By PRESTON McSWAIN

A message like the following is being delivered over and over to individual investors and trustees:

To be a good fiduciary of wealth, you need to “join the [endowment] club” and “place 40% or more” of your assets into private investments.”

Tugging on the yearning to provide for the “benefit of generations to come,” families are urged to invest like endowments.

For many years now, we’ve looked at how well a simple global 60% equity and 40% bond index fund portfolio has performed versus the top endowments that investors are being encouraged to follow.

Based on the results, we’ve suggested that these “need-to-do” proclamations go too far.

A few people have nudged back, saying endowments shouldn’t be compared to model portfolios of index funds. We appreciate this and agree to some extent as endowments can have different objectives, time horizons, and cash flow needs.

However, as long as we keep seeing presentations suggesting that families and individual investors “need” to invest like endowments…

We say comparisons like this are fair game.

The results

First, the good news for family endowment model fans.

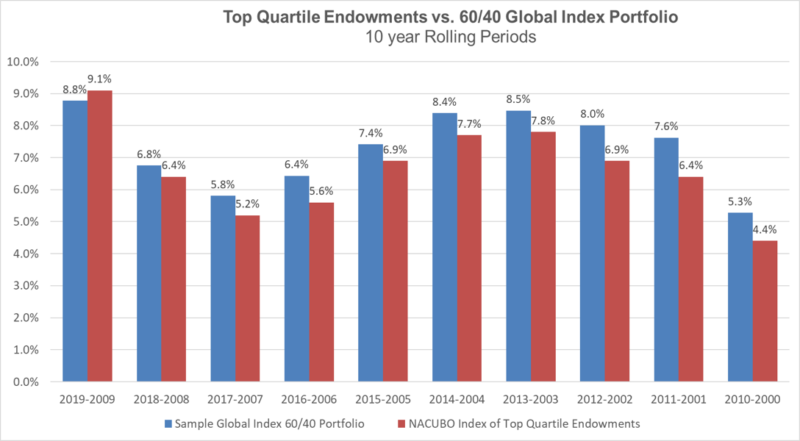

For the first time spanning the years 2000-2019, top quartile endowments seem to have outperformed a simple global mix of index funds over a 10-year period.

Below are the results.

The simple 60/40 global index fund portfolio illustrated below, which had outperformed 75% of all U.S. endowments 9 out of 9 times, for every single trailing 10-year period from 2000-2010 to 2008-2018, has dropped out of the top quartile for the 10-year period ending 2019 (8.8% vs. 9.1% – close but below).

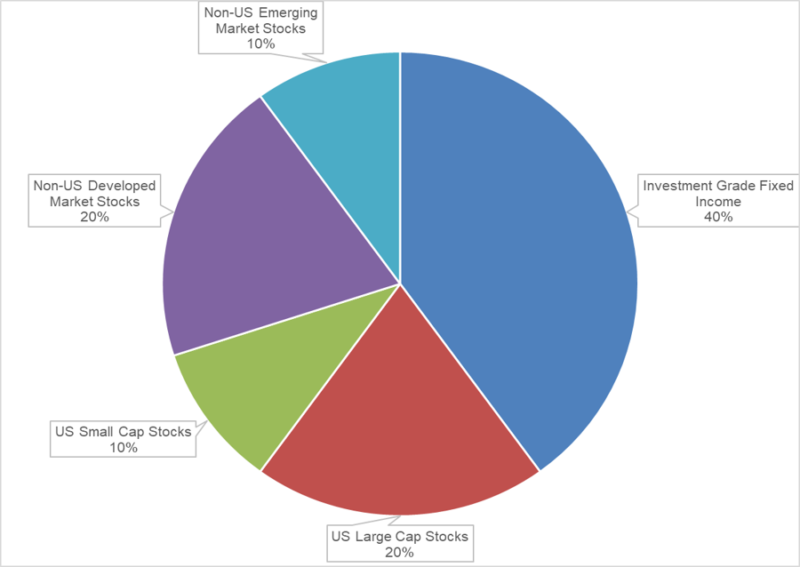

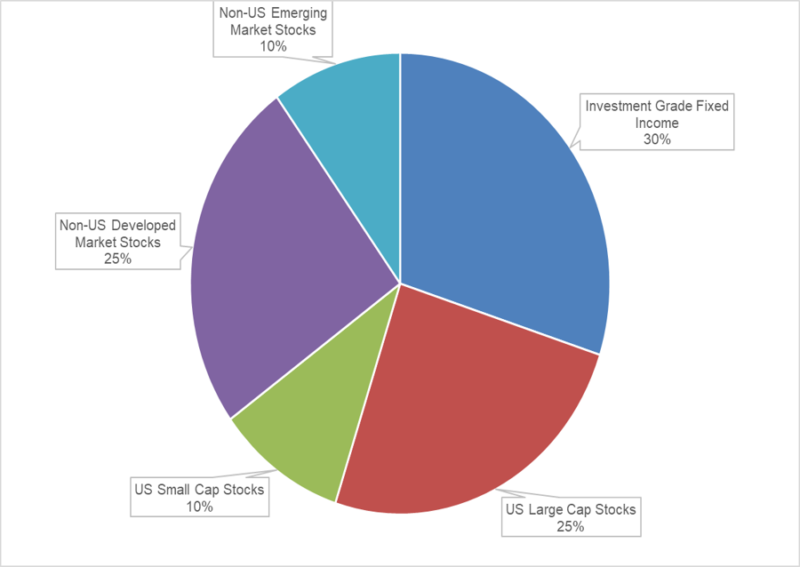

60/40 global index fund-only portfolio

Relative performance over multiple 10-year periods

Sources: MPI Database and Stylus software, Morningstar mutual fund performance data collected by MPI, The National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO – see important disclosures and details at the bottom of this post). Endowment returns and comparisons are for endowment June 30 fiscal year end reporting periods.

While this may embolden more “need-to-do” presentations, my question after looking even closer at the data this year, is this:

Over this time period, has a simple 60/40 global index fund portfolio ever been an appropriate benchmark for the endowments that individuals are being encouraged to follow?

Consider this:

For many years, large U.S. endowments and foundations have been reporting increased allocations to private equity and other types of investments, which have equity like risk and, hopefully for them, attractive equity-like returns.

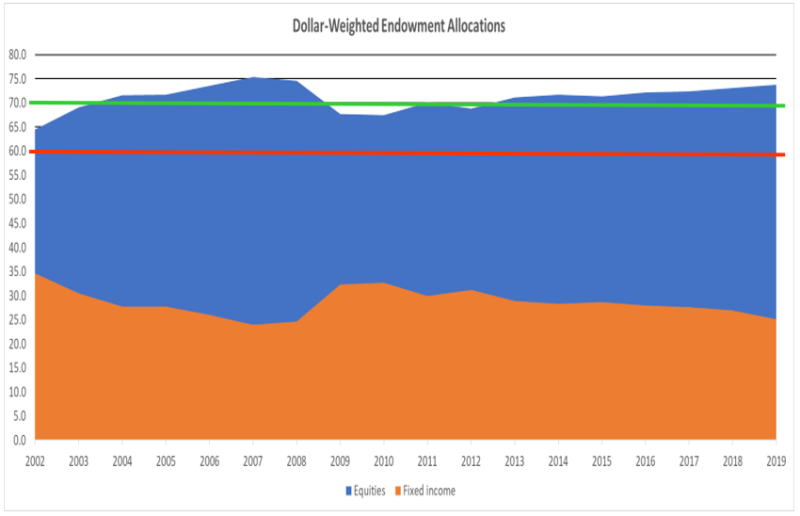

As an example, below is a chart of rolling, asset weighted allocations of U.S. endowments and affiliated foundations according to The National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) Endowment Study since 2002 (as far back as the data allows).

Endowment allocations over time

Source: NACUBO Study of Endowments

As this chart illustrates, even though some endowments report performance as compared to 60% equity and 40% bond benchmarks, it doesn’t seem to have been a good proxy for quite some time.

For the majority of the last decade, and previous to the financial crisis, 70% equities and 30% bonds might have been a better comparison.

Assumptions are key in all of this and debate could be had about how much equity like risk and return potential exists inside top quartile endowments.

NACUBO has historically lumped alternatives together in various ways, although in 2019 their Endowment Study made things a bit easier by including a category called “Other Equities.”

This category included Private Equity, Venture Capital and other Marketable Alternatives. Even though the word “Equities” was used, we assumed that not all alternatives are equity-like (80% was allocated to equities and 20% was allocated to bonds).

What’s the best proxy over all of these time periods for families to consider?

Heated banter will continue for sure.

But, based on the trend line of equities, and taking into account the red line marked above, which indicates 60% equities and the green line that highlights 70% equities, a higher allocation than 60% to stocks seems appropriate.

Assuming higher allocations to equities or equity like investments have been the case over these time periods, what happens to our comparisons when we move our index only allocations to 70% in global equities?

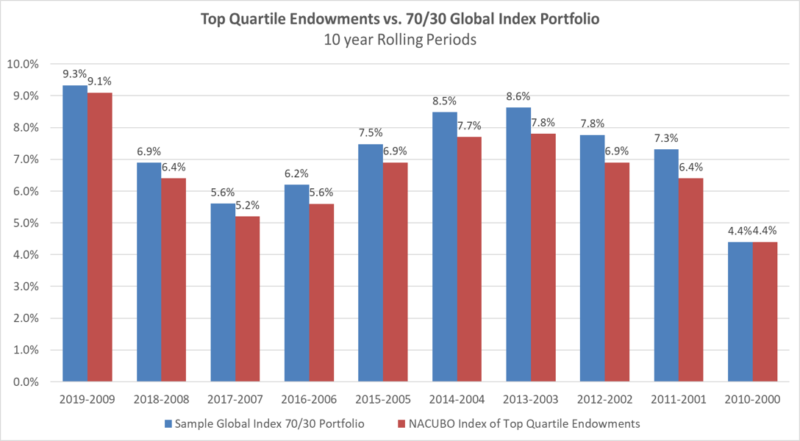

Ten out of ten

The following 70% global equity and 30% bond index portfolio re-balanced only once a year on January 1st (the methodology we have used in the past) has performed at the top quartile level – ten out of ten times – for every 10-year period spanning 2000-2019.

And for those who are wondering, a 65% global equity and 35% bond index portfolio also has ranked in the top quartile for each 10-year period.

70/30 global index fund-only portfolio

Relative performance over multiple 10-year periods

Sources: MPI Database and Stylus software, Morningstar mutual fund performance data collected by MPI, The National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO – see important disclosures and details at the bottom of this post).

This all takes us back to the title of this piece:

Do families need endowment-style portfolios?

We say no.

Either way we’ve cut it, simple mixes of index funds re-balanced in a simple fashion have consistently outperformed more than 75% of the endowments families are being encouraged to follow.

Many endowments are doing a great job on behalf of their beneficiaries.

This piece is not meant to suggest otherwise.

In addition, we aren’t proposing that all families invest solely in index funds and that all endowment-style private and alternative investments aren’t appropriate. Some are.

Our point is that the allocations of top endowments should not be used to emotionally pronounce to individual investors and families that private and alternative investments are needed.

The comparisons we make are far from perfect, and as we’ve mentioned, individuals and families can have different objectives and circumstances (differences in liquidity needs, tax profiles, levels of access, investment backgrounds, etc.).

However…

As long as endowment style portfolios continue to be promoted by the leaders of private client groups as a “need-to-do, not a nice-to-do.”

And…

Families are told that “life can be better after 40%” or more allocated to large endowment style private investments for the “benefit generations to come,” we’ll keep citing these keys to Unconventional Success.

“Only extraordinary circumstances justify deviation from a simple strategy…”

And:

“When you look at the results on an after-fee, after-tax basis, over reasonably long periods of time, there’s almost no chance that you end up beating an index fund. The odds are 100 to 1.”

– David Swensen, Chief Investment Officer, Yale Endowment

What’s the bottom line on what’s needed?

The next time you hear that you “need to” invest like a top endowment to achieve top returns on behalf of your family, maybe this response is needed:

“That just ain’t so.”

Thank you, Mr. Twain.

PRESTON McSWAIN is a Managing Partner and Chief Investment Officer of Fiduciary Wealth Partners. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, FWP is an evidence-based financial planning firm that aims to provide transparency, simplicity and peace of mind for high-net-worth individuals.

Here is a handful of Preston’s previous articles for TEBI:

Beware private equity funds that muddy the waters on performance

Calm down. We’re not all going to die (at least, not yet)

Lies, damned lies and private equity performance