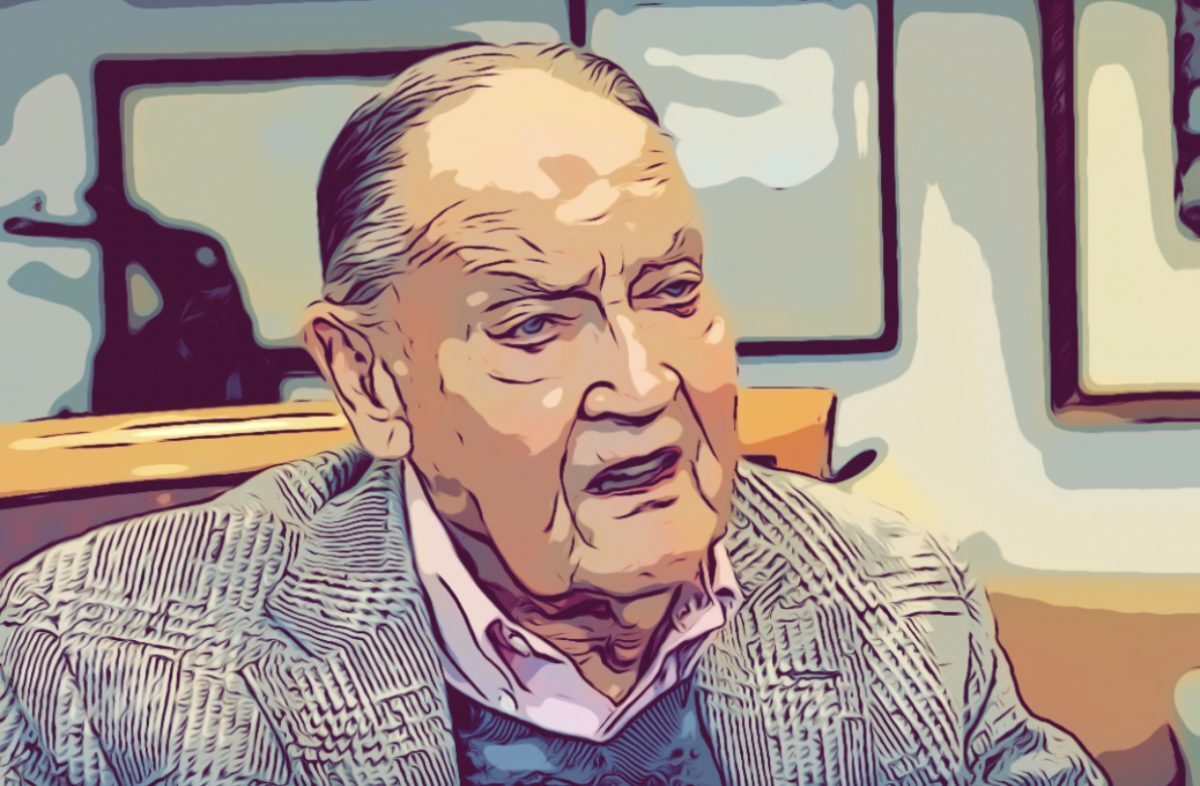

Jack Bogle, one of the most influential figures in the global investment industry, died four years ago this week. He was the founder and chief executive of The Vanguard Group and is credited with creating the index fund. To mark the anniversary of his death, ROBIN POWELL has been interviewing ERIC BALCHUNAS, a Senior ETF Analyst at Bloomberg, who followed Bogle’s career closely for many years. Balchunas is the author of The Bogle Effect, which assesses the impact that Bogle has had, both during his lifetime and in the years since his death. So, what is Jack Bogle’s legacy? And what was he like as a person?

RP: Eric, why did you decide to write your book, The Bogle Effect?

EB: Well, I was sitting on three-and-a-half hours of audio recordings of me interviewing Bogle in his office, and debating issues with him. He was really fired up in our interviews. He really wanted to debate ETFs. He was not a huge fan of ETFs. I’m an ETF analyst, so there was a lot of rich content there.

In his last interview, he was very prophetic. He talked about what would happen with asset managers and what would happen with the advisory business. He gave predictions on everything. And I thought this really should be in a book. This guy was probably going to have the biggest impact of any human being on this industry, so I just felt like I would regret it if I didn’t write one.

Another reason I wrote the book is that not a lot of people cover Vanguard or even know a lot about them, because Vanguard is a private company. But I had a lot of data on them. So the book tells you what’s going on in every part of the whole investing ecosystem and how it’s changing rapidly. And, largely, that can be traced back to Bogle.

I was privileged to interview Bogle in his office on two occasions, but you spent much more time with him than I did. How did you find him as a person?

Whenever I’d go into Bogle’s office, I felt like I was in my grandfather’s house. There’s a big difference between the World War II generation and the Boomer generation. Bogle was a World War II guy. He wasn’t in the war per se, but he had oil paintings of ships and revolutionary fighters on the wall. My grandfather was the same way; that was a big deal for that generation.

And that generation can be so savage in their wit. Bogle had this savagery to him, especially about active managers and ETFs and, well, just about everything that wasn’t the total market index fund. But you knew that he was a great, generous, loving person — a soft guy with this hard-shell exterior.

Bogle did something else that was popular with the World War II generation, which is written communication that isn’t necessarily meant for public consumption. He would write emails after you visited. When I wrote my first book, he said he purchased four copies. It was a book on ETFs, so if anybody should not buy the book it would be Bogle because he hated ETFs. But he was just that kind of guy.

One time in his office, we finished our interview, and he invited me to go and have lunch at the campus cafeteria. As we walked over there, everybody was coming up and saying, “Hello, Mr Bogle”. You could tell there was genuine love for the guy, even though he was being really quite critical of Vanguard at the time. He chose a seat right in the middle of the cafeteria, among all these young, young people, but he didn’t care. He was totally at home and comfortable. Sometimes you get big and famous and you go in the other direction. You avoid people. He was a man of the people, literally.

Something that comes across strongly in your book is how Bogle inspired others in their careers. The lawyer Jerry Schlichter is an example.

Yes, someone said to me, “You’ve got to talk to this guy Jerry Schlichter.” He’s a lawyer who found that 401k pension plans were on the take from active mutual fund companies. The fund companies and the sponsors were both getting paid to put people in really expensive, high-cost, share classes, knowing that it probably was not the best deal for them. So Schlichter went and sued Fortune 500 companies, including Lockheed Martin. That’s a big deal. These companies have lots of lawyers. And before Schlichter did that, he had to remortgage his house. He went to see Bogle and Bogle kind of gave him his blessing. Schlichter told me, “I needed that kind of spiritual energy to go through with this, because it was possible I would lose a lot of money and even my house. These Fortune 500 companies were not messing around.” And Schlichter ended up winning and winning and winning and winning. He even got the Supreme Court to rule in his favour. And now companies are changing their ways before they get sued by him. The whole 401K market has been changed by Jerry Schlichter, and Bogle was kind of involved in that, at least spiritually.

Someone else who was inspired by Jack Bogle was Warren Buffett. You interviewed Buffett for the book via email. Tell me about that.

Buffett doesn’t do email, but his assistant will tell him about certain emails he receives and he’ll dictate the reply back. I was told by my colleagues at Bloomberg TV, “Only email him if it’s really important. He probably won’t even get back to you anyway.” But I emailed him and put “Bogle book” in the subject line. And he got back within the day, and answered my four questions. At the beginning he said, “I’m swamped but I will help you out because it has to do with Jack and I’m a big fan.”

I asked him about the Berkshire Hathaway shareholders’ meeting that he invited Bogle to in 2017. Buffett said that was just a great moment for him and for everybody there. I also asked him about why he continues to advise investors to buy an S&P 500 index fund and not to try to pick active funds, and whether he’s worried that indexing is getting too big. He said he still advises people to go into index funds even as it gets bigger. If index funds continue to grow, he said there will be public policy issues down the line, but that’s a subject for another day. If you just buy the S&P 500 index fund, you’ll be in much better shape than trying anything else.

Concern about the growth of indexing was something that Bogle talked about towards the end of his life. And yet the active fund industry could deal with it by simply charging lower fees.

You’re exactly right. Active managers missed a major opportunity in the 1990s and 2000s, I think, and I talk about this in my book. If they had just passed on some economies of scale when they were rolling in gravy they would’ve really done a lot to fend off index funds. Indexing probably still would’ve been popular, but it wouldn’t have been the juggernaut that it is now.

When you are starting out as an active manager, you kind of need to charge one per cent because one per cent of nothing isn’t a lot. You’ve got to keep the lights on. The problem is, if you get 50 billion and you’re still charging one per cent, your revenue has gone up hugely. And a lot of that asset growth is just because the market went up; it’s not because you worked any harder.

So all they had to do was share some of those economies of scale through lower expense ratios. Vanguard did this like no one else. They started at 46 basis points in 1976, and it slowly went down to three basis points over 45 years. An active fund could have shared only a fraction of what Vanguard did and still, I think, banked a lot of goodwill. And by lowering your fee, what you also do is you really increase your chances of outperforming. A large fee just pushes you further and further back from the starting line, and then you’ve got to make up one, two or three per cent just to get to where the index fund is.

So it’s interesting to me that these active managers and all their analysts study industries for a living, and they know how things can be disrupted, and yet they were so open for disruption themselves. It didn’t need to be like this.

But it’s human nature, isn’t it, to protect what you have?

That’s right. In the book I say that I’m a greedy human like everyone else. And if I was running an asset manager that grew big, I would probably sponsor a sports stadium. I would hire a bunch of people. I’d give myself a big salary. I would do all these things thinking that I had earned it. And hey, this is all legal. I get it. That’s why I’m fascinated by Bogle. This guy went in completely the other direction — a direction no one else went in — and now, to an extent, everybody is forced to follow him. He brought the whole industry kicking and screaming to lower fees.

But they could have avoided a lot of this. And in the future, you’re right, if they cut their fees they can stop the Vanguard and BlackRock index fund juggernaut. But, the problem is that now it’s not just about lower fees. They’ve got to regain trust, and that’s really hard to do.

It’s a big question, but how would you summarise Jack Bogle’s legacy?

I’ve done the math. He’s already saved a trillion dollars for investors. That number grows by about 150 to 200 billion a year. So it’s an exponential growth. You could have him saving four trillion by the end of this decade, and that number will just grow and grow. So, had there not been Bogle, that four trillion in revenue would’ve gone to Wall Street. That alone is a huge legacy. The company Vanguard is also a huge legacy.

Jack Bogle’s legacy, in my opinion, can be distilled to this phrase: addition by subtraction. He was not just about lowering management fees. He also wanted to eliminate middlemen, especially ones who were just trying to mess with active funds. He wanted to get rid of trading. He was saying, let’s get rid of the turnover. Let’s get rid of the management fees. Let’s get rid of the brokers. And let’s just make investing as frictionless as possible. That is a lot of addition. And once you do that, and compounding starts to happen, you will be absolutely amazed at the outcome.

One way he illustrated that was to show a chart of the growth of $10,000. Say one investor earns five per cent annually, and the other gets seven per cent. That two per cent seems very small. But at the end of 50 years, the investor with the seven per cent return gets something like $380,000. So that extra two per cent gets you $180,000. You double your money in that time. And that’s only $10,000. Imagine if it’s a hundred thousand or a million. You can see where Bogle lived: 20, 30 years in the future where that compounding kicks in. And that’s where those little fees really become massive.

I think that’s ultimately what has built the financial industry into something enormous because getting one per cent of the assets seems so innocent, but the dollar fees that are gained from that because of compounding are huge. That’s what helped Bogle to sell this concept to people over time. Interestingly, 97.5% of Vanguard’s assets came after he stepped down as CEO. Think about that. That’s a lot. He laid the foundation that you could build the Empire State Building on. Yes, it’s counterintuitive to aim for average. It’s not obvious that a small percentage could be that big of a deal. But he was proved right over time.

The Bogle Effect: How John Bogle and Vanguard Turned Wall Street Inside Out and Saved Investors Trillions by Eric Balchunas is published by Matt Holt, an imprint of BenBella Books.

PREVIOUSLY ON TEBI

Just 2% of large-cap core funds have beaten the S&P 500 since 1993

Asset managers and their customers want different things

Do historic bear markets tell us anything about this one?

CONTENT FOR ADVICE FIRMS

Through our partners at Regis Media, TEBI provides a wide range of high-quality content for financial advice and planning firms. The material is designed to help educate clients and to engage with prospects.

As well as exclusive content, we also offer pre-produced videos, eGuides and articles which explain how investing works and the valuable role that a good financial adviser can play.

If you would like to find out more, why not visit the Regis Media website and YouTube channel? If you have any specific enquiries, email Robin Powell, who will be happy to help you.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIII