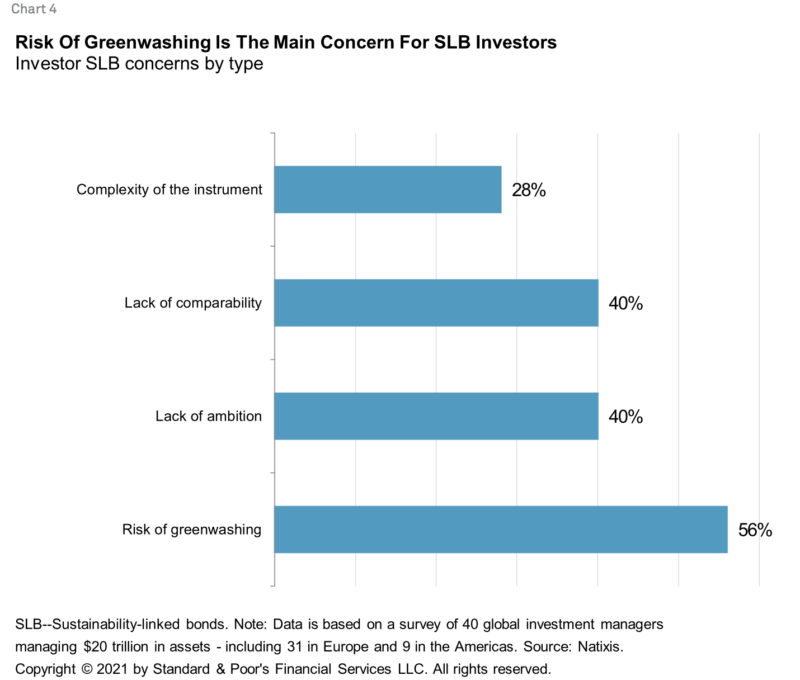

Investors primarily remain concerned that issuers of sustainability-linked instruments may set sustainability performance targets (SPTs) that aren’t sufficiently ambitious (i.e. they don’t demonstrate a significant improvement over the issuer’s business-as-usual strategy or require significant investment to be achieved) (see chart 4). For example, an issuer of a sustainability-linked instrument might already be close to achieving their set targets at the point of issuance because performance improvement is based on an old baseline. Other concerns may surround comparability and reliability of often self-policed and unaudited performance data against issuer’s set goals and targets, particularly in the absence of a globally accepted methodology for reporting on the SPTs. Similar to the use of proceeds instruments, concerns may also exist with more qualitative social metrics as well as key performance indicators (KPIs) which are internal or idiosyncratic in nature, making comparability cross-issuer and cross-sector more difficult. Such challenges have increased calls for issuers to establish performance targets supported by science-based scenarios or demonstrated proxies or aligned with regional or international goals.

Actions speak louder than words

In our view, investor scrutiny of the transparency, robustness, and credibility of sustainability commitments will continue to become bolder and broader in scope. We anticipate this will be true at the individual instrument level and at the entity level. It’s becoming clear that entities can no longer simply state their sustainability goals or long-term targets. Stakeholders want to see companies produce detailed transition action plans, backed by data and shorter-term interim targets, which demonstrate strong commitments toward a more sustainable future. Ultimately, we believe that companies that can substantiate their environmental claims, and align financing with a business strategy rooted in long-term ESG goals, will be better fit to withstand potential reputational, financial, and regulatory sustainability-related risks that will evolve over time.

Harmonisation of regulation is needed

While demand for sustainable financing instruments remains very strong and promises to increase, concerns around the accuracy of issuer sustainability claims can have profound impacts on the integrity and development of the sustainable finance market. In response to this risk, a number of standards and taxonomies have recently emerged that attempt to help standardise the market and mobilise capital toward sustainable objectives. The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) and the Loan Syndication Trading Association/Loan Market Association/Asia Pacific Loan Market Associations have launched a set of principles to promote standardisation and transparency for use-of-proceeds and sustainability-linked bond and loan markets (the Principles). While the Principles are voluntary, an estimated 97% of use of proceeds and 80% of sustainability-linked bonds issued globally adhered to them in 2020 according to ICMA and Environmental Finance, which has helped enhance credibility and integrity in the market.

While not directly focused on sustainable debt instruments, disclosure standards such as the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) have also helped mitigate greenwashing concerns by helping investors understand how organizations assess the financial impact of physical and transition climate-related risks and opportunities. According to the World Bank, the TCFD has increased transparency and reduced costs incurred by investors as they search for sustainable investments, making it easier for them to compare across various financial products.

The EU is driving standardisation in disclosure

At the regional level, the EU has been leading the charge, propelled by the European Commission’s Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth, adopted in March 2018, which sets out a roadmap for Europe’s transition to a low-carbon economy. Since adoption of the “Action Plan,” a number of regulatory initiatives have been proposed to support the EU’s efforts. Among the most prominent is the EU Taxonomy Regulation, which provides a classification system for economic activities to be considered “environmentally sustainable”(see: A Short Guide to the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation, published May 12, 2021). The Taxonomy is a major step in creating a more unified language around sustainability and promoting greater availability and reliability of ESG data and disclosures to investors and other stakeholders.

In addition to the EU Taxonomy, the EU has also adopted regulation addressing ESG reporting obligations such as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which requires financial market participants to disclose how they take sustainability risks and adverse impacts into account at the entity and product level, with the primary goal of avoiding greenwashing in financial products (see: What is the Impact of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)? published April 1, 2021).

Most recently, the European Commission also introduced a proposal for a voluntary EU Green Bond Standard designed to create a common standard for how public and private entities use green bonds. Under the proposed standard, projects financed by a bond using the European green bond or EuGB designations must be in line with the EU Taxonomy to be eligible. In addition, issuers will be required to provide full transparency on how bond proceeds are allocated according to detailed reporting requirements and engage an external reviewer registered with the European Securities Market Authority (ESMA) both pre- and post-issuance to comment on the extent to which the funded projects are aligned with the Taxonomy.

The EU has also proposed a sweeping new set rules in the form of a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The CSRD proposes to amend the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and aims to introduce a detailed rulebook for how large companies operating in the EU disclose both their sustainability risks and their impact through the lens of “double materiality”.

We believe these policy efforts, when adopted, could eventually have spillover effects into other parts of the sustainable finance market such as social, transition, and sustainability-linked instruments.

Progress towards global standardisation

Despite the progress being made in the EU to mandate, increase, and standardise ESG reporting — which, in turn, we believe will help mitigate greenwashing concerns — the road to standardisation globally is likely to be relatively long. There is still considerable fragmentation in regulations and taxonomies that limits comparability across regions. In the Asia-Pacific region, for instance, countries such as China, Singapore, Malaysia, and Mongolia have each established their own stand-alone green taxonomies that largely follow local regulations.

In addition to varying widely within the region, most of these taxonomies also differ from European or international standards. For example, the China Green Bond Catalogue — which was established to govern China’s green bond market — defines more than 200 specific project categories with unique eligibility criteria, differing substantially from the EU Taxonomy where eligibility criteria is instead governed by four broad principles.

Furthermore, the U.S. has taken a different approach entirely, requiring companies to disclose climate risks in securities filings if they deem such risks material. Specific environmental or social impact reporting isn’t currently mandated. In the U.S., there also aren’t any formal definitions for what qualifies as a sustainable activity and there are currently no uniform standards for measuring corporate environmental goals or quantifying and reporting climate risks. However, we understand there are plans to provide a framework for some form of disclosure on specific climate and human capital matters in the future.

There are efforts being led toward establishing better standardisation and harmonisation. The EU and China, for instance, are working to establish a Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT) through the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (ISPF) to unify their green finance standards under a common approach and address inconsistencies among the regional taxonomies. In addition, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation has proposed setting up an International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) to lead the mainstreaming of sustainability reporting on an international level. We anticipate that these baseline standards will adapt norms set by the TCFD framework and existing work of other sustainability standards.

Harmonisation as the way forward

As green taxonomies continue to be developed across the globe, the challenge will be finding a way to maintain global harmonisation. This will be a combined effort of industry organizations, governments, standard setters, consumers, and other stakeholders. Meanwhile, as standards evolve, entities will be held increasingly accountable for their sustainability commitments. We anticipate that investors and regulators will increase their scrutiny on sustainability statements, particularly as reporting and disclosure standards get more prescriptive over time. The effects of this may ultimately spill into the capital markets, potentially limiting access or increasing the cost of capital for those issuers that are unable to make or deliver on their sustainability claims.

Increasingly, sustainable finance instruments will become more diverse and nuanced, in part to accommodate the new reality: that each sector, even those that are hard to abate, must contribute to decarbonisation if the most dire consequences in the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report are to be avoided. One tool for managing the risk of potential greenwashing, and ensuring issuers are held accountable for their sustainability commitments, is information: investors should have the tools to scrutinise different sustainability metrics and understand and discern the factors that are most material to them, both from a financial and from a broader ESG perspective. We believe that greater investor demand for more detailed and consistent ESG disclosure will continue to drive improvements in this field and add momentum to the evolution of ESG-focused regulatory disclosure and reporting frameworks.

PREVIOUSLY ON TEBI

Book-to-market: Is its explanatory power declining?

Why young investors should embrace EBI

Which country will outperform next is irrelevant

Image: Markus Spiske via Unsplash

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXI