The problem with getting to the truth about investing is that everyone in the industry has some sort of vested interest. I often find myself wondering how much better informed investors would be if, instead of always seeking the opinions of people with something to sell, the financial media spent more time talking to distinguished academics who’ve devoted their careers to studying it.

ELROY DIMSON is one the first academics I would point financial journalists towards. Professor Dimson chairs the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management at Cambridge Judge Business School, and is Emeritus Professor of Finance at London Business School.

His research focuses primarily on investing for the long term, and together with his colleagues Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, he has become well known for this studies of the investment performance of different financial assets in 23 countries since 1900.

In the first part of a wide-ranging two-part interview, Professor Dimson discusses the lessons that investors can learn from stock market history, and in particular the importance of diversification. He also gives his opinions on the long-term direction of interest rates.

Professor Dimson, first and foremost you’re a market historian. Generally speaking, what can market history teach investors today?

If you plot through the history using the work that I’ve done with my London Business School colleagues Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, where we’ve looked at the performance of 23 individual stock markets from 1900, the emphasis has to be on diversification.

Some of those markets prospered on the way in a direction that was largely onwards and upwards, although there were some setbacks. There are counter-examples like Russia. Anyone who invested all their money in the Russian market lost it all in October 1917. In China, the assets started to disappear in about 1941 and by 1949 they’d gone completely.

If they’d invested in Austria they would have been disappointed. Austria was an empire that embraced countries like Czechoslovakia, Slovenia, part of Italy, Hungary, Austria itself, and so forth. But a lot of that was destined to disappear, and Austria today is a small proportion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

So we’ve seen empires like the Russian and the Austrian Empire collapse, and we’ve seen countries that have confiscated assets like China and Russia, and individual investors who invest a single country were more exposed to these factors than if they invested internationally. The importance of diversification is clear within markets, but across markets it is also worthwhile. And it’s easier today than it was 100 years ago to invest internationally.

If the 20th century saw, to use your own phrase, the “triumph of the optimists”, what are the chances that the 21st century will see the triumph of the pessimists?

We published our book Triumph of the Optimists in the very early 2000s, and it was essentially a history of the 20th century. We called it that because our view was that, back in 1900, only real optimists would have poured their money into industrial and commercial common stocks and that many risk-averse investors would have played safe with government securities.

It was the optimists, the people who were not frightened, who performed very well. In the 21st century we’ve had two major setbacks — in 2001 approximately and 2008. So the early years of the 21st century were not promising.

Our view is that people in the 20th century were luckier than they might reasonably have expected. But one doesn’t make forecasts like that — it’s too dangerous. You should expect that people will get about a normal reward for stock market risk. To regard the 21st century as a period in which the pessimists are the winners, that would mean that investors in government bonds are the winners. I find that rather far-fetched, to be honest. I’d expect that, over the long-term, equity investors will outperform investors in government securities.

Government bonds, of course, have done very well over the last several decades. As interest rates have come right down, bond values have gone up and bond investors have done well. Interest rates can’t get much lower, so the upside for risk-averse investors is quite limited and long-term investors, in my view, should have a significant holding, though not all of their money, in equities.

As you say, it’s dangerous to make long-term predictions. But do you have a view on the long-term direction of interest rates?

When I say interest rates can’t get much lower, they can get a bit lower. But we had interest rates in the 1980s, long-term bonds in the US and the UK, for example, that had percentage yields in the teens. They were markedly above ten per cent in many years.

They’ve moved down to being in the order of a couple of percentage points or, in real terms, stripping out inflation, round about zero. With real interest rates at zero, or maybe minus one or minus two, they can’t keep moving down to being minus five or minus ten. So the big move is already behind us.

What can we expect looking forward? If you look at the structure of the yield curve, it does price in an increase in interest rates of a fairly modest amount. But as for returning to the high inflation rates of the 1980s and seeing, therefore, interest rates going back up to that level, I think that’s unlikely. The world’s a different place now.

One of the subjects you’ve tackled in the work you do each year for the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook is the rise and fall of different industries. What’s the lesson for investors there? Is it a good idea to rotate between industries?

The question is, should you be trying to identify which sectors will do well and which sectors will do badly? So think back to the beginning of the 20th century. Should you have invested in automobiles? Well, most people would have chosen the wrong automobile company; and most of them went bankrupt.

One of the problems in identifying winning sectors is that it’s extremely difficult to tell which ones will do well and which ones will do badly, especially if you’re a long-term investor. Railroads, for example, were overtaken in the middle of the 20th century by airlines, trucking and shipping. But if we fast forward through the bankruptcy of the American railroad system with the Penn Central collapse in the 1960s, all the way through to 2015, it turns out that the best performing transportation industry was the railway system.

So it can be the case that you buy into a tired industry, or one which appears to have fewer growth prospects, but if you buy at the right price, there may at the end be a worthwhile return.

We find this a number of times over. It’s the opposite to buying growth stocks, which come out with a froth and excite people that they are new ideas for the future, and which then start their life at an excessive price, which defies earning a good return in the secondary market.

So instead of rotating between different industries, your view is that investors should stay broadly diversified and focus on the long term?

It is all about diversification, and in fact the diversification story takes you further than you might imagine. If you’re in a large market like the United States, the story sounds as though it’s about diversifying across lots of different companies and lots of different sectors. But there are many countries where the number of industry sectors is extremely small — three or fewer — and so, in those cases, an attempt to diversify across industries itself is very difficult unless you diversify globally.

So as soon as you think about diversifying across different types of companies, investors in a smaller market are forced to think about investing internationally.

In Part 2: Elroy Dimson discusses ethical investing and the best way to go about it. He also gives his opinion on whether collectibles such as fines wines and classic cars make good investments.

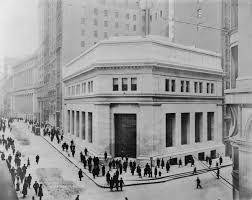

Picture: The New York Stock Exchange in 1914