Alternative investments are suddenly all the rage, with both institutional and retail investors increasing their exposure. Alternative strategies, according to Morningstar’s definition, “attempt to expand, diversify, or eliminate the dominant risk factors contained in traditional market indexes… and tend to focus on capital preservation, long-term portfolio diversification, or enhanced risk-adjusted returns in isolation or combination.” But how successful have such strategies been?

Morningstar’s JOHN REKENTHALER has been analysing the role of alternative investments in portfolios over the last 15 years. His conclusion is that, in that time, “the common, cheap, and everyday solution outdid every one of Wall Street’s esoteric, expensive, and specialised responses.”

Last month, funds that hold alternative investments enjoyed higher net sales than did either U.S. stock or taxable-bond funds. That hadn’t occurred in six years. In response to alternatives’ renewed popularity, my editor suggested this column.

Her wish, my command. For this article, I have addressed all fund categories in Morningstar’s Alternatives Category Group that have at least a 15-year track record. I also included categories that invest in: 1) commodities, 2) real estate, and 3) precious-metals stocks. (Funds in the latter two categories hold equities, which aren’t really “alternatives,” but as they are often used to diversify portfolios, I added them.) The analysis covers both mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. However, the results are mostly from mutual funds, as few alternative ETFs have long histories.

Total returns

I started by examining the total returns for each fund category, for the 15-year stretch from February 2007 through January 2022. From one perspective, this period flatters alternative funds, since it includes the 2008 global financial crisis, during which they generally fared well but had few shareholders. In other words, they enjoyed paper gains. From another perspective, though, this era penalises alternatives, because it consisted largely of a stock-and-bond bull market.

That seems like a reasonable compromise. Alternatives would look better if conventional securities had performed worse. On the other hand, because the period was bookended with sharp losses (with another jolt last month), alternatives were given ample opportunity to demonstrate their attributes.

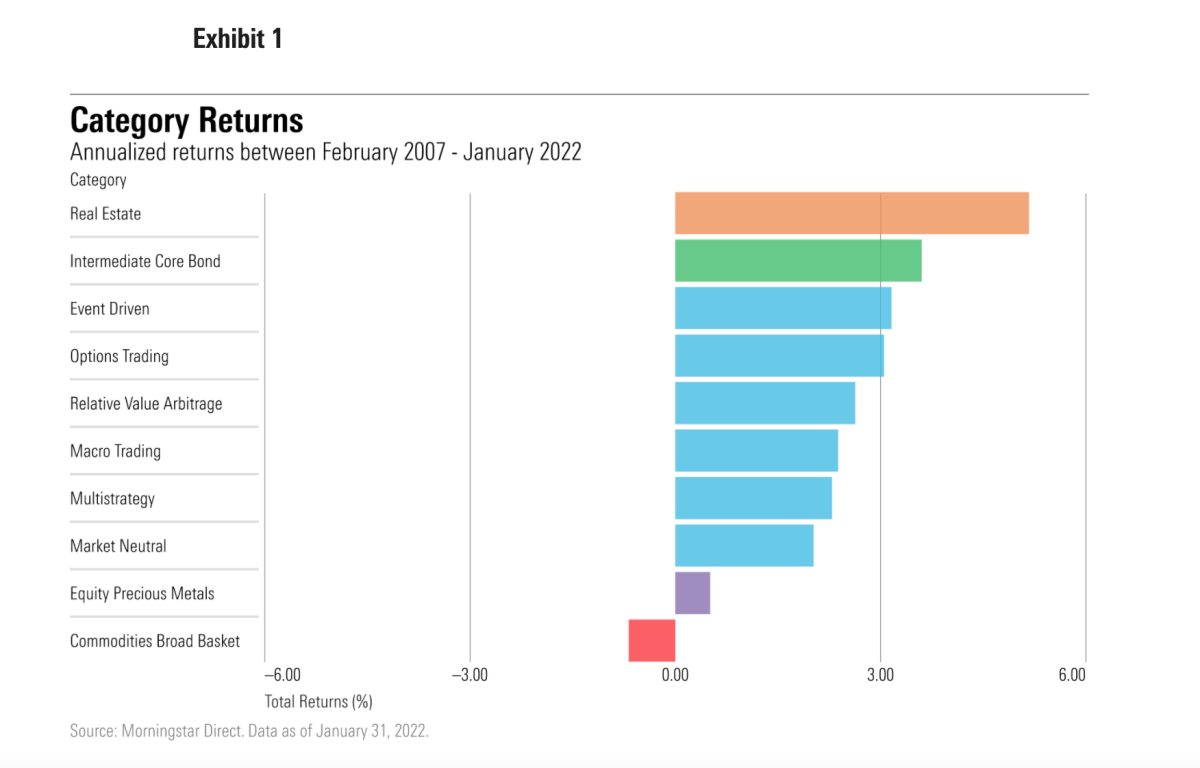

The following exhibit provides the returns. The six categories that occupy Morningstar’s Alternatives group are each depicted in blue, as they are broadly similar. All follow strategies that are based mostly on equities. Commodities, real estate, and precious metals are shown in red, orange, and purple. Finally, the exhibit also contains intermediate core bond funds, shown in green. Such funds obviously are not “alternatives.” But they are relevant, as they represent the competition. Rather than own alternatives, investors could simply retain all their bonds.

The highest returns came from real estate, which was to be expected, given that such funds had the highest stock-market exposure (aside from the precious-metals equities category, that is, but gold stocks don’t necessarily move with the overall stock market) Then came bonds, followed by the other five categories from the Alternatives Category Group. Over time, those categories tend to perform as a unit. At bottom were the final two real assets, precious metals equity and commodities.

That’s a disappointing showing. Over 15 years, only one of the nine investment alternatives listed in this column outgained that which they sought to replace. What’s more, the winning real estate category was several times more volatile than were intermediate core bond funds. Thus, from a risk-adjusted viewpoint, every one of the alternatives trailed the simple, safe, and obvious choice.

Assessing correlations

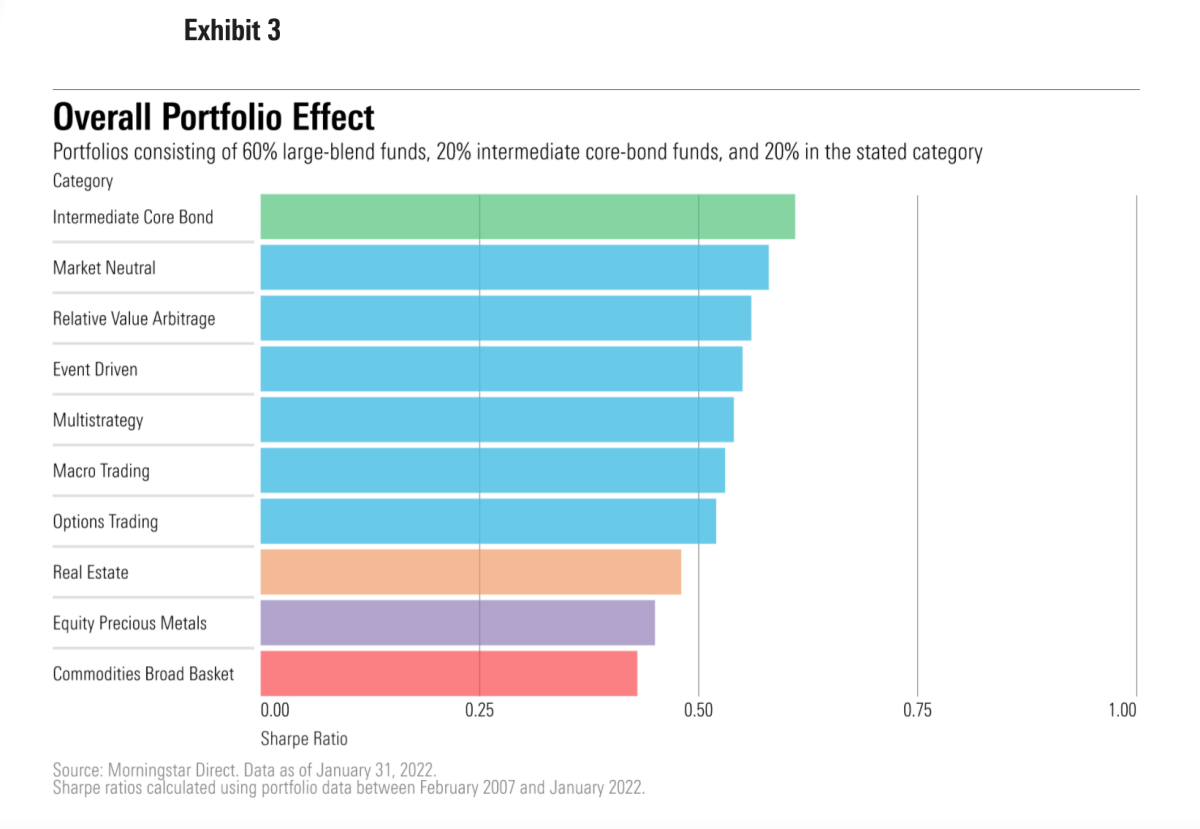

As alternatives exist to diversify portfolios, one shouldn’t dwell on their stand-alone results. That said, alternatives must record returns that are at least respectable. After all, how much good can come from an asset that averages a 2.3% annual gain, as with macro trading funds? Unless that investment consistently zigs when the rest of the portfolio zags — and perhaps not even then–its sluggish returns will outweigh its diversification benefits.

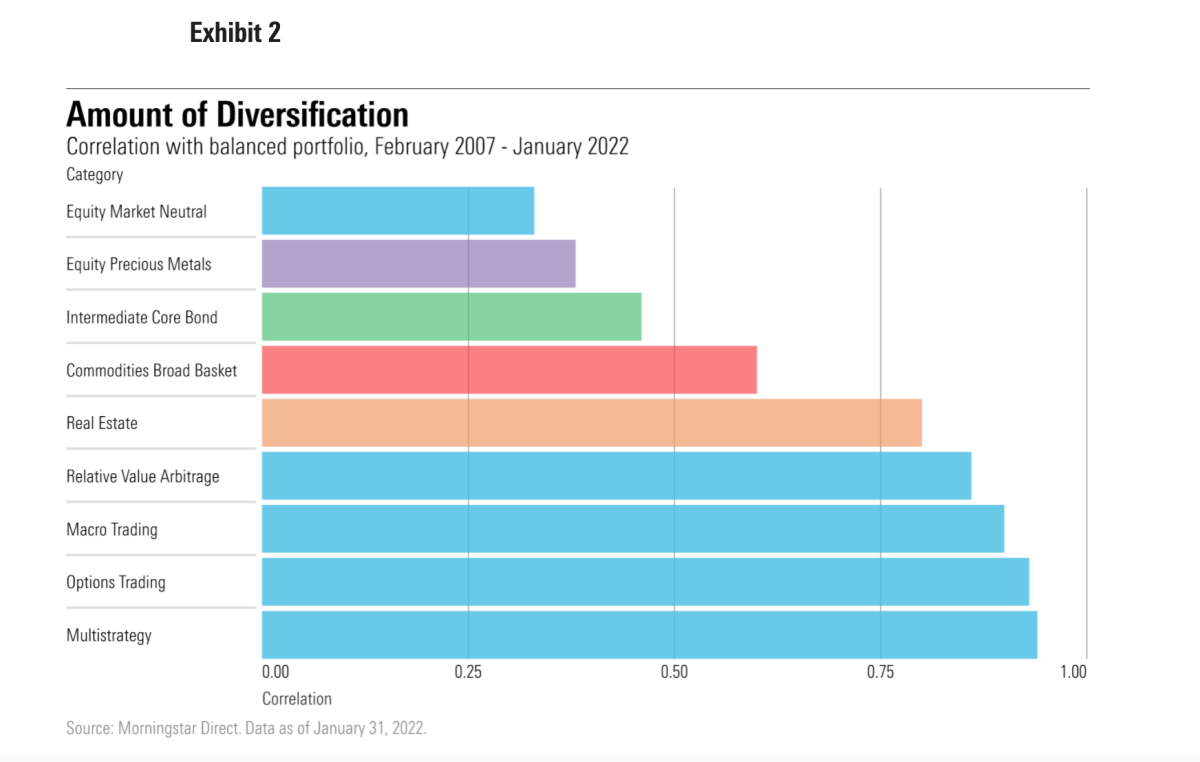

Unfortunately, the diversification benefits for alternatives have also been less advertised. The next exhibit shows the correlation over the period between each of the fund categories and a traditional balanced fund that holds 60% of its assets in large-blend U.S. stock funds and 40% in intermediate core bond funds. A negative score would be ideal, indicating that the category tends to move the opposite way of conventional assets. Failing that, a low positive score would be useful.

Oh, dear. Not only were all the scores positive, but seven of the 10 categories recorded correlations of at least 0.60. The only exceptions were market neutral and precious-metals funds, which had provided notably low returns, and intermediate core bond funds. The latter example suggests a problem. Even though this exercise was rigged against bond funds, because the test investment contained a 40% position in such issues, they nevertheless provided better diversification than did most of the “alternatives”.

In hindsight, this wasn’t a shock. As previously mentioned, the blue categories largely invest in equities. Yes, they hedge, but at heart they are equity funds. Aside from market-neutral funds, which mostly live up their billing by not being strongly correlated with equity returns, the other categories tend to follow the lead of the stock market. Think of them more as sedated forms of equity investing than as true alternatives. The same holds for real estate funds, which invest mainly in REITs, and thus are strongly affected by the stock market’s currents.

That commodities registered such a high correlation with a balanced portfolio surprised me. Then again, until very recently the threat to equity prices came not from inflation, but instead from concerns about recession, as during the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 coronavirus downturn. During such environments, commodity prices also slump, due to declining industrial demands. Commodities can rise when the stock market falls — but only under certain conditions.

The verdict is lamentably clear. As Jack Bogle might have predicted — I don’t recall him commenting on alternatives funds, but one needn’t be a Boglehead to anticipate this particular response — the common, cheap, and everyday solution outdid every one of Wall Street’s esoteric, expensive, and specialised responses.

Whether alternative investments will be similarly useless over the next 15 years remains to be seen. Should inflation prove more than temporary, commodities and precious-metals stocks might thrive, as they did during the 1970s. And while real estate funds won’t offer much diversification, they might compensate for that shortcoming with superior total returns.

Unfortunately, I cannot muster any potential enthusiasm for the blue categories. They promised to accomplish what bonds could not. They failed. I see no reason why the future will bring a different result.

JOHN REKENTHALER is a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar’s investment research department. This article was first published on the Morningstar blog.

MORE FROM MORNINGSTAR

The percentage of outperforming funds fell again in 2021

Active share has been a big disappointment

What should investors look for in an index?

Active managers failed their Covid test

Thematic funds: good stories, poor investments

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXII