By NICOLAS RABENER

Summary

- There is a negative relationship between ageing populations and stock valuations

- Given that most developed markets are ageing, this creates structural headwinds for equities

- The massive future population declines require investors to rethink traditional asset allocation

Introduction

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.” – Friedrich von Hayek

“The use of mathematics has brought rigour to economics. Unfortunately, it has also brought mortis.” – attributed to Richard Heilbroner

In finance, everyone loves to make fun of economists. Even economists.

Perhaps the field is simply too complex for our simian brains to grasp: After all, the variables — GDP growth and interest rates, for example — are all interrelated, which makes it difficult to wrap our minds around them. At best, we create a mental map of positive and negative feedback loops. At worst, we develop something like a circular reference in Excel that may cause the spreadsheet to crash.

But sometimes economists do do obviously illogical and silly things. For example, Haruhiko Kuroda, the governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), has been buying up stocks, bonds, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) to counter what is fundamentally a demographic problem. In his defense, he is not the first BOJ governor to pursue such a course, and he only has monetary power at his disposal. But that power might be put to better use attracting the millions of immigrants who are needed to help Japan avoid eventual demographic collapse.

The headwinds are fierce: Japan’s population is expected to decline by 40% between 2020 and 2100, falling from 126 million to 75 million, according to data from the United Nations. Losing 50 million people while stuffing money in the pockets of those remaining won’t stem the tide: It’s more like giving bailing buckets to the passengers on the Titanic.

Unfortunately, Japan is a harbinger of what’s to come across much of the world. And while fewer people may be good for the environment, it is terrible for civilisation. Economic growth hinges on an expanding population. And the fabric that holds society together is always torn when the economy unravels.

This trend is also terrible for investors: Old people tend not to buy stocks.

So what exactly is the relationship between stock markets and population growth? Why are demographic trends so critical for equity returns?

What drives stick returns?

Simply stated, companies require economic growth to prosper, and gains in productivity and the working-age population are what drives that growth. We haven’t found a way to stop the ageing process, so an expanding population is required to replenish and expand the number of workers who contribute to the economy. If that working-age cohort is shrinking, stagnation may set in and firms will have a harder time growing their revenues and earnings. As a consequence, their valuations will decline since they depend on expected growth.

But there is more to this equation: Every transaction has a buyer and a seller. The young and middle-aged tend to buy more stocks: They have a longer investment time horizon and thus more capacity for the risk inherent in equities. In contrast, the elderly are net sellers as they de-risk their portfolios by moving from stocks to bonds. So, as the population ages, who will be left to buy stocks?

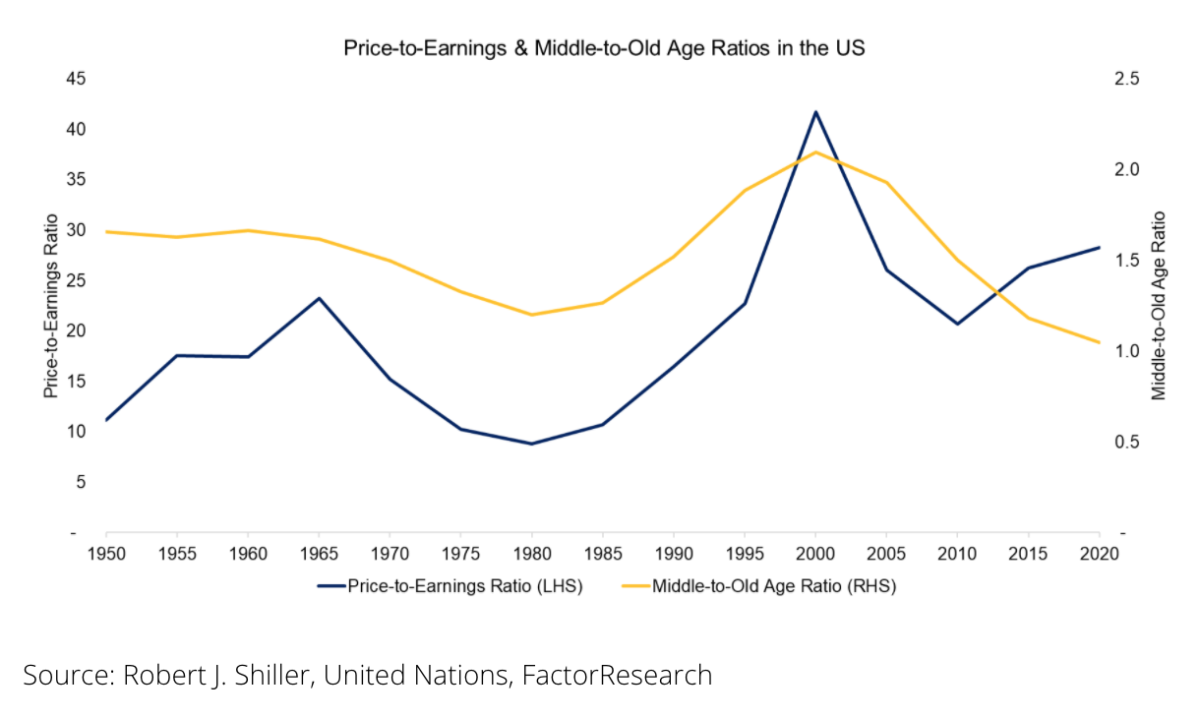

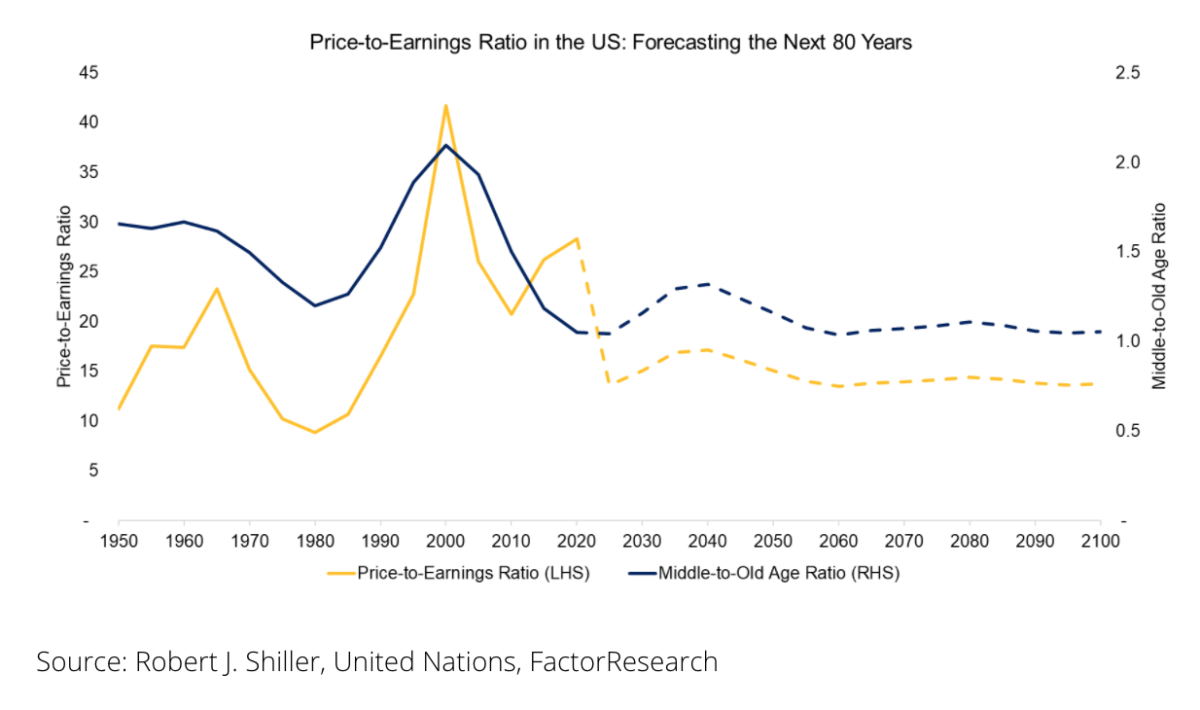

One way to visualise the impact of population changes is to calculate the middle-to-old-age and price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. Zheng Liu and Mark P. Spiegel of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco demonstrated this in Boomer Retirement: Headwinds for U.S. Equity Markets?

Their approach shows that the valuation of US stocks as measured by the cyclically-adjusted P/E (CAPE) ratio between 1950 and 2020 was largely driven by population changes. When the ratio of middle-aged people, or those between 40- and 49-years old, increased relative to the elderly, or those between 60 and 69, stock valuations rose. In turn, the higher the valuation, the higher the stock returns.

This would also help explain the tech bubble at the turn of the millennium, as the middle-aged grew faster than the elderly cohort and demand for stocks outpaced supply.

Global population forecasts

If population growth contributes to economic prosperity and stock valuations, United Nations (UN) population forecasts offer a glimpse of the future.

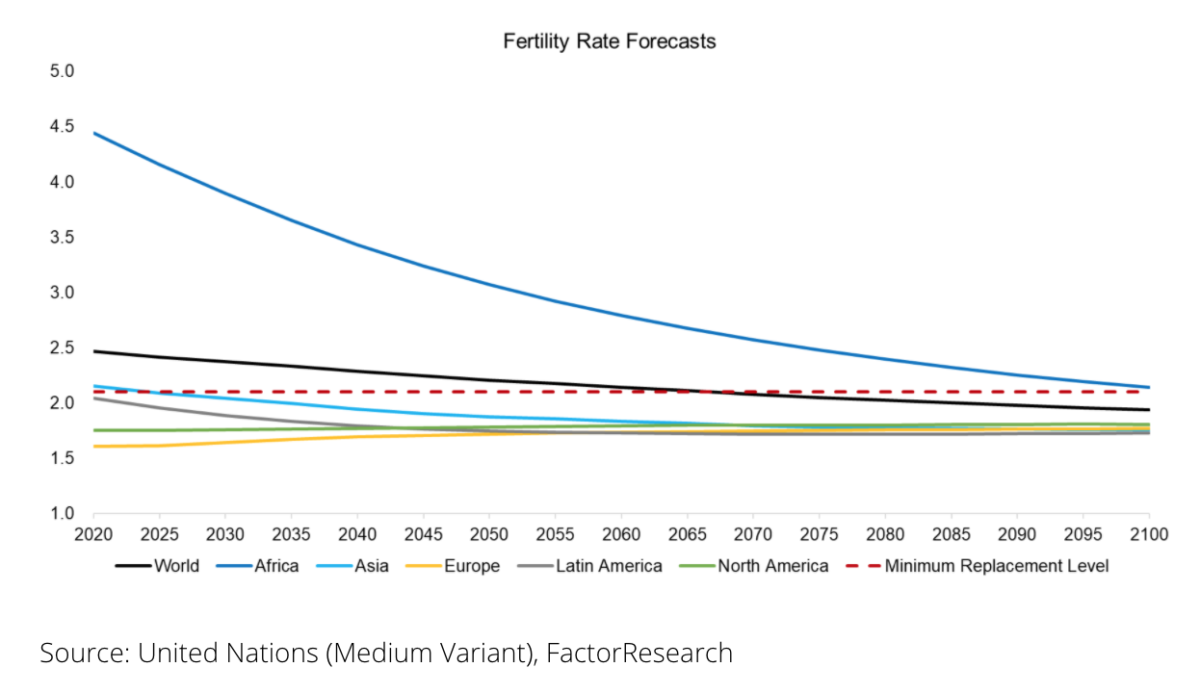

A fertility rate of 2.1 – each woman bearing 2.1. children on average – is considered the replacement rate, or what’s required to maintain the current population level.

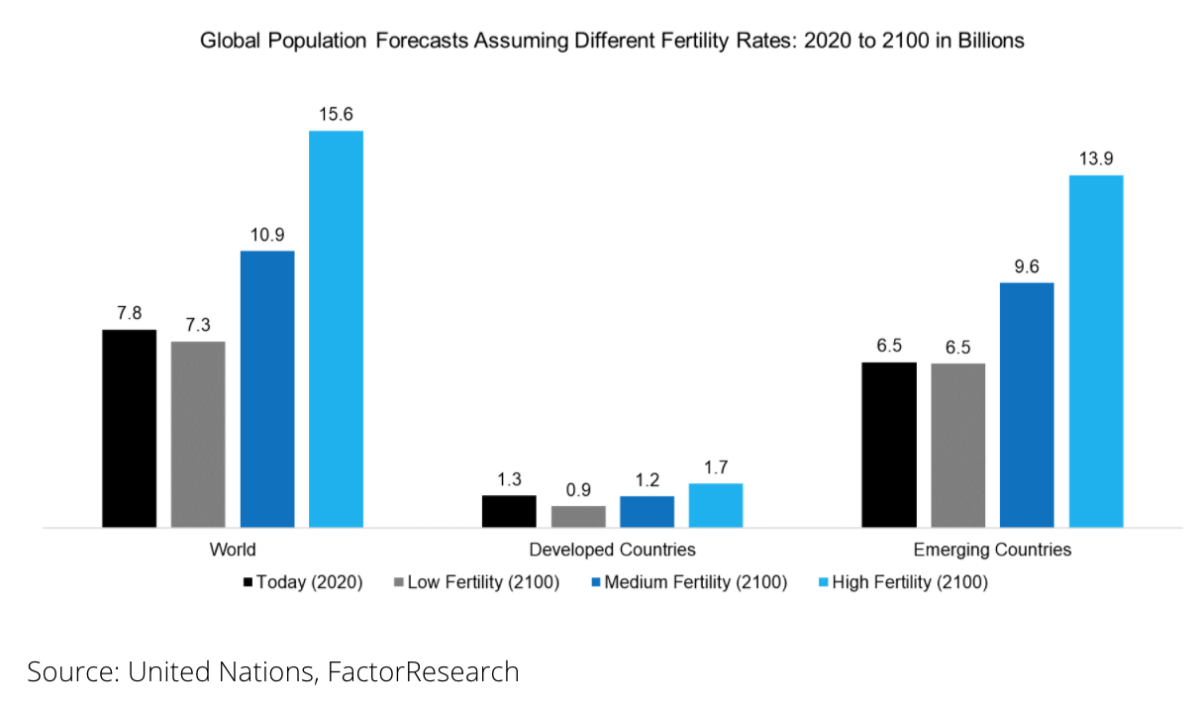

Today’s global population is 7.8 billion and is expected to grow by 40%, to 10.9 billion, by 2100. Of course, this outcome depends on which of the potential fertility rate scenarios forecast by the UN materialises. The populations of developed nations are only predicted to grow amid a high fertility rate environment. Failing that, growth is expected to be confined to emerging markets.

In the UN’s medium fertility forecast, Africa is the only region that is anticipated to exceed the replacement threshold over the next 80 years with the rate declining over time.

Countries with biggest population growths & declines

If an expanding population is critical to global economic growth and stock returns, with the world population expected to grow over the next 80 years, why is the outlook so dire?

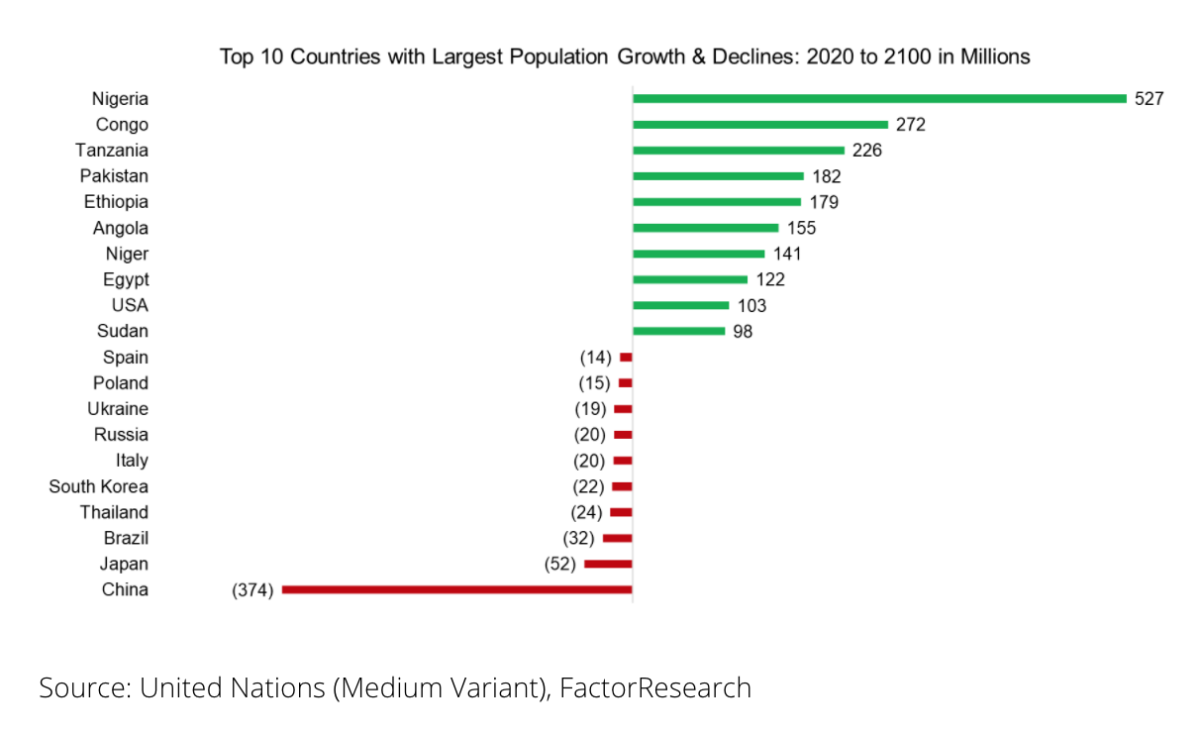

It comes down to how that growth is distributed. The only developed nation among the top ten in expected population growth is the United States. Otherwise, the only non-African nation is Pakistan.

Perhaps this century will belong to Africa and the continent’s emerging economies will evolve into developed ones. Unfortunately, history suggests this is not altogether likely. Of the world’s most advanced nations in 1900, 90% were still among the most economically developed 100 years later, according to research from Jay Ritter. Japan and South Korea moved from poor to rich and Argentina went from rich to poor, but otherwise the ranks of the developing and developed remained largely static.

And Africa has struggled to realise its potential. None of its 54 nations has made a leap like South Korea, which was poorer than many African states in the 1950s, but developed into an industrial powerhouse. Offering cheap labour is a classic development model, but that hasn’t worked in Africa.

Further dampening the outlook, fertility rate estimates are also more likely to be over- than understated. A stalled economy can quickly turn a rapidly expanding population into a declining one. For example, Iran’s fertility rate dropped from 5.6 between 1985 and 1990 to below 2.0 in less than two decades.

In contrast, fertility rates have not increased dramatically anywhere. Nor are they expected to. So population declines are more realistic than increases.

In such wealthy countries as Italy and Spain, the forecasts are especially stark. They are expected to lose 34% and 29% of their populations, respectively. The reverberations for the global economy will be severe as demographic decline sets in throughout many of the world’s wealthiest nations. Shrinking populations also make governing more difficult as public services like education and health care become more expensive.

Given these forecasts and the relationship between population dynamics and stock valuations, what is the outlook for markets in the United States? Unlike much of the world, the United States is expected to grow its population in the current century, but that population will be older on average.

Naturally, the valuations-to-population interplay is not a linear relationship and currently the CAPE ratio is well above its historical average and isn’t where it should be based on population dynamics. But as more US workers retire, they will swap equities for bonds, which does not bode well for the long-term demand for stocks. Every seller needs a buyer.

Further thoughts

These demographic trends have both good and bad news for investors.

Fortunately, most of the dramatic population declines are expected after 2050. Before that, only Japan is affected significantly. Perhaps it’s finally time to short Japanese government bonds?

Otherwise, these forecasts make a strong case for not only selling stocks for the long-term, but also selling all asset classes that are bets on economic growth. That means bonds, real estate, and private equity.

This requires investors to evaluate traditional asset allocation frameworks and consider strategies that are less dependent on a healthy global economy and an expanding population. That means anti-fragile portfolio strategies and securities that are truly uncorrelated to traditional asset classes or, even better, benefit from increased economic and financial volatility.

Like passengers on the sinking Titanic, investors have no place to hide and no safe harbour from which to wait this out.

NICOLAS RABENER is the managing director of FactorResearch, which provides quantitative solutions for factor investing.

Also by Nicolas Rabener:

Is the variance risk premium worth it?

Are tactical ETFs worth using?

Did smart beta fixed-income ETFs pass the COVID test?

How did different risk factors perform in Q1?

Why you should avoid thematic funds

Here are some other recent TEBI posts you may have missed:

There is such a thing as too much choice

When even the best are unlikely to win

No one sees their own blind spots

FIND AN ADVISER

Are you looking for an evidence-based financial adviser? We my be able to help you. Just give us your name and email address and we’ll email you a brief questionnaire to help us identify a suitable candidate.