Robin writes:

We may think that the world is becoming more and more uniform, and that people’s lives everywhere are converging. Even if this is true, there are still parts of the world where lifestyles are very different to those in the English-speaking west. The values that underpin those lifestyles, and the wisdom those values are based on, are always worth exploring.

In the latest episode of our podcast, Second Lives, presented by JONATHAN HOLLOW, he speaks to an author who has been hugely successful at looking into the values and culture of centenarians and other long-lived people in rural Japan, then translating those values and lessons to people outside Japan.

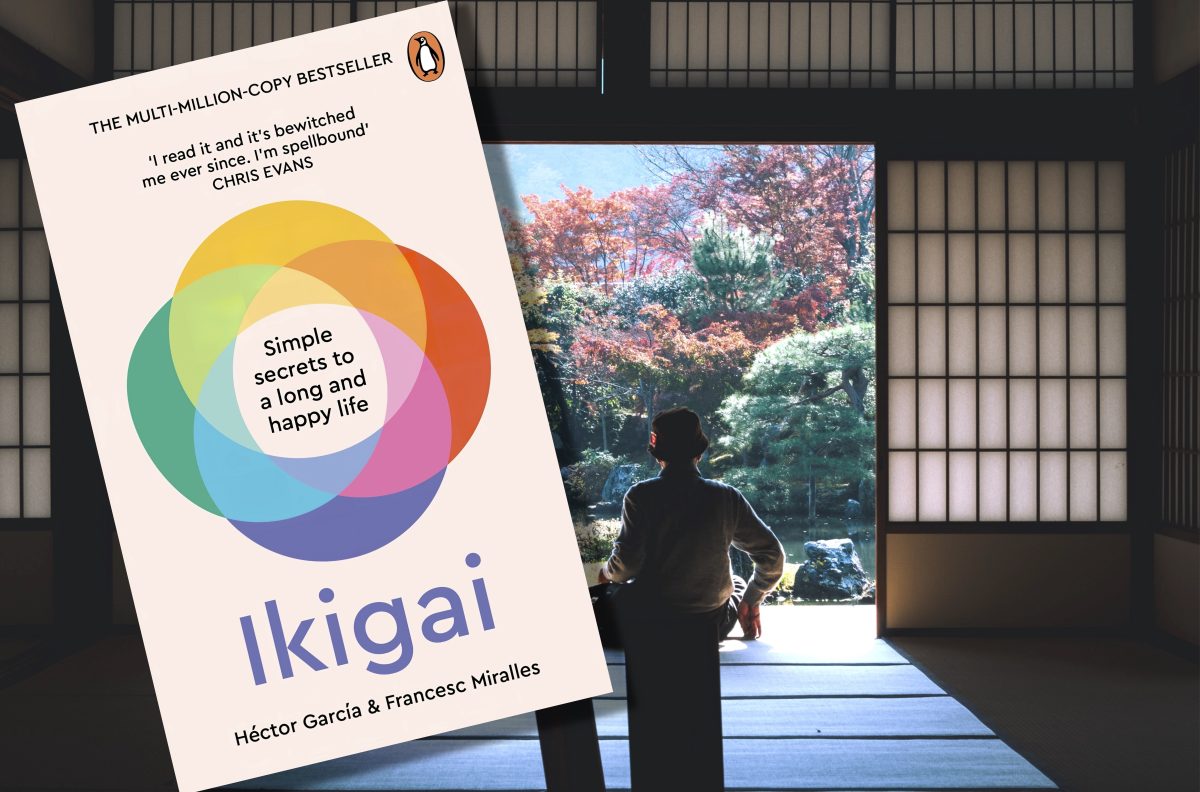

HÉCTOR GARCÍA wrote (with his co-author, Francesc Miralles) Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life. It’s about lessons in life, purpose and meaning from the longest-living people in Japan. It has sold millions of copies and has been translated into an astonishing 70 languages, including Japanese.

In Jonathan’s interview with Héctor, you will get a glimpse into the deep roots of Japanese culture, one that offers profound challenges to how each of us chooses to live all of their life — and especially the later stages of it.

And if you are wondering how to make a change in your own life, and find a fresh sense of direction, Héctor has a remarkably simple and practical suggestion for you. Listen to find out what it is.

Temple photo by Masaaki Komori on Unsplash

TEBI would like to thank the London-based financial planning firm Mulberry Bow for collaborating with us on this series.

As well as Spotify, you’ll find The TEBI Podcast on all the major podcast platforms, including Apple Podcasts, Listen Notes, PlayerFM and Podbean.

TRANSCRIPT

The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Please note, the copyright on this interview belongs to The Evidence-Based Investor. If you wish to quote any of it, you are required to attribute it to TEBI. We also request that you include a hyperlink to this article. We regularly monitor the internet for breaches of copyright, and any such infringements are dealt with appropriately.

Jonathan Hollow: Héctor, I like to think of Ikigai as, in many ways, an “anti-retirement book” …

Héctor García: I like that subtitle that you gave. Maybe we should change it. Or maybe we can create a new category in Amazon – “anti-retirement books”!

Jonathan Hollow: … does the Japanese language actually have a word for ‘retirement’?

Héctor García: Yeah, it has many words for retirement but, when you get into the nuance of what it really means, it feels – once you learn Japanese – it feels to me that the meaning is not as negative as the word “retirement”. So in Japanese, when you use the word “retirement”, it is more like you are transitioning to another phase in your life, in which maybe you were doing something, you were focused on a daily job, and now you’re going to be focused on your family. Or maybe you’re going to be focused on more relaxed work.

In Japan, you can work even after you are 65 or 70, you can work 20 hours per week and it’s perfectly legal. You can keep making money if you want – but most people, they retire in the sense that they stop working for a company, but they keep doing all the things they can focus on. Mainly focusing on hobbies: you become an artist or you focus on your family, on your community, things like that.

So the mindset is different. You are moving to another phase of your life.

For me, the word “retirement” in English – it feels like you are not going to be useful anymore to anyone. You are retired. And you use the word also for other things. When you retire old furniture, you don’t need it anymore. You are going to throw it away. So it has a bad connotation, I think; and I think that’s important.

I’m kind of almost a philosopher and I realise how important words are to our mindset and psychological wellbeing, and that’s maybe how I end up writing books where the title is just a word. Some people say, “Oh, that’s very simple. Just a word,” but the meaning that you can create from just a word: it can be very powerful – in a negative way or in a good way.

Jonathan Hollow: Let’s talk about “Ikigai”, the word that you used to title your bestselling book. It has a rich meaning. You’d struggle to translate it simply into other languages. How would you try to convey what Ikigai means?

Héctor García: You can translate ikigai simply, like “a reason for being”, or “your purpose in life”. It literally translates as “what is worthwhile doing” – so that can be different for each of us.

One question I get a lot is, can I have many ikigais, or can my ikigai change? And the answer is: yes for many people, and maybe for some other people, it’s not possible. It might be just one thing for you all your life, or – for most people – I think it changes depending on the phase of your life where you are. Maybe in your twenties, what makes your life worthwhile is something very different from what will make it worthwhile when you are in your fifties.

So the word “ikigai” compresses that. When you ask someone what is your purpose in your life, you can say just “what’s your ikigai?” I also tell parents – if you have your kids, maybe to put them in a better state of mind: instead of asking them “What do you want to be when you are older?”, you can ask them, “What is your ikigai?” And then that will make kids think more deeply. It’s not only about, “Oh, I want to be a doctor,” but maybe it’s about, “My ikigai is I want to learn how to cure people, so I will improve their lives.” So that changes the mindset and then maybe they will become a doctor or maybe they will become something else. Maybe they will start building new hospitals, for example.

Jonathan Hollow: A doctor is a role, whereas healing people is an activity.

Héctor García: Yes. We are also having a meaning crisis in society as a whole. Ikigai is about meaning, about giving meaning to your life. If you reduce this to a role – like I’m a teacher, I’m a doctor, I’m a dentist, I’m a software engineer – then that’s okay as a starter, but it might be if you identify only with that, that might not be enough to keep you going. So, it is better if you think in terms of what gives meaning to your life. Now you are a software engineer, and then later you become a lead software engineer, and later you are a leader of people – but your ikigai is building good services for users, for example.

Jonathan Hollow: I’m guessing from what you’re saying that ikigai is an everyday word in Japanese.

Héctor García: Yes. It is so everyday that it is kind of funny that, now our book has also been written, it was the first book about ikigai that was published. Now I think there are more than 50 books about ikigai. We are proud to say that we started the fire and it was translated to Japanese and Japanese people read the book, Ikigai, and they are surprised that there is a book just about this word. And some people criticise it, like they say: it’s pretentious. It is just a word! But I think as long as it is useful to people, I think we are doing a good thing.

Jonathan Hollow: You and Francesc, your co-author, didn’t take a theoretical approach to understanding this word. You went to the epicentre of healthy longevity in Japan, and you interviewed many supercentenarians. So I’d like to take a look at the places you went to – Okinawa and Ōgimi. What makes these two places so statistically remarkable?

Héctor García: Inside Japan the place with the longest living people is Okinawa and then, inside Okinawa, the village with the longest living people is this place called Ōgimi, and that makes this the longest living village in the world. A very special place.

And we went there; we always say that we are not scientists, we are more writers – and very curious writers. We would have ideas and write books about these ideas and then let those ideas be expanded by other people. Now, I know several people now in universities contacting us because they are doing PhDs based on Ikigai. So they’re really doing studies of people who retire and do absolutely nothing, and people who don’t really retire – they keep on doing their hobbies – and see if there is a correlation between having an illness that will end your life or having a very bad illness or not. And it is starting to be clear that there is evidence that retiring and doing absolutely nothing is really bad for you.

That’s the first thing we realised in Ōgimi: there was not really anyone really retired and doing nothing. Everyone was very active. Our taxi driver was more than 90 years old. We went to a birthday of three people who were, if I remember correctly, more than 90 years old. And they were dancing more than us! Than we were in our forties. So that was weird. They had more energy than us. It’s a very special place.

Jonathan Hollow: Can you build up a picture of these people and what they said about their ikigai?

Héctor García: Yes, that was one of the first questions that we asked them. The most striking thing was that they didn’t doubt when you asked them. They would answer you, “My ikigai is my family, my ikigai is taking care of my garden.” They like growing their own vegetables in Ōgimi. Everyone came up with an ikigai very fast. If you do the same experiment in a big city like, for example, here in Tokyo, it is not the same. People will have many doubts. Maybe they will come up with a more nuanced answer like, “I don’t really know what is my ikigai, but my work is this.” In Ōgimi, the answers were very clear.

I always tell a story about the lifestyle in the countryside in Japan, which is very different from Tokyo. Tokyo is a city that has the same, or very similar problems to the rest of the big cities in the modern world, where people are losing sight of the meaning in their lives. Their ikigai, basically. So on the cover of the book, we put the word “Japan”, but it’s a little bit more than Japan. It’s a book about the old countryside lifestyle of Japan and of that mindset.

Jonathan Hollow: And it sounds like the ikigai that these people gave you was quite humble, I suppose. Not highfalutin.

Héctor García: That’s also one of the key points. You don’t need to come up with something that is going to impress … you’re going to change the world, or things like that. Ōgimi is a very peaceful place. You don’t see many people with smartphones and things like that. So it is maybe easier for them to keep that lifestyle that they’re more connected with what they do, they like, and what they enjoy – which sounds very simple. But, when we get busy with life, we sometimes forget.

Jonathan Hollow: I want to build up a little bit of a picture of your book for listeners. It’s a very rounded portrait of successful longevity. It covers philosophy, social relationships, stress, diet, exercise, and also individual projects and passions. I think those last two are the most elusive. What would you say to somebody who is saying, “I’m fed up with my old way of life. How do I find a new reason for getting up every day for the next 40 or 50 years?”

Héctor García: We can say, if you are frustrated with your current lifestyle or whatever it is that is going on in your life; the good news is that it’s good that you are aware of that. Some people, they are not even aware of that, so it’s a good thing that you are here listening to us. That’s the first thing to realise.

Once you are aware of something – this is not only for a change of life, but changes of anything – having awareness (this also comes from Zen philosophy of the Japanese) – having awareness of things is the first step to saying – “Okay, do I want to make a change to this, or do I want to keep doing things the same way?” You can make a decision. Without having the information, you cannot even make the decision.

So that’s the good first news. I don’t believe in change that is going to happen immediately like a miracle. I’m not that type of person where I’m going to give you a pill and tomorrow your life will become … if you read my book or listen to my words … your life will change forever in an instant. I’m not that type of person.

And also for myself, when I have made changes in my life, it has been usually a very slow process. I usually take the strategy of trial and error.

A very actionable thing you can do in the next 15 days is: you can try writing at the end of the day.

You get a piece of paper. It can be a Post-It. I’m not going to ask you to write a diary every day. But you can write three things that you really enjoyed at the end of your day, and three things that you really, really disliked.

And write every day for 15 days. Even if it’s the same thing. In fact, that’s good. Maybe some days you will notice that you write the same thing. “I didn’t enjoy spending time with this person”, or “I really love doing this during this time.” After 15 days, you will see patterns and maybe you will see something very obvious, something you already knew, but seeing it in 15 small Post-Its maybe will make you take an action: like, okay, I really dislike this thing. I want to remove it from my life.

The idea is that you add more things that you enjoy to your life and remove things that you dislike in a slow way. So, if you do that over time, you will see big changes. If you do small changes on a daily basis over months and years, it will change the way you are now. And the way you will be in two, three years from now … it will be very different.

You can take the perspective of: “What is the worst that could happen?” When you look through that lens, the worst that can happen is … not that bad. Maybe if you are stuck in a job that you don’t like, maybe you are very fearful that maybe you will find a new job and it will be even worse. But the worst that can happen is that you change jobs and maybe later you have to change jobs again. That is nothing. You will become stronger in the process. That’s how I see change.

Jonathan Hollow: Another really important concept that you cover in your book is the act of entering flow state in your work or activity, and being able to shut out distractions. I was fascinated by some of the examples that you talked about from Japan where you observe people working on physically repetitive, minutely detailed tasks that we would probably consider quite boring. What have you learned from looking at these Japanese masters?

Héctor García: I learned that I might never be able to become a Japanese master! I’m a very patient person, but I realised that there is a completely next level of patience. Yeah, I think in the book I thought I was very impressed. I visited a factory of – how do you say, in English? Not pencils, but now the word comes in Japanese to my mind …

Jonathan Hollow: Was it for paint brushes?

Héctor García: Yeah, paintbrushes. That’s the word in English. And the way they have them all exactly the same size, it’s very, very detailed work. They have special employees who have been doing this for decades and it’s very difficult to replace those people. Only when they need to, they train them just to become that. So that’s a whole new level that maybe – if we have listeners who want to become artists – you can get inspired by them, and try to achieve their level.

For me, it serves as inspiration. For myself it’s about writing. I want to become a better writer. So for me, I have to be very patient. I have to choose the words in my books to become a better writer. So for each of us, we can find inspiration in the masters. And I think it’s not only true for the Japanese, but usually when you look at any very good artist – it doesn’t matter about their nationality – they are very, very patient and they can spend hours and hours every day for decades improving just a small thing in their technique. That’s how you make a genius, I think.

Jonathan Hollow: So we’ve talked about some of the physical activities that you looked at in the book. I want to talk about mental states now, and I want to start with stress, which seems to surround us like a fog in modern life. If people are thinking about a second life, do you think they should be aiming for one that tries to completely eliminate stress?

Héctor García: I see bad stress and good stress. Now, bad stress is the stress that is always with us – 24 hours – and it is sneaking into our minds, so we are always in a threatened state. We wake up, and we are already thinking, “Oh, it’s going to be a busy day. I have to do this, this, this, this,” and at the end of the day, you are still on your smartphone when you’re in bed and you are checking emails and you’re still thinking, “Oh, I didn’t have time to finish this.” And then you wake up in the morning, you cannot sleep. You wake up at night thinking, “I forgot this!” You wake up in the morning and, again, you are stressed all day. And then the weekend: and you’re stressed with your family and you’re always in a state of do more, do more, do more, do more … We have to blame this hustle culture, where you have to do more and more and more to be successful in life.

I don’t think that’s true. In fact, I’m realising it’s more about doing less, less and less. Like … almost do nothing except what is important and crucial for your life. If you enter the mindset of doing more and more and more, it becomes almost like an addiction. You need to do more and more things – yet you are not doing it because you enjoy it. It’s a stressful mechanism. That’s very bad stress.

Now, I think there is good stress that – when you are normally in a relaxed state – and you have something that is challenging, and you are looking forward to it – you will become stressed. I’m thinking now in terms of hormones. Your body will administer adrenaline and you will be excited for something and then you will do that, and at the end you will be tired and then, later, you relax. And that’s the way human beings are supposed to be operating. That’s how our biology is.

A very concrete example is, for example, talking with you. I was excited before coming here. So 30 minutes before I was, “Oh, I’m going to be on the Evidence-Based Investor podcast. I have to be ready!” So that makes me excited. That gives me a little bit of good stress. And I’m stressed.

When I finish, I will be tired and I say, now I want to relax and probably it will be eight at night, nine at night – I will disconnect all digital devices and I will relax. And that’s the way we are supposed to operate.

Jonathan Hollow: Let’s turn to negative emotions. You have some interesting things to say in the book. You contrast a Western approach, I suppose, which is to do with trying to eliminate negative emotions through rational processes in your mind. And I think you contrast that with a more Japanese way of acceptance.

Héctor García: You recognise a bad emotion and you look at it. You look at it and, at some point you’re like, “Okay, it will disappear, or it might not.” You just contemplate it. When you become angry about something, it is very interesting to analyse: why are you angry? And there are different levels – the first level is usually because this person said this rude thing to me. But then you can analyse … the second level is: why was it rude? Your ego has been attacked, or your pride has been attacked in a subtle way, maybe. You are being angry just because your sense of pride has been attacked. It is a very deep emotion, but it has no connection with residual reality. Once you start looking at things like this, it is really interesting.

Jonathan Hollow: Another concept that you cover in the book is the “moai”, which is something I understand to be a Japanese model for collective support and resilience. Can you build up a picture of it for us?

Héctor García: Moai is a word used for communities of people that don’t really need to have a common purpose, but the purpose of it is just … to be together. They put in money. Every month or every certain time, they collect the money. And with that money they do activities. And, depending on what they like, it might be doing karaoke together or having parties together, maybe dancing. The party I mentioned before – the three birthdays with the old people – it was a moai that paid for everything. And other times, when someone in the moai is going through bad times, the money from everyone might be used to help them. For example, if there is a typhoon and it destroys one house, the moai – maybe the whole neighbourhood is in the same moai and they have collected some thousands of dollars over the years – they will use it to repair the house of the person who cannot rebuild it.

So that’s the purpose of moai, to have a sense of security. Whatever happens, you will have a second family. And this is very useful in villages where there are many old people, which is a problem in Japan. There are not enough young people to support older people (and I think this is something that is going to start happening also in other developed countries in the world). Feeling supported is very important. When you are old, you need a community around you so you feel that you have someone to help you at any time, or to be with you sometimes. Moai is just about getting together and having a cup of tea together.

Jonathan Hollow: And what kind of scale are these on?

Héctor García: The ones I know from Ōgimi, it was between 20 and 50 people. So keeping small is easier. But they share places – the city hall will have community centres. Three or four. And then they will say, “Okay, on Wednesdays we will use this one for this moai,” or maybe they will gather in a restaurant and each moai has a head – that’s also very Japanese. It’s like a neighbourhood, or an extra layer of a neighbours’ organisation.

Jonathan Hollow: It seems to me that living in Japan has changed you in many ways, and at one level you’ve written a multi-million bestseller, which wouldn’t have happened without your deep engagement with Japanese culture. But I feel like the change has been more profound than that.

Héctor García: You are becoming my psychologist! I don’t know, this is a very good question.

In fact, can you describe yourself 20 years ago? It’s so difficult, right? I know that I’m a big diarist – I’ve been writing a diary since I was 14, 15 years old, and I keep that habit; and sometimes I go back and read my diary. And I know it feels very, very weird. It’s like reading something that was written by someone else.

So I feel that it is true what you said. I am a totally different person, but some themes are the same. There is some kernel in me that stays the same. He is the same Hector, and maybe Japan made me more patient. That’s one thing. It has made me more perseverant.

For me, it’s very difficult to separate Japan with getting older. I’ve changed my perspective. A long time ago I thought being stubborn was a bad thing. Now I think being stubborn for the right things is a good thing. So I think I have become more stubborn. So maybe I’m becoming more stubborn, more patient, more perseverant. On what I know for sure is my Ikigai – or my things that I really like doing – I kept persevering. 20 years ago, Héctor might have just given up and tried something more shiny.

Jonathan Hollow: Do you feel that you’re more at home in Japanese culture than your Spanish culture?

Héctor García: I don’t feel at home anywhere. That has become a weird thing for me. I think I’m a citizen of the world. But when I’m here in Japan, there are some parts of my personality that get activated. I don’t know how to explain it. I think there are studies about, when you go into a culture, human beings – we change. Even depending on the context, if you’re with your family, if you are alone with your partner, if you’re with your friends – we change a little bit, as humans. If you’re in a different culture, you will change. When I go back to Spain after 15 days, there are things inside me … the old Spanish Héctor, he gets activated! I start speaking more loudly and saying things more. In Japan, it’s more about speaking more quietly, and things like that.

Jonathan Hollow: I’d like to ask about planning, which is a recurring theme of this series. Did you plan the last ten years of your life?

Héctor García: No, absolutely not. I usually think more of what I can achieve in ten years, than what I can achieve in one year, so that’s how I think.

Now I think, “Okay, in the next ten years I want to write five more books.” That’s my general mindset. I don’t think – 2023, I have to publish one book – because probably I won’t. I already know I’m set, I need more than one year to write a good book. But, in ten years, writing five books, it’s a good goal. Also with experience in life, you get a better sense of how to make realistic plans. Before I would say, “Okay, this year, I want to do like these 30 things.” And you realise that those 30 things, it will take you a decade to do those! Not one year. If you try to set 100 goals and you don’t achieve any of them, (or just one), it’s better to just set one or two and then go for it.

I like more having a compass than having a map. Or having a map that is a little bit less precise: you want to go to this island, this island and this island, but maybe while you are heading north, you want to change a little bit and visit this other island and this other one and this other one … So I like making changes along the way and having an overall plan. I guess it’s a good thing because it will keep you following the same star or the same compass.

Jonathan Hollow: Finally, I’d like to just ask you to remind people about yours (and Francesc’s) book, Ikigai.

Héctor García: At the beginning of the book, I say that I dedicate this book to my brother who told me: “I don’t know what to do with my life, brother – help me.”

I think it will help you. Either way, if you don’t know what to do with your life: it will help you. And I don’t give any promises. The only promise I give you is that it will help you to start you on your path. The rest is your responsibility.

BUY ROBIN AND JONATHAN’S BOOK

How to Fund the Life You Want by TEBI founder Robin Powell and Jonathan Hollow is published by Bloomsbury. It was unanimously adjudged Work and Life Book of the Year at the Business Book Awards 2023. Although primarily aimed at a UK audience, it contains valuable lessons for readers everywhere.

Buy the book here on Amazon, or, if you prefer, here on bookshop.org.

ALSO IN THIS SERIES

LISA GRANIK MW on a new life in wine, looking back on law, Stalin and a long relationship with the Caucasian country of Georgia

BRIAN PORTNOY on how to master the “evolutionary two-step” that keeps us fearing (and hoping) throughout our money lives

ALEX DAVIS on her journey from company director to Latin scholar

ANDREW HALLAM on learning from philanthropists, investors — and people everywhere — about what makes life worth living

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIII