By NICOLAS RABENER

Summary

- Harvesting the variance risk premium has a sound theoretical foundation

- However, actual investment products have generated poor returns

- Furthermore, they are correlated to equities, providing few diversification benefits

Introduction

Investing is akin to fighting in a never-ending war. There are long periods of peace and prosperity, but investors are frequently drawn into short-term combat, extended battles, and multi-year wars. And the cycle repeats over and over.

For some of the foot soldiers, the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 represented the first time in the trenches while many of their captains are still scarred by the global financial crisis of 2008. Experienced majors painfully recall the tech bubble implosion in 2000 and a few select generals lived through the sudden stock market crash in 1987 at the start of their careers.

However, even the bravest soldiers and most experienced generals get tired of intense warfare. The COVID-19 crisis represents the third major stock market crash in a mere 20 years. Given this, investors can not be blamed for trying to mitigate potential damage to their portfolios by diversifying into alternative asset classes and strategies with unproven live track records.

Currently, asset managers pitching new and unique weapons for the investor’s arsenal are finding an especially receptive audience. One of the more esoteric alternative strategies is harvesting the variance risk premium (“VRP”), which one firm has been marketing as the following:

“Product XYZ opens up the risk premium of volatility to investors using a short volatility strategy. The return drivers of this strategy differ from those of traditional asset classes. Adding volatility strategies to existing portfolios thus enables positive diversification effects.”

Naturally, these are highly attractive attributes for asset allocation. However, many highly hyped weapons have failed investors in previous wars, cautioning the more experienced investors on strategies that sound too good to be true.

In this short research note, we will explore the variance risk premium strategy as a means of diversifying traditional equity-bond portfolios.

What is the variance risk premium?

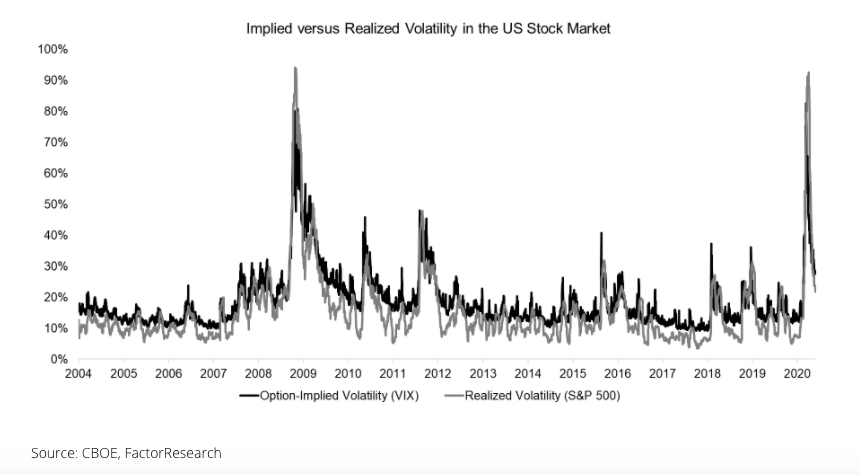

The variance risk premium represents the difference between option-implied and realised volatility, which is positive on average and has been observed in equities, as well as across asset classes.

The most common explanation for this premium is that investors accept to pay a premium for hedging themselves via options against market downturns. Effectively, the VRP represents the profits of an insurance business.

The spread between option-implied and realised volatility in the US stock market was slightly above 3% on average in the period from 2004 to 2020. However, although the premium was positive over time, it became negative when markets crash like in 2008 or 2020.

Quantifying diversification benefits

Constructing a portfolio for harvesting the variance risk premium is primarily done via variance swaps or by selling options on indices like the S&P 500. Although many investment banks offer variance swaps to institutional investors, there are few indices or products in the market that are accessible by all investors.

In this analysis, we focus exclusively on VRP mutual funds in the US and Europe, which results in a limited universe and should be considered when reviewing the results. We also include an index from Barclays that can be used to benchmark these products.

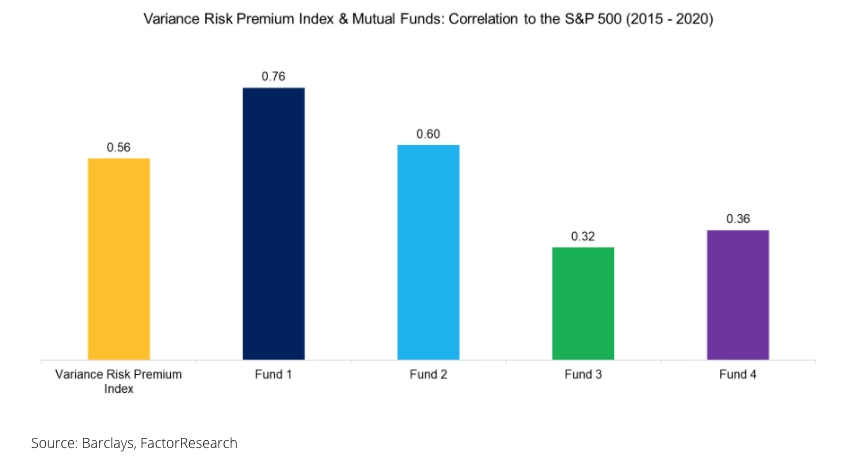

Asset managers frequently market the variance risk premium strategy as being uncorrelated to equities and make the case for adding such products to a traditional equity-bond portfolio for diversification. The correlations of the VRP index and mutual funds to the S&P 500 were moderate between 2015 and 2020. It is worth highlighting that all mutual funds focus on equities, except for Fund 3, which harvests the variance risk premium across asset classes and explains why that fund has had the lowest correlation.

Variance risk premium index versus equities

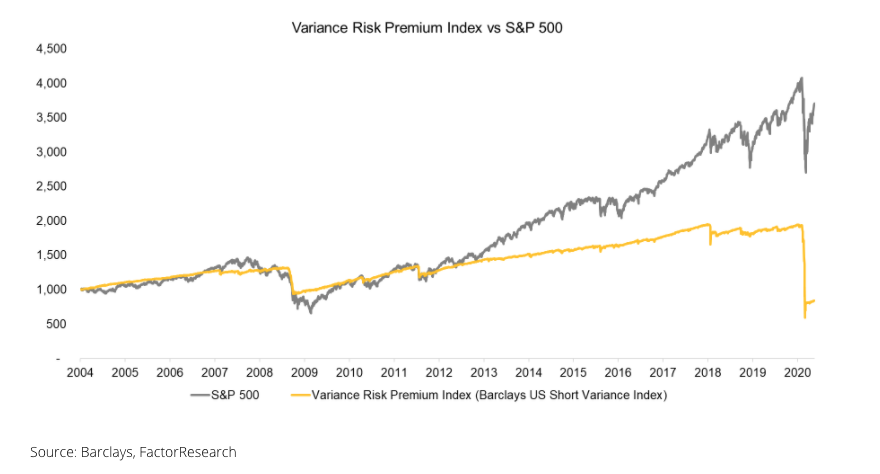

Given the moderate correlation to equities, one might be inclined to think that variance risk premium strategies might indeed be attractive for diversification. Next, we contrast the performance of the benchmark index versus the S&P 500. We see that while in the early part of the sample returns were almost identical, however recently they diverged quite a bit, in a manner that does not scream truly uncorrelated strategies.

The VRP index performance between 2004 and 2013 was more attractive than that of the S&P 500 as the total return was identical, but was achieved with lower volatility, therefore offering higher risk-adjusted returns. However, the performance before 2013 is based on backtesting as the index was launched in 2013, where the live performance thereafter was much less attractive. The difference in performance was especially pronounced in the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, where the S&P 500 almost recovered all losses, compared with a much more muted recovery for the variance premium index.

The VRP index showcases why most investors distrust backtesting: the simulated returns are the equivalent of wine-tasting in Sonoma Valley on a sunny day, while the realised returns post-launch are like the hangover after a massive college party with cheap booze.

Variance risk premium mutual funds versus S&P 500

Although the performance of the VRP index was poor, perhaps that is due to its systematic design. It also might be that sophisticated active management is required given the complexity of dealing with swaps and options.

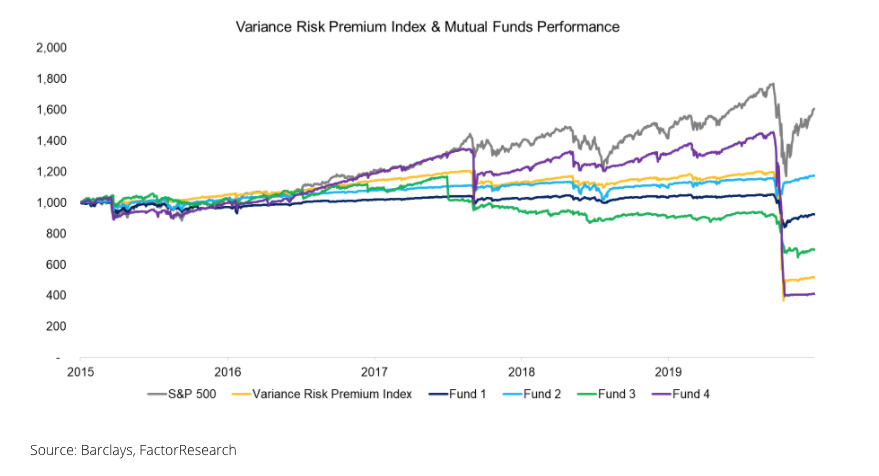

However, comparing the performance of the four mutual funds analysed here, some of which invest on a discretionary basis, does not suggest vastly superior portfolio construction. All seem like watered-down versions of the S&P 500, albeit with significantly worse performance in crisis times. The period between 2015 and 2020 comprises a bull market and stock market crash, and in neither environment did VRP strategies outperform.

Harvesting the variance risk premium across asset classes seems to have been even more challenging than in equities as Fund 3, which invests cross-asset, was already struggling to generate positive returns since mid-2017.

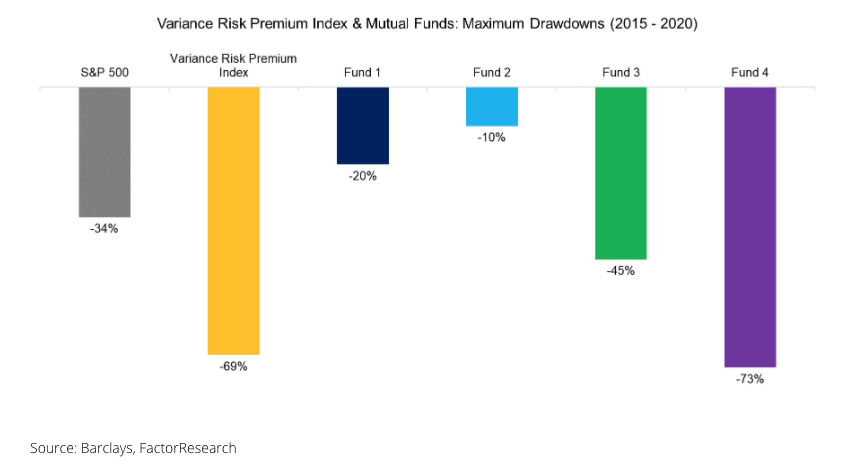

Contrasting the maximum drawdowns between 2015 and 2020 shows dramatic losses in some of these products, highlighting the riskiness of this strategy. It is important to note, though, that drawdowns themselves can be acceptable to investors, if they provide diversifications benefits.

Unfortunately, the VRP index and mutual funds cratered when the stock market crashed during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, essentially failing to provide uncorrelated returns for a traditional equity-bond portfolio.

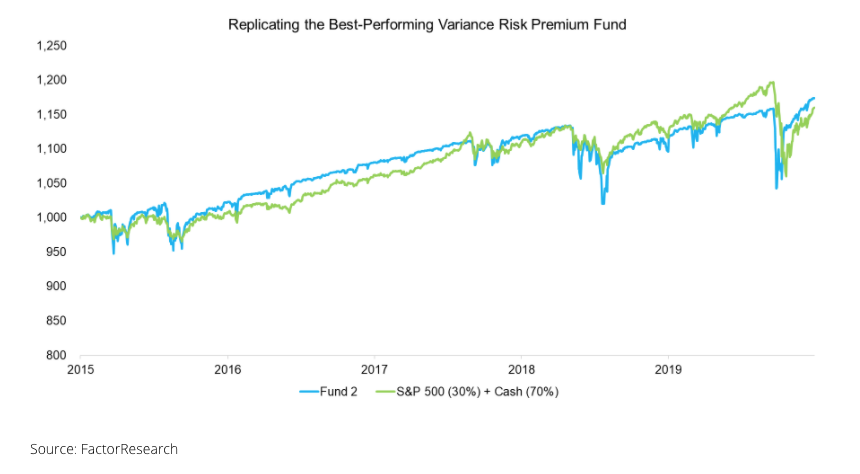

One of the products, Fund 2, has been a commercial success as it manages more than $1.8 billion in assets. At first glance, the fund seems to have generated high risk-adjusted returns in recent years and had a significantly lower drawdown during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 than the S&P 500 (-10% versus -34%).

However, a closer examination reveals that the strategy could have been efficiently replicated by a simple combination of equities via the S&P 500 (30%) and a zero-interest cash position (70%). It raises the question why investors have allocated such large amounts of capital to a complex product that does not provide any unique characteristics.

Further thoughts

Harvesting the variance risk premium has a sound theoretical basis as investors are willing to pay a premium for hedging themselves with options against market downturns. Selling insurance tends to be a profitable business.

However, as in many strategies that originate in quantitative research, there is a significant difference between theoretical and realised returns. The analysis can be challenged for the small sample size of one index and four mutual funds, but it is worth recalling that these represent the surviving products, biasing the results upwards. The worst funds have already been liquidated.

NICOLAS RABENER is the managing director of FactorResearch, which provides quantitative solutions for factor investing.

Also by Nicolas Rabener:

Are tactical ETFs worth using?

Did smart beta fixed-income ETFs pass the COVID test?

How did different risk factors perform in Q1?

Why you should avoid thematic funds

If you found this article interesting, we think you’ll enjoy these as well:

The widening valuation spread between growth and value

US value and growth performance under the microscope

How long do top-quartile funds stay there?

What will the recession mean for small-cap stocks?

Is market-cap indexing a form of momentum investing?