By LARRY SWEDROE

The outstanding performance of the Yale Endowment Fund, managed by legendary investor David Swensen, led many public pension plans and endowments to try to replicate its performance by increasing their exposures to alternative investments such as private equity, private real estate and hedge funds.

Richard Ennis, author of the study Institutional Investment Strategy and Manager Choice: A Critique, published in the special Fund Manager Selection 2020 issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management, analyzed the investment results of these institutional funds, shedding light on their costs and diversification patterns. He created two composites of returns: one for public pension funds and the other for educational endowment funds. The public fund composite is an equal-weighted average of the returns, net of expenses, of 46 large public pension funds.

Public fund data was obtained from the Pension Plan Data database, maintained by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. For educational endowment funds, Ennis used data provided in the NACUBO survey for endowments greater than $1 billion in value. His database included approximately 100 institutions. Fund returns are equal weighted and net of expenses.

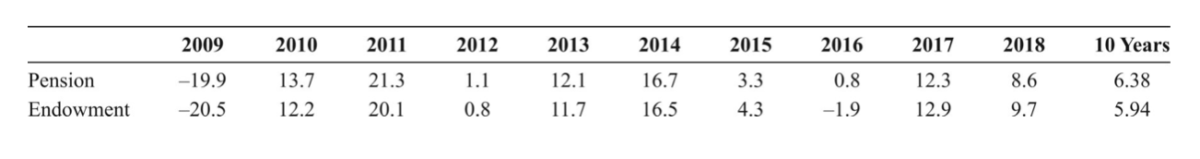

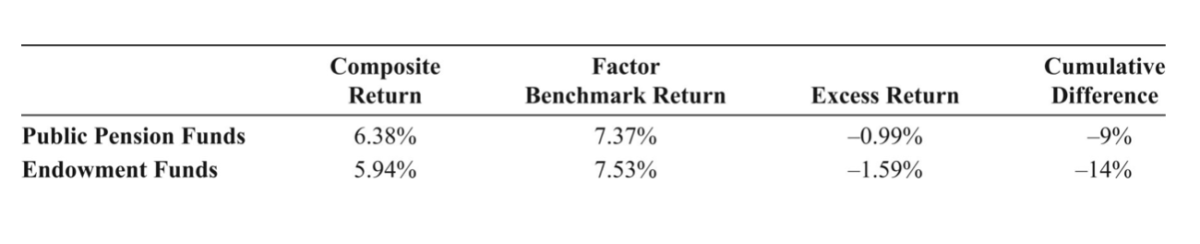

The following table shows returns of the two composite indexes of the ten years ending in 2018.

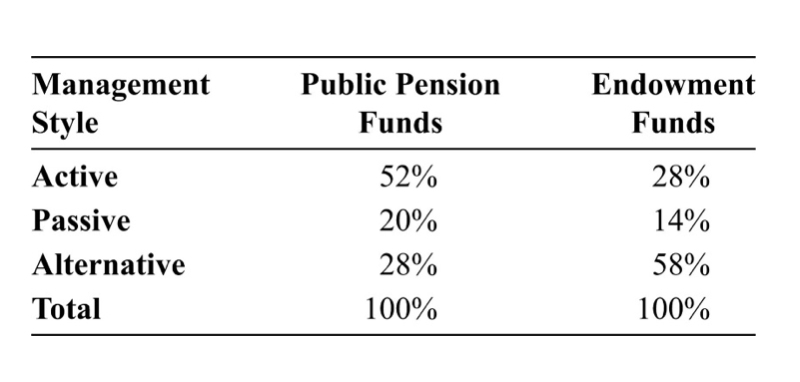

The next table shows the asset allocations of the pension and endowment funds.

Explaining performance

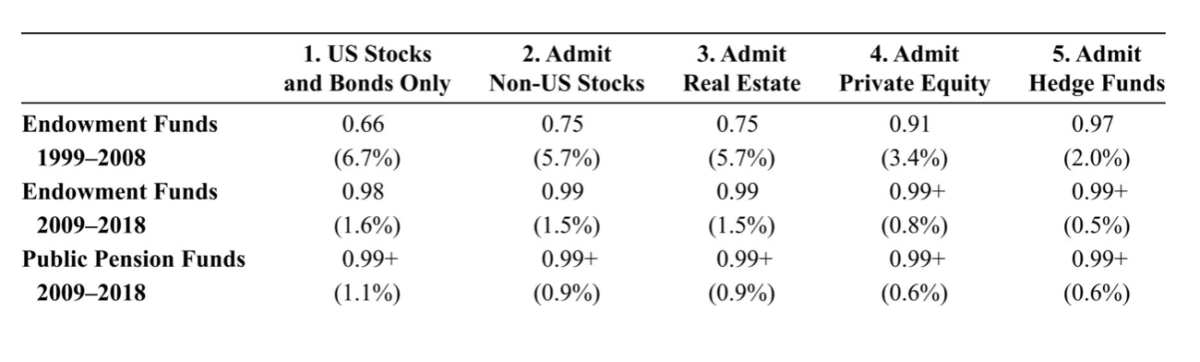

Ennis then identified six asset-class indexes that might help explain the variation in performance of the two groups: the Russell 3000 Index, the Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index, the MSCI All-Country World ex-US Index, the Cambridge Associates Private Equity Index, the Cambridge Associates Real Estate Index and the HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index. The following table shows the R-squared values (which demonstrate explanatory power) and the tracking errors.

There are a few important takeaways. First, note how adding additional investments improves the explanatory power of the model. Second, over the last ten years using only publicly available stocks and bonds, we have R-squared values of 0.99 and tracking errors of just 1.5 percent and 0.9 percent. Including all categories reduces the tracking error to about 0.5 percent — the benchmark indexes have great explanatory power. Despite the alleged diversification benefits, alternatives had a negligible impact on endowment diversification over the ten years ending in 2018.

Benchmarking performance

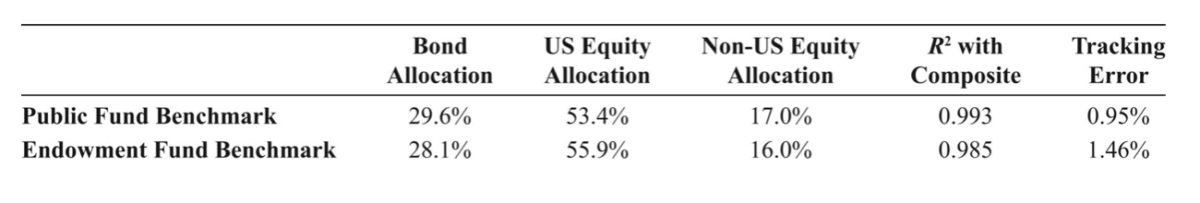

Ennis then benchmarked the performance of the public pension funds and the educational endowments using publicly available indexes. The table below shows the benchmarks, the R-squared values and the tracking variance.

Having established the benchmarks, Ennis analyzed their performance.

Ennis found that the public pension plans underperformed their benchmark return by 0.99 percent and the endowments underperformed by 1.59 percent.

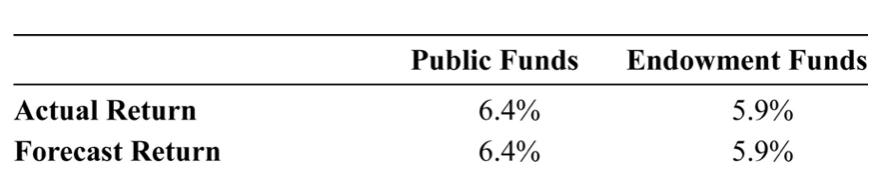

As an out-of-sample test, Ennis used his model to forecast returns for the year 2019 and compared his forecast to actual returns. The table below shows the results.

These findings led Ennis to conclude that “public securities markets have become the essential drivers of institutional portfolio return”.

Costs matter

Ennis then turned his attention to estimating costs. He estimated the typical cost, including transaction costs, of institutional stock-and-bond-only investments at approximately 0.54 percent of asset value. He used the results of the study “Practical Applications of Alternative Asset Fees, Returns and Volatility of State Pension Funds: A Case Study of the New Jersey Pension Fund” by Jeff Hooke, Carol Park and Ken Yook, published in the March 2020 issue of The Journal of Alternative Investments, to estimate the costs of the alternatives — 2.48 percent. Ennis estimated that the public pension plans had a weighted-average cost of 0.98 percent and the endowments had a weighted-average cost of 1.67 percent.

Note that these estimated average costs are very similar to the composites’ respective margins of underperformance: 0.99% and 1.59% per year relative to passive investments. Of course, benchmark indexes have no costs. However, publicly available stock and bond strategies in these broad indexes have very low implementation costs. For example, from 2011 through 2019, Vanguard’s 500 Index ETF (VOO) returned 13.33 percent, underperforming its benchmark index by just six basis points.

Odds of outperformance

Ennis found that of the 46 public pension plans, just one generated statistically significant alpha, compared to the 17 that generated statistically significant negative alphas. He also calculated that “the likelihood of underperforming over a decade is 0.98 — a virtual certainty.”

It is evidence such as this that led Charles Ellis to declare active investing a loser’s game, one that is possible to win but the odds of doing so are so poor it isn’t prudent to try.

Private real estate

Ennis then turned his lens to the performance of private real estate investments.

Citing the Nareit study Updated 20-Year CEM Benchmarking Study Highlights REIT Performance Versus Private Real Estate, he showed that private-market real estate underperformed publicly listed real estate investment trusts (REITs) by 2.8 per year between 1998 and 2017. He also cited the study Another Look at Private Real Estate Returns by Strategy, published in the 2019 Real Estate Special Issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management, which determined that non-core real estate significantly underperformed between 2000 and 2017.

The authors calculated the annual alpha of “opportunistic” funds at 2.85 percent and that of “value-added” at -3.46 percent relative to core funds.” They concluded: “The largest contributor to the poor showing of non-core investments was their cost, which they put at 3% to 4% per year of the equity portion of investment value.”

Private equity

Summarising the research on private equity performance, Ennis reported the following:

— private equity returns resemble those of domestic small-cap value stocks without a return premium; the cost of private equity investing approximates 6 percent per year of invested capital

— the excess return for buyout funds turned decidedly negative in the mid-2000s

— public market equivalent values for private equity declined from 1.2 to 0.8; and U.S. buyout funds achieved an average annual excess return of -2.7 percent to -3.2 percent between 2006 and 2014.

Hedge funds

Summarising the research, Ennis reported that over the last decade hedge fund alpha had turned negative. In addition, their returns “have become more highly correlated with traditional active-stock management, making the strategy less attractive in terms of its diversification potential”.

Summary

It’s clear that the addition of alternative investments such as private real estate, private equity and hedge funds has negatively impacted the returns of both public pension plans and educational endowments, without providing any diversification benefits.

It’s also clear they would be better served by limiting investments to publicly available securities.

Ennis summarised his thoughts: “The most any investor need pay for its passive portfolio is 5 bps, the prevailing cost of a blend of retail mutual funds. Large institutions can get it for a single basis point or less. It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of such an advantage in a world in which the competition is routinely paying 1.0% to 1.7% for the management of diversified portfolios in highly competitive markets — portfolios likely to earn single-digit returns for the foreseeable future.”

LARRY SWEDROE is Chief Research Officer at Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of numerous books on investing.

Want to read more of his work? Here are his most recent articles published on TEBI:

DC pensions should switch to passive funds — study

Have we seen the death of value?

Can you trust bond fund classification?

Is the rise of indexing bad for corporate governance?

Is it really stocks for the long run?

The illusion of alpha in active bond management

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXX