By LARRY SWEDROE

The use of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) has exploded recently, in many ways to the benefit of investors. They benefit from the structure of ETFs because they can operate more tax efficiently than mutual funds. They also generally have lower operating costs than mutual funds, resulting in lower expense ratios.

Within the ETF world, leveraged and inverse ETFs have also exploded. Leveraged funds, often called “ultra” funds, attempt to capture two or three times the daily return of an index. Inverse ETFs, also called “short” ETFs, attempt to capture -100 percent, -200 percent or -300 percent of the daily return of an index. These products exist for various indexes, including broad market indexes (like the S&P 500), sector-specific indexes or even certain commodity indexes (like oil and gas). In May 2017, the SEC even approved a request to list quadruple-leveraged ETFs. These funds will target a return that is four times the daily return of a broad index.

Leveraged funds may seem like a good idea. If we expect the returns of the S&P 500 to be positive, getting four times the return is even better. However, long-term investors (there shouldn’t be any other kind) should be sceptical.

The key point to emphasize with leveraged funds is that they attempt to capture some multiple of the daily return of an index. Investors should question whether these funds are able to achieve their objective. Another question for investors is whether the capture of the daily multiple translates into long-term results. Daily returns are for speculators and day traders, but investors care about how the performance fits into their overall portfolio.

To capture the higher returns, leveraged funds use a variety of derivative products, including futures, swaps and options. This type of strategy is for traders who want to make a tactical move to capture some anticipated move in the market. However, these funds capture a multiple of both the good and the bad—if the daily return of the S&P 500 is -2 percent, for example, then the two times return fund would return -4 percent.

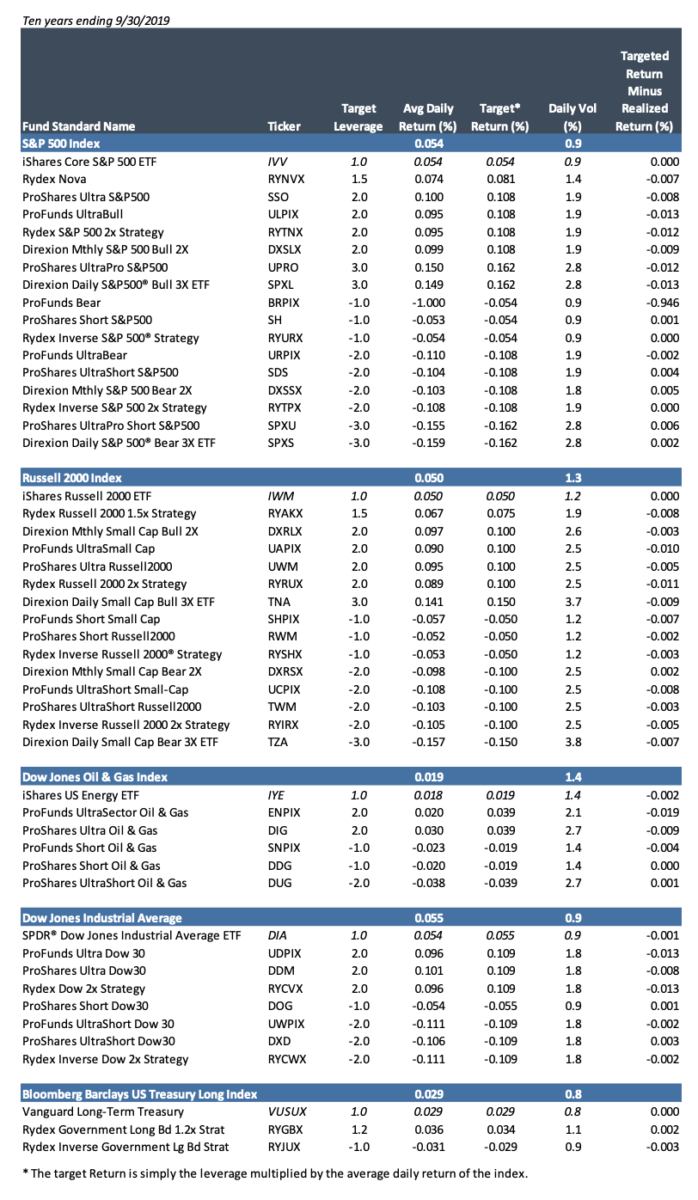

Practically, this means we expect much higher volatility from leveraged funds. To see the impact of this increase in volatility, along with the higher operating costs from employing derivatives, my colleague, Sheldon McFarland, reviewed ten years of history for some of the largest leveraged and inverse ETFs compared to their indexes. Data is as of September 30, 2019. For funds that had multiple share classes over the entire period, we used the lowest-cost share class. Funds were grouped by index, and we made every effort to present all leveraged funds that had sufficient history that track the specific indexes. Data is provided by Morningstar and the statistics are calculated from returns retrieved from Bloomberg.

First, we consider how effective the strategies were at capturing the daily return of the target index. For context, we also present one low-cost ETF that tracks the target index and that was available over the entire period.

Given that each of these funds targets a certain multiple of the daily return of the index, we expect the average daily return to roughly equal the leverage multiplied by the average daily return of the index. For example, the ProFunds UltraBull Fund (ULPIX) targets twice the daily return of the S&P. Thus, because the average daily return of the S&P 500 was 0.054 percent over this period, we would expect the fund to have provided a daily average return of roughly 0.108 percent. While the fund did produce twice the daily volatility, its 0.095 percent daily return fell short of the objective.

What we find is that even on a daily basis, most of the funds were not able to fully capture their objective return over the last ten years. Of course, part of the shortfall is explained by the funds’ expenses. Returning to our example, ULPIX’s net expense ratio of 1.40 percent is way above the 0.04 percent expense ratio of the iShares Core S&P 500 Index ETF (IVV). In other words, investors are not being fully compensated for the greater volatility risk.

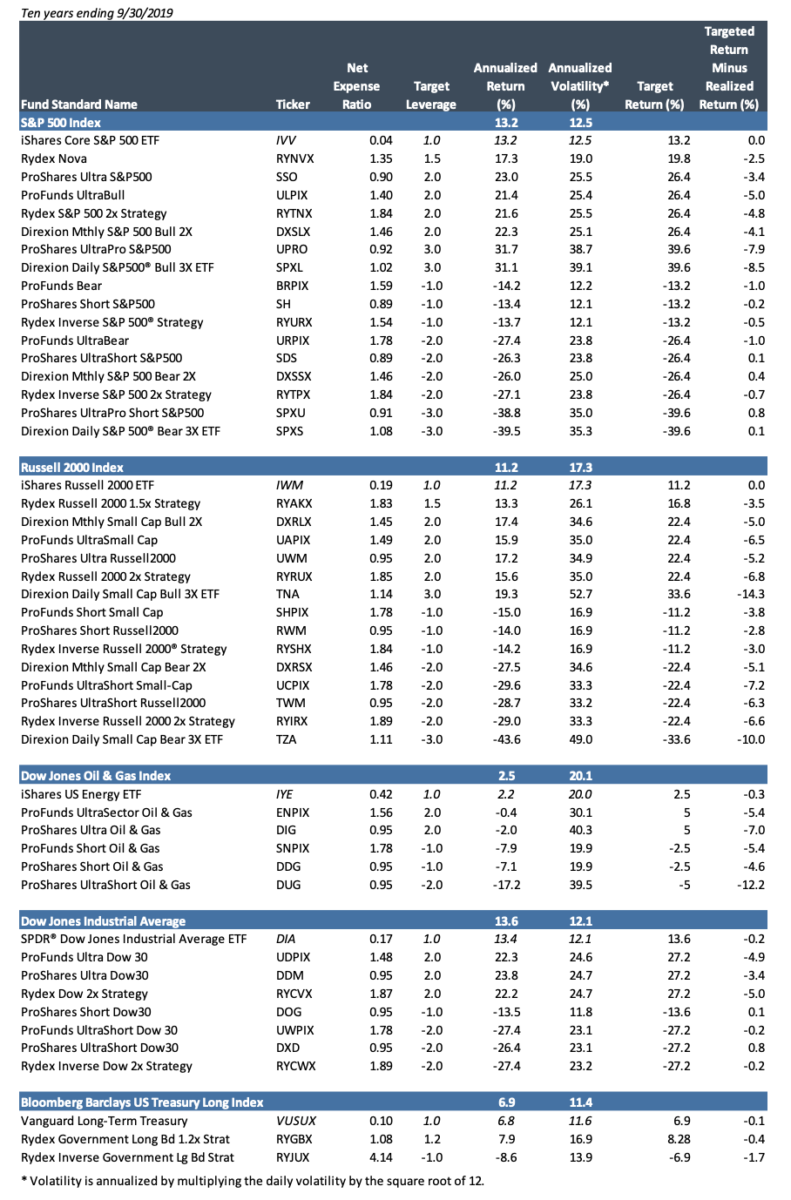

Given the difficultly in meeting the daily return objective and the higher volatility, investors should be skeptical about how these funds translate into a long-term strategy. In looking at the ten-year total return of the funds compared to the target strategy, we find the skepticism is well-founded. As you review the results, keep in mind that leveraged funds that had positive exposure to equities benefited from the decade-long bull market, with the S&P 500 Index returning 13.2 percent.

As you can see, leveraged funds failed to achieve their target return multiple. For example, the ProShares Ultra S&P 500 ETF (SSO) returned 23 percent, or 3.4 percentage points below the targeted return of twice the index. The expense ratio only explains 0.9 percentage point of the gap. The similar ULPIX, with an expense ratio of 1.40 percent, returned 21.4 percent, underperforming its targeted return of twice the index by 5 percentage points.

Some ETFs even failed to achieve the returns of the unlevered index. For example, the ProFunds UltraSector Oil & Gas Investor ETF (ENPIX) returned 0.4 percent per year compared to 2.5 percent for the Dow Jones Oil & Gas Index. Thus, it underperformed the index by 2.9 percentage points per year over the ten-year period while experiencing significantly more volatility! Conversely, if an investor had put their money into a simple ETF, like the iShares US Energy ETF (IYE), they would have received 2.2 percent per year and matched the index’s volatility. A review of the table shows that a major part of the problem is the high expense ratios of the leveraged funds. While unlevered ETFs typically have low expense ratios, the inverse and ultra ETFs we reviewed had an average operating expense ratio of 1.3 percent. In addition, because the market for these ETFs is less liquid than it is for regular ETFs, trading costs (in the form of greater bid/offer spreads) are higher. Thus, the returns that real-world investors would have earned may have been even lower.

The results also show that higher daily volatility compounds into a larger problem when holding these funds for an extended period of time. Over longer holding periods, the greater the leverage employed, and the more volatile the market, the greater the negative impact on performance of a leveraged ETF.

The bottom line is that using leveraged or inverse funds as part of a broad portfolio strategy results in more volatility and may result in lower returns than just using a simple unlevered index ETF strategy. Long-term investors can put these products straight into the junk pile of products created by Wall Street that are meant to be sold, not bought.

LARRY SWEDROE is Chief Research Officer at Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of 17 books on investing, including Think, Act, and Invest Like Warren Buffett.

If you’re interested in reading more of his work, here are his other most recent articles for TEBI:

Factors to consider when choosing an index fund

The simple explanation for value’s underperformance

Are profesional investors prone to behavioural biases?

Are stock buybacks bad for shareholders?

Which factors guide investors’ decisions on asset allocation?

Just how efficient are equity markets?