By LARRY SWEDROE

My May 7, 2021, article for The Evidence-Based Investor, Spac or Spam?, warned investors about investing in special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). It presented the evidence demonstrating that SPACs were highly likely to be losing propositions to their shareholders due to the unfavourable incentives built into the SPAC structure that result in SPAC sponsors doing well even if SPAC shareholders experience substantial losses. The article made the case that it was difficult to believe this was a sustainable arrangement, as at some point SPAC shareholders would become more skeptical of the mergers sponsors pitch. In other words, SPACs were a bubble that likely would burst. Forewarned was forearmed.

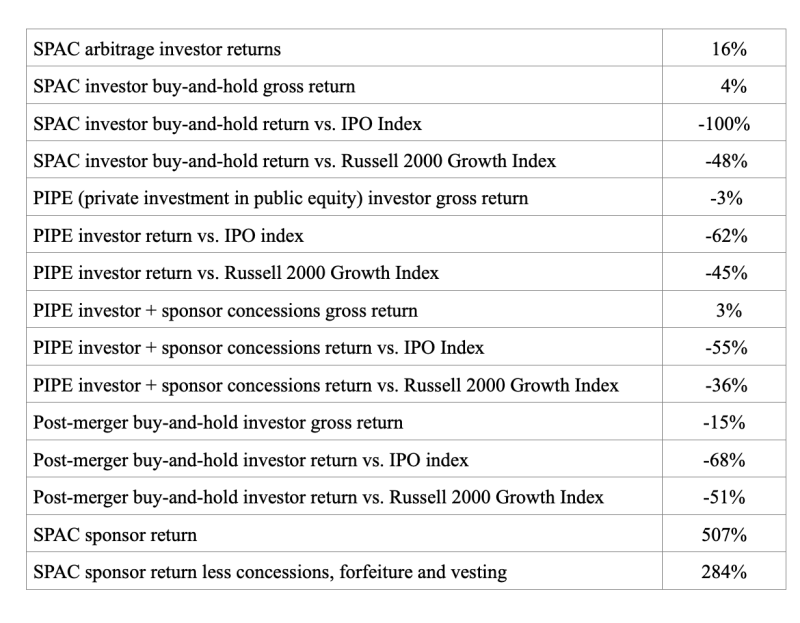

My August 31, 2021, TEBI article showed the evidence from a J.P. Morgan study that found enormous returns for SPAC sponsors, low positive absolute returns for SPAC arbitrage investors, and negative returns for everybody else. The table below provides a return analysis for investors in SPAC companies brought public or liquidated from January 1, 2019, to March 5, 2021, with the median cumulative returns through August 17, 2021:

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management, Bloomberg, Dealogic, JP Morgan Securities. August 17, 2021

New findings

Unfortunately, despite the poor results, Michael Klausner and Michael Ohlrogge found that SPAC sponsors have been evolving their offerings in ways that favor the sponsors and the SPAC arbitrage investors even more, to the detriment of other investors. Their March 2022 paper, SPACs are Evolving—and Getting Even Worse for Long-Term Investors, examined three developmental changes, each of which are designed to allow sponsors to continue to launch new SPAC IPOs, or to complete new SPAC mergers, while serving to divert even more value to parties in the SPAC transaction other than non-redeeming SPAC shareholders. As such, they are likely to lead to even larger losses for those non-redeeming SPAC shareholders going forward.

They began by noting that their research had led them to conclude: “SPACs are a very expensive way to take a company public (far more costly than traditional IPOs), and that SPAC shareholders that hold their shares through SPAC mergers bear those costs. In every single year of the past decade, the 12-month market-adjusted return to non-redeeming SPAC shareholders was negative. On the other hand, we found that other participants in SPAC transactions fared much better. We found that SPACs are very lucrative for investors who buy units in SPAC IPOs and who sell or redeem their shares prior to SPACs completing their mergers.” They added: “This strategy of buying in the IPO and exiting before the merger closes is extremely profitable – yielding an 11.6% annualized return with no risk of downside loss during our sample period. We found that nearly 100% of investors who buy in SPAC IPOs pursue such a strategy, either selling or redeeming their shares prior to SPAC mergers. These IPO-stage investors are dominated by a group of hedge funds colloquially to in the industry as the ‘SPAC Mafia’.” They then noted: “The gains to IPO investors and sponsors come at the expense of non-redeeming SPAC shareholders.”

The three new negative developments are:

- Development No. 1: Overfunding the trust account. In the basic SPAC structure, investors pay $10 per unit in an IPO, and the proceeds of the IPO are placed into a SPAC’s trust, managed by a third party. The trust funds are invested in U.S. Treasury securities, earning a modest return. In order to better entice IPO-stage investors, SPAC sponsors sometimes have “overfunded” SPAC trust accounts by placing additional funds in the trust. The money to overfund SPACs’ trust accounts comes from selling warrants (or units) to SPAC sponsors at the time of the IPO—warrants (or units) that dilute shareholders.

- Development No. 2: Short merger deadlines and expensive extensions. Until recently, SPAC charters have given SPACs a two-year deadline by which to complete a merger or liquidate. If a SPAC neared its two-year deadline without completing an acquisition, it could ask its shareholders to approve a charter amendment to extend the deadline, typically by a few months. Recent SPACs have diverged from this practice. The time allowed for newly launched SPACs to complete their mergers is now more typically just 15 months, and 30 percent of these SPACs allow just 12 months or less. At the same time, SPAC charters that allow shorter time periods for acquisitions also now typically allow the sponsor to unilaterally extend a SPAC’s deadline without seeking a shareholder vote or allowing an opportunity for shareholders to redeem. Instead, to trigger the extension, the sponsor must simply place a pre-specified amount of additional cash into the SPAC’s trust to increase the redemption price investors will eventually receive. That extra cash (for example, 2 percent per every three-month extension) is expensive, and the increase in SPAC costs can be almost as large as the typical SPAC IPO costs alone.

- Development No. 3: Private investors buying in with increasingly large and opaque discounts. Sponsors allow private investors to buy in to deals at steeper discounts compared to what public investors pay for shares. In addition, the terms are often extremely complex, favouring the private investor while non-redeeming public shareholders lose.

Their findings led Klausner and Ohlrogge to conclude: “SPAC costs are subtle, opaque, and poorly understood. This remains true today, both with respect to costs built into the basic SPAC structure and with respect to costs that are exacerbated by changes in that structure. A SPAC overfunding its trust may appear to be a positive innovation, making SPACs more investor friendly. In fact, however, it serves to make SPACs even more expensive and thus likely to yield even worse returns for non-redeeming SPAC shareholders.” Forewarned is forearmed.

One of the benefits of working with a good wealth advisor is that they prevent you from investing in products that were meant to be sold, never bought.

Postscript

On March 30, 2022, the Securities and Exchange Commission proposed a bevy of new requirements for SPACs and their takeover targets amid widespread concern that the vehicles skirt important investor protections. If implemented, the rules would make it harder for SPACs to raise money from investors and execute mergers. The SEC’s goal is to force the vehicles to meet similar regulatory standards as initial public offerings.

Important Disclosure: The information presented here is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is based upon third party data which may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Third party information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured author are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth® or Buckingham Strategic Partners®, collectively Buckingham Wealth Partners. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency have approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article. LSR-22-260

LARRY SWEDROE is Chief Research Officer at Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of numerous books on investing.

ALSO BY LARRY SWEDROE

Active share as a predictor of future performance

When stocks and bonds fall together

Is there a January effect in small-cap stocks?

Should value strategies adjust for intangibles?

Is social media making markets more efficient?

OUR STRATEGIC PARTNERS

Content such as this would not be possible without the support of our strategic partners, to whom we are very grateful.

TEBI’s principal partners in the UK are S&P Dow Jones Indices and Sparrows Capital. We also have a strategic partner in Ireland — Biograph Wealth Advisors, a financial planning firm in Dublin.

We are currently seeking partnerships in North America and Australasia with firms that share our evidence-based and client-focused philosophy. If you’re interested in finding out more, do get in touch.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXII