It’s a real privilege to be able to welcome to our writing team here at The Evidence-Based Investor, the renowned investment writer LARRY SWEDROE. As well as writing weekly pieces for us, he’ll also be taking part in a regular podcast with Robin Powell; we’ll be telling you more about that in due course.

In his first article for TEBI, Larry discusses factor premiums and explains how, as an investor, framing a problem correctly is crucially important.

The value premium in the US (though not in international markets) has now been negative for more than a decade. According to data from Ken French’s data library, from 2007 through 2018 the annual average Fama-French U.S. value (HML) premium was -2.6 percent. Its underperformance has continued in 2019. The 12+ years of underperformance has led many investors planning for or already in retirement to question the advisability of adding exposure to value stocks beyond what is included in a total market fund. They frame the issue in the following way: “I don’t have 12 years to wait for a value or size — or any other factor — premium to show up. 12 years is just too long for me. That’s why I’m investing in a total market fund.”

The field of behavioural finance has taught us that how a question (or problem) is framed influences our answers. For example, Jason Zweig, in his wonderful book Your Money and Your Brain, showed the results of a study that asked more than 400 doctors whether they would prefer radiation or surgery if they became cancer patients themselves. Among the physicians who were informed that 10 percent would die from surgery, 50 percent said they would prefer radiation. Among those who were told that 90 percent would survive surgery, only 16 percent chose radiation. Clearly, the two choices are identical. Yet, highly intelligent, trained medical professionals allowed how the problem was framed to influence their decision. With that in mind, let’s reframe the question of whether one should diversify a total market portfolio by adding other unique sources of risk and return. Consider this version of the game we can call “Outfoxing the Box.”

Before playing the game, we need to make some basic assumptions. First, the evidence, such as from the annual SPIVA Scorecards, demonstrates that markets are highly, if not perfectly, efficient. Thus, market efficiency should be our core investment principle.

Second, if you believe that markets are efficient, it follows that you should also believe all risky asset should have similar risk-adjusted returns. Not similar returns, but similar risk-adjusted returns. For example, small stocks are riskier (and costlier to trade) than large stocks and thus have higher expected returns, but not higher risk-adjusted expected returns. At least from the viewpoint of classical finance theory, the same is true of value stocks (behavioralists make the case that the value premium is a result of mispricing).

Third, it follows that all risky assets are likely to experience long periods of underperformance. This must be true, or for long-term investors, there would be no risks.

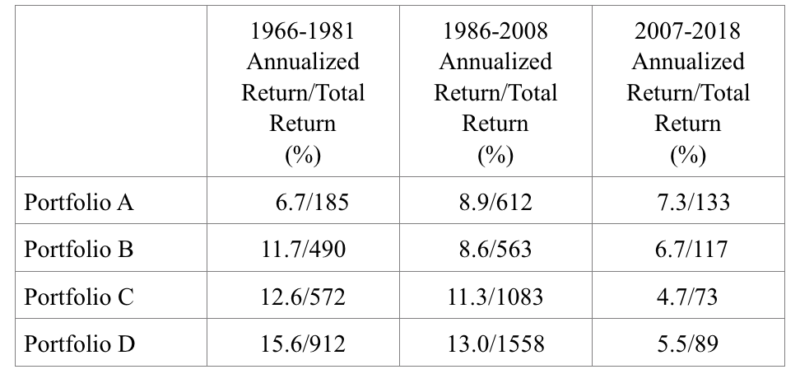

We now have the core beliefs we can use to determine the most appropriate investment strategy. With those in mind, you are told that you can invest in one of four boxes, each containing a passively managed portfolio, owning all the stocks in its defined universe. Because markets are efficient, each box has the same expected risk-adjusted return. The boxes are labeled A, B, C and D. To help you decide which box (investment strategy) to choose, the table below provides you with the following historical information, demonstrating that each of them endured long periods of relatively poor performance. Long periods of poor performance create greater risks for retirees. The reason is that sequence risk matters greatly in retirement because, once you begin withdrawals, losses cannot be recovered on assets spent.

Reviewing the table, you note that from 1966 through 1981, Portfolio A had by far the worst performance. Over that 16-year period, it even underperformed totally riskless one-month Treasury bills. Even worse, it provided a negative real return, as inflation rose by 7 percent per year. In terms of total return, A underperformed B by 305 percent, C by 387 percent and D by 727 percent.

We see a very different picture when we look at the 12-year period from 2007 through 2018, as A was the best performer. In terms of total returns, A outperformed B by 16 percent, C by 60 percent and D by 44 percent.

Turning to the period from 1986 through 2008, we find that in terms of total return, A outperformed B by 49 percent but underperformed C by 471 percent and D by 946 percent.

No matter which strategy you choose, you run the risk of it underperforming for a very long time by very wide margins. That said, it’s also worth noting that during the periods when A underperformed, its underperformance was much greater (in one case 8.9 percent per annum) than its outperformance was in the other periods (its largest outperformance was 2.6 percent per annum).

Investing in an uncertain world

Unfortunately, investors don’t have a crystal ball to tell us which of the four strategies will perform the best in the future. We only have particles of crystals, which are worthless for such purposes. So how do we choose, knowing that any one of them might do very poorly for a long time? Since no one knows which of the four will perform poorly in the next 10 or 20 years, choosing one could be viewed as making a bet, while choosing the mix is avoiding the bet, admitting you don’t know the future.

Since all risky assets have similar expected returns, the way to minimise the idiosyncratic risk of each of the strategies is to diversify across all of them, avoiding putting all of our risk eggs in one risk basket. You don’t have to decide between A, B, C and D. You can invest in all of them, outfoxing the box by refusing to play the game in that manner. Instead, create your own box E, diversifying your risks by investing some in each. In that way you reduce the risk of having all your eggs in the wrong basket while also eliminating the possibility of having them all in the “right” basket (which is known only in hindsight).

Now let’s reveal what’s behind the four strategies. A is the Fama/French U.S. Total Market Index. B is the Fama/French U.S. Small Cap Index. C is the Fama/French U.S. Value Research Index. And D is the Fama/French U.S. Small Value Research Index. (All the above table data is from Ken French’s website.)

Reframing the problem

Thinking that investing in more value stocks than are included in a total market fund is dangerous because you don’t have time to wait out a long period of underperformance frames the problem incorrectly. Yes, value stocks (and small stocks, small value stocks, emerging market stocks, momentum stocks and any risky asset) can experience long periods of underperformance. However, that is also true of the total U.S. market. In fact, according to data from Ken French’s website, it has underperformed totally riskless one-month Treasury bills over three periods of at least 12 years (1929-1943, 1966-1981 and 2000-2011). Importantly, during each of those periods, small, large value and small value stocks outperformed the total market, providing diversification benefits. In other words, you don’t have to choose from A, B, C and D. You can outfox the box and instead choose E, which diversifies across the different asset classes (and factors).

There’s yet another benefit from diversifying across other risk assets that have similar risk-adjusted expected returns.

Another benefit

Since small and value stocks have provided evidence of a premium (above the market) return that has been persistent across time and economic regimes, and pervasive around the globe, their higher expected returns (not higher risk-adjusted returns) allow you to hold less overall equity risk (since the equities you do hold have higher expected returns). That allows you to increase your exposure to safe bonds and term risk, further diversifying your sources of risk and reducing tail risk (and thus sequence risk). For those interested in learning more about this approach (often referred to as a “risk parity strategy”), I recommend reading the 2018 edition of Reducing the Risk of Black Swans: Using the Science of Investing to Capture Returns with Less Volatility.

Tracking variance

There’s one more important point we need to consider.

One of the attractions of investing in a total market fund (besides its low cost and high tax efficiency) is that its return should perfectly track the market’s return with no variance. On the other hand, a portfolio that diversifies across other sources of risk will, of course, experience tracking variance (not tracking error, which implies a mistake). While we know either choice will almost certainly experience a long period of underperformance, misery does love company, and failing conventionally (owning the market) is easier on the nerves than failing unconventionally. Thus, investors who are unwilling to fail unconventionally, even when the historical evidence and logic of diversification of sources of risk favors doing so, should stick with the total market approach. Otherwise, they are likely to lose discipline during the virtually inevitable periods of poor performance. In other words, sticking with a strategy is more important than choosing the optimal one you cannot stick with.

That said, John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, offered this advice on relative performance: “Relativity worked well for Einstein, but it has no place in investing.” Bogle warned about this because he believed that, for many investors, their satisfaction or unhappiness (and by extension, the discipline required to stick with a strategy) is determined to a great degree by the performance of their portfolio relative to some index (an index that shouldn’t be relevant to an investor who accepts the wisdom of diversification).

The next time you think about the question of diversifying the sources of your portfolio’s risk, be sure to consider the question from this standpoint: “Should I make a concentrated bet on market beta, ignoring other sources of risk with similar risk-adjusted returns?”

LARRY SWEDROE is Chief Research Officer at Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of 17 books on investing, including Think, Act, and Invest Like Warren Buffett.

Larry is a regular contributor to TEBI. Here are some of his other recent articles:

How interest rates influence risk taking

Do yield curve inversions tell us anything useful?

Talk of a passive bubble is just hot air

Are IPO stocks worth the risk?

Persistent outperformance remains very elusive