You won’t find a single economist predicting a speedy recovery from the huge jolt dealt to the global economy by the coronavirus crisis. JPMorgan forecasts that the US economy will shrink by 40% in the second quarter. If the the US and Europe are hit by a second wave of COVID-19, or if a vaccine isn’t developed in the next few months, we could be heading for a prolonged depression of the kind the world hasn’t witnessed since the 1930s.

So what does all this mean for smaller companies specifically and for those who invest in them? As this article from DIMENSIONAL FUND ADVISORS explains, the outlook may be grim, but the fact we’re living in challenging economic times should not deter you from investing in small-cap stocks.

With recession concerns intensifying in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, investors may be wondering whether small cap stocks are poised to struggle. Are small companies more vulnerable now than they have been during other periods of economic distress? And what are the implications for the size premium?

Even if the economy has entered a recession, it does not necessarily follow that small cap stocks should underperform. Why? Current market prices already reflect expectations about future cash flows, including any impact of an economic downturn. So even if the effects of a recession are more heavily borne by smaller companies, small cap stocks can still deliver higher expected returns.

Turning to the data, the first question we want to answer is whether small cap companies were displaying any unusual trends leading into the current crisis. If the financial characteristics of small cap firms in recent years have been in line with long-term averages, we can use historical data to help us understand the potential range of outcomes going forward.

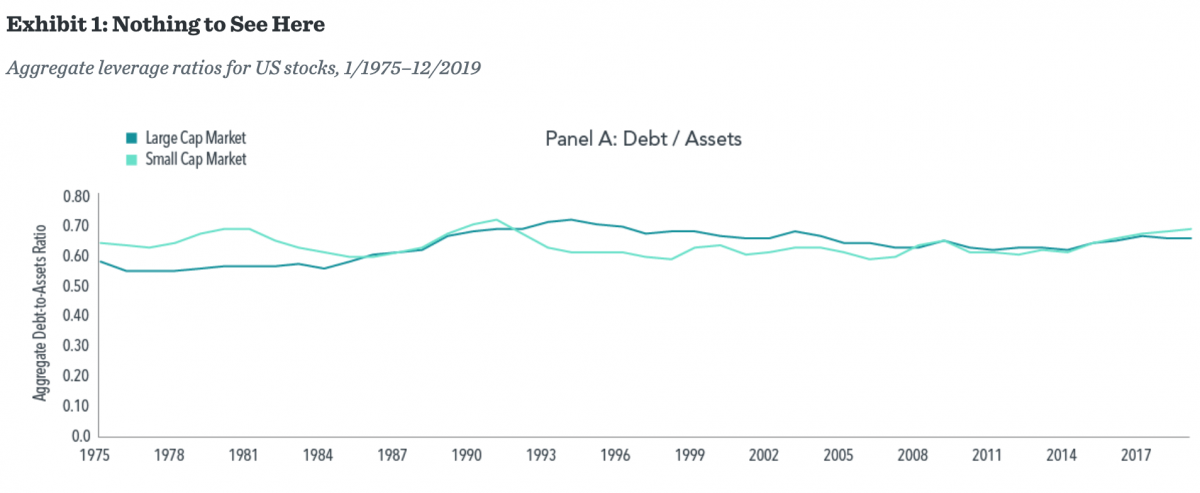

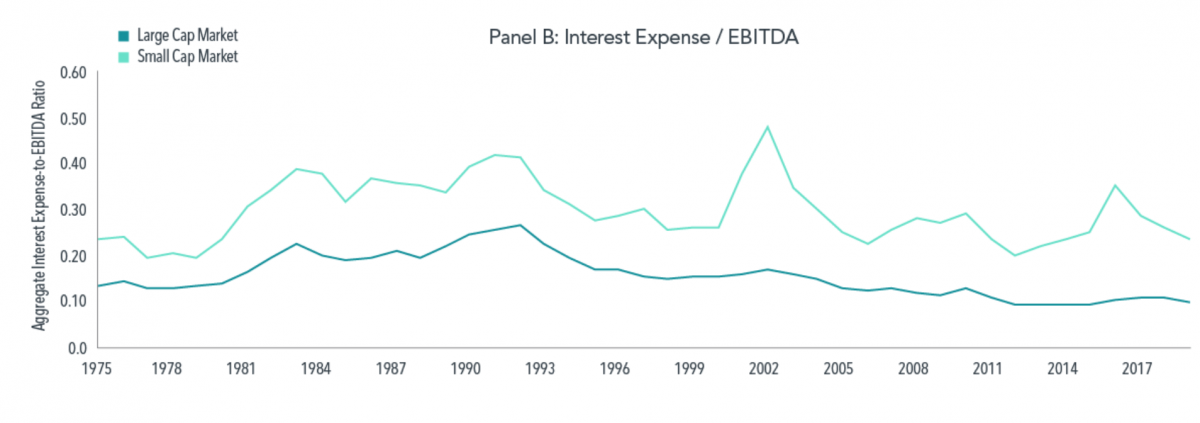

One common measure of a company’s relative strength is its leverage or the relative value of its debt. A company whose financial standing has deteriorated during an economic downturn may experience rising leverage that is less sustainable over a long period. When measured using total debt scaled by total assets (Panel A of Exhibit 1), aggregate leverage rates for US small caps have actually been similar to those for US large caps, and relatively stable through time. Another conventional measure of leverage is interest expense scaled by EBITDA, a way to assess companies’ ability to pay their debt through earnings. As illustrated in Panel B of Exhibit 1, US small caps appear more highly levered than US large caps, but their leverage has remained in line with historical trends.

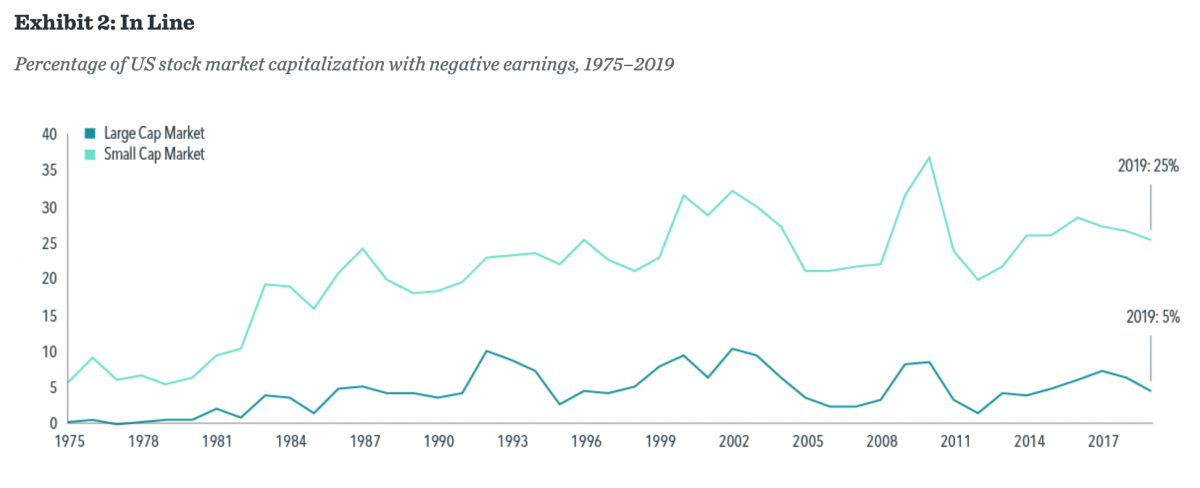

Another characteristic worth assessing is the proportion of companies with negative earnings. A company with negative earnings going into a recession may face worse odds of persevering through the downturn. Recently, about 25% of the US small cap market reported negative earnings, compared with about 5% of the US large cap market. However, as the historical data in Exhibit 2 illustrate, this is not a particularly new development. The current proportion of US small caps with negative earnings is in line with the norm over the past several decades, both in absolute terms and relative to US large caps.

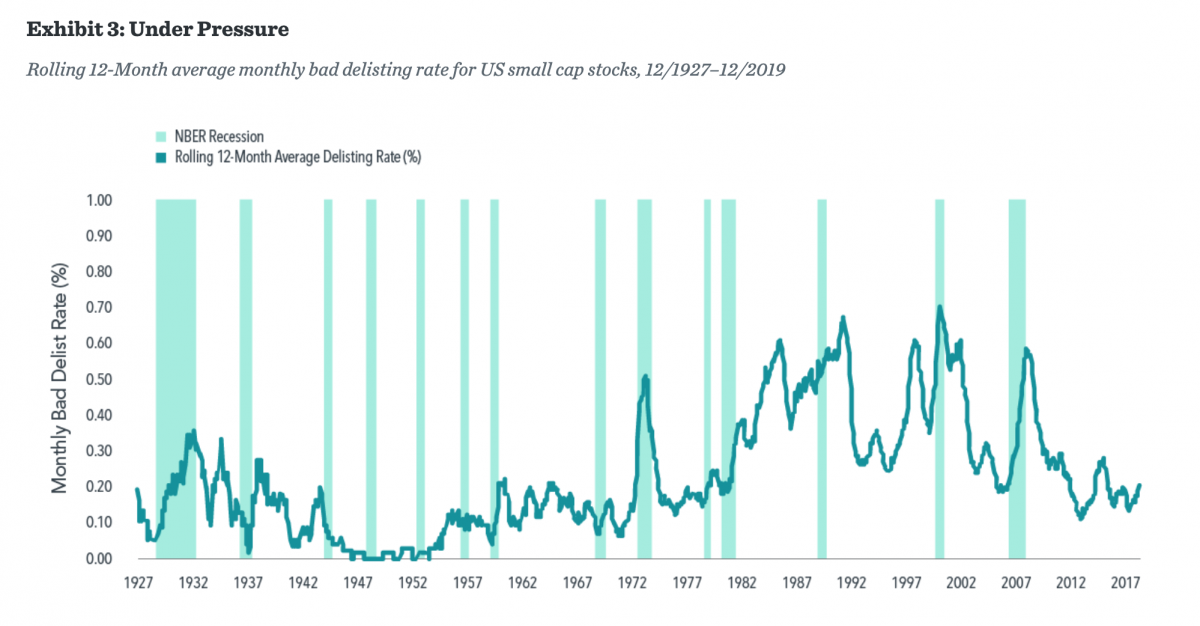

These data counter the notion that small caps had become particularly vulnerable before the current economic downturn. Therefore, we can use long-run historical data to inform expectations for small cap firms in this environment. For example, historical data on stock delistings suggest that, on average, the stocks of small cap firms tend to be delisted for “bad” reasons (such as liquidations, bankruptcies, or inability to meet exchange listing criteria) more frequently than large cap stocks. From 1927 to 2019, the average annual rate of bad delistings for US small cap stocks was about 2.7%, more than six times the rate for US large caps (0.4%). As Exhibit 3 illustrates, the rate of bad delistings among US small caps has been higher around economic recessions.

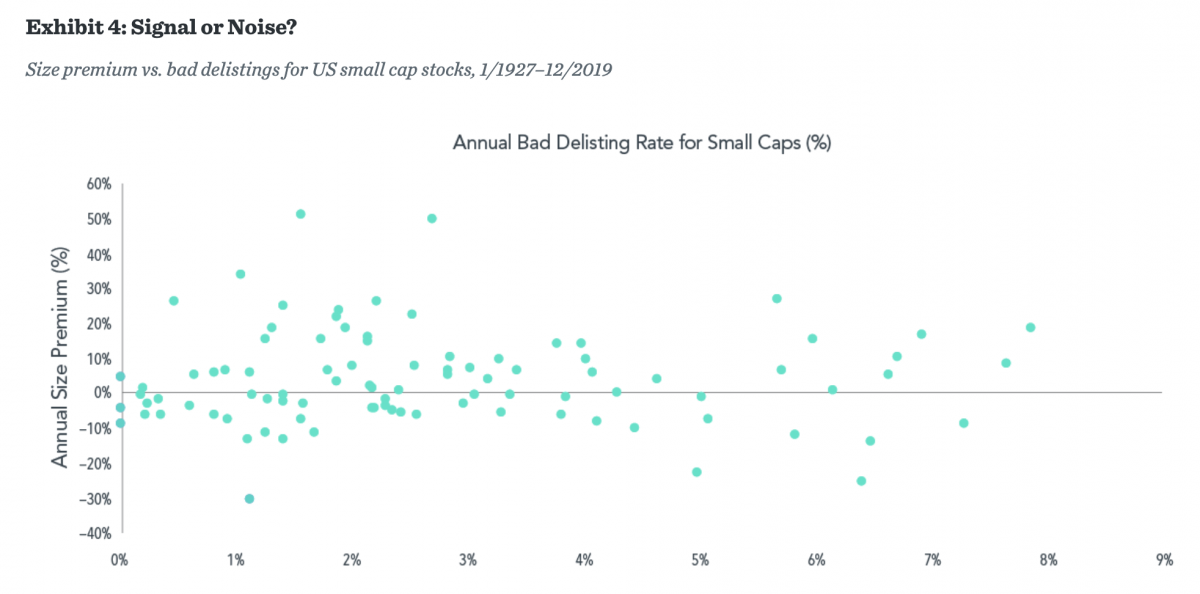

The relevant question for investors is whether this pattern will impact the future performance of small cap stocks. It’s important to remember that even if small companies are going “bust” more frequently than larger companies, that doesn’t necessarily imply that returns for all small companies will be lower. Rather, it is sensible to believe that the expected return for small cap stocks as an asset class compensates for the possibility that some individual companies may go out of business.

To assess this, we plot the annual returns for the Fama/French US size factor (which shows how small cap stocks have performed relative to large cap stocks) against the bad delisting rate for US small cap stocks in Exhibit 4. There has been no relation between the rate of delistings for US small caps and the performance of the size premium. Nine of the 16 years in which US small cap delistings exceeded 5% were associated with a positive size premium.

Even during volatile times, markets continue to function, connecting willing buyers and sellers. Market prices quickly incorporate new information and reflect the aggregate expectations of buyers and sellers — including information about the financial health of small cap companies and the impact that coronavirus developments might have on their future performance.

Investors can put themselves in a better position to pursue their financial goals by investing in a broadly diversified portfolio that includes small cap stocks. Diversification can help reduce unnecessary risks associated with the performance of specific companies or industries as well as increase the reliability of outcomes.1

GLOSSARY

Small cap: Refers to stocks with a relatively small market capitalisation.

Large cap: Refers to a company with a relatively large market capitalisation.

Market capitalisation: The total market value of a company’s outstanding shares, computed as price times shares outstanding.

Size premium: The return difference between small capitalisation stocks and large capitalisation stocks.

Leverage: Using borrowed money to increase the potential return of an investment.

Delisting: The removal of a listed security from a stock exchange.

This article first appeared on the Dimensional Fund Advisors blog, Dimensional Perspectives.

Interested in more insights from Dimensional? Here are some more articles from this series:

How worried should investors be about the recession?

Remember, you’ve trained for this

Study provides fresh insight on bond returns

The outsize rewards for owning the top-performing stocks

You can’t predict market movements: 2019 is a case in point

DFA’s new investment factor explained