The fund management industry loves its product innovations. So does the financial media — not least because they provide something new to write about. But what are we to make of ANTs, the newest kid on the asset management block?

Actively managed non-transparent ETFs, or ANTs, debuted in the US in April. They come with many of the benefits of traditional exchange-traded funds.

But they have their disadvantages too. Some major fund providers, including Vanguard and State Street, are holding off on offering them. Also, ANTs have yet to be approved by regulators in Europe.

So are they worth investing in? BEN JOHNSON, director of passive funds research at Morningstar, looks at the pros and cons.

A new generation of exchange-traded funds debuted earlier this year. Actively managed non-transparent ETFs, or ANTs, share much in common with traditional ETFs. Their most distinctive feature is that they do not disclose the contents of their portfolios to the public on a daily basis. This helps prevent their managers from tipping their hand to the market.

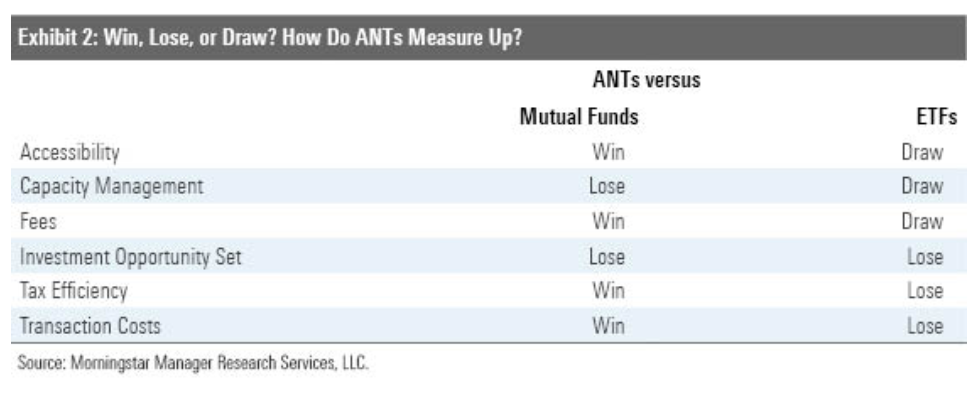

These ANTs offer investors meaningful benefits over traditional actively managed mutual funds. They also differ from conventional ETFs in nuanced but important ways. Investors should weigh the benefits and drawbacks of this novel fund type to decide whether it has a place in their portfolios.

ADVANTAGES

Broad availability, low investment minimums

Actively managed non-transparent ETFs function much like traditional ETFs. They trade on the stock exchange during normal market hours and can be bought and sold in an amount as small as a single share. This means they are available to any investor with a brokerage account and enough cash to cover the share price. Broad availability and low investment minimums are an advantage that ANTs (and ETFs more generally) boast over many mutual funds.

Fund flow costs externalised

Like conventional ETFs, ANTs create and redeem fund shares on an “in-kind” basis. This means that as investors add or remove money from the fund, portfolio managers either receive or give a basket of securities to a third party (an “authorised participant”) in exchange for ETF shares. As securities aren’t directly purchased or sold as part of this process, this means that: 1) Flows don’t create trading costs that are borne directly by long-term shareholders to the extent they would be in a mutual fund; and 2) Outflows from the fund don’t force portfolio managers to sell appreciated positions and thus don’t directly result in taxable capital gains distributions.

In this way the ETF wrapper externalises the costs associated with fund flows. Buyers and sellers of ETFs’ shares are on the hook for the cost of trading and any taxes that result from their transactions. Long-term shareholders are insulated from these costs. This is a key advantage ANTs — and all ETFs — have over traditional mutual funds.

Lower fees

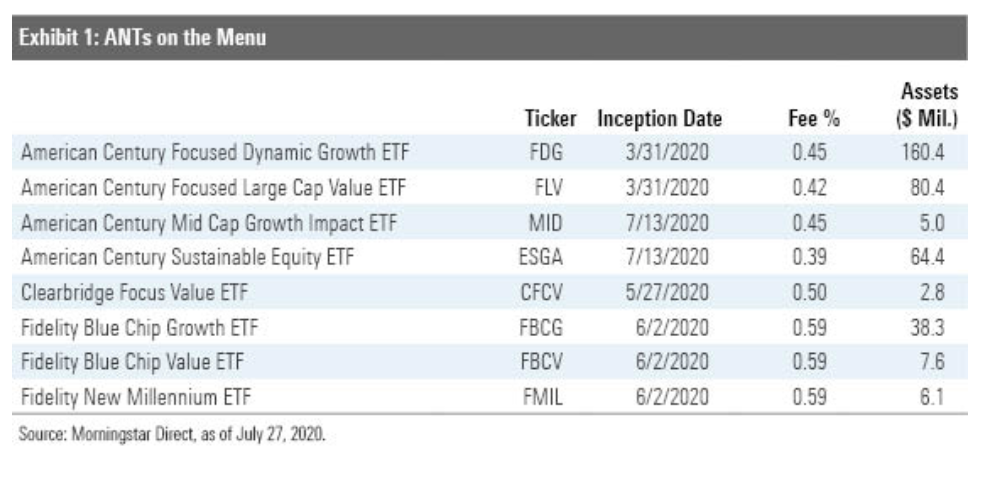

ANTs’ most durable advantage over retail share classes of mutual funds is their lower fees. No different from the overwhelming majority of traditional ETFs, ANTs’ fees do not have embedded marketing or distribution costs, and their shareholder record-keeping costs are much lower. These benefits are shared with investors in the form of a lower price tag. Of the eight ANTs on the menu today, all of them have lower fees than the retail share classes of their mutual fund counterparts and some charge less than the least-expensive institutional share class.

DISADVANTAGES

ANTs’ prospective benefits are meaningful. In cases where these funds offer access to strategies identical to those served up in mutual funds, they will also be directly measurable. But there are trade-offs involved.

Investment opportunities limited

ANTs limit portfolio managers’ palette. In order to help ensure that these funds’ prices closely mirror their net asset values and that bid-ask spreads are reasonable, they are currently limited to investing in securities that trade at the same time as the funds themselves. This limits ANTs to owning U.S. stocks, the American Depositary Receipts and Global Depositary Receipts of foreign companies, U.S Treasuries, U.S.-listed ETFs, and — in the case of one ANT format — foreign stocks that trade during U.S. market hours. Depending on the strategy, investing within one time zone may be a significant constraint on a manager’s ability to invest in their best ideas.

Unable to close funds to new investors

Managers may be further inhibited by capacity considerations. ETFs — ANTs included — cannot turn on their “No Vacancy” sign when capacity becomes a concern. Closing funds to new investors is a tactic that has been employed successfully by thoughtful managers in the past as a means of protecting existing shareholders. It often indicates a manager’s willingness to forgo financial gain (more assets mean more fees) to put fund shareholders’ best interests first. Without this option at their disposal, managers of ANTs will have to pay even closer attention to capacity considerations. Doing so will mean that many will favour large-cap stocks, where they have a wider berth to implement their ideas. That said, U.S. large caps are a highly efficient market, one that historically has been particularly challenging for stock-pickers.

Possibly less tax-efficient than conventional ETFs

While the ability to meet redemption requests in-kind will mean that ANTs will likely be far more tax-efficient than mutual funds, there is no guarantee that they will be as tax-efficient as traditional ETFs. Unlike traditional ETFs, ANTs do not have the ability to use custom redemption baskets — meeting redemption requests with the securities and tax lots of the manager’s choosing with an eye toward keeping a lid on taxable gains. Instead, ANTs must meet redemption requests with a basket that is identical to the one they have publicly disseminated that day. Removing managers’ ability to pick and choose which securities they’d like to purge from the portfolio to meet redemption requests may encumber their ability to maximize ANTs’ tax efficiency.

Another consideration regarding ANTs tax efficiency is two-way flow. The most tax-efficient ETFs regularly see investors come and go. Outflows are particularly important from a tax efficiency perspective as they allow portfolio managers to get rid of low-cost basis lots in a tax-free transaction and thus raise the portfolio’s cost basis in the process. But ANTs will likely never see the same degree of turnover as many mainline ETFs. This is because they cater to a narrower user base with one particular use case. These funds are meant for long-term allocators as a core portfolio building block. As such, flows will likely be steadier and one-directional (in) than many of the largest ETFs, which cater to a wider variety of investors (from hedge funds to individuals) and are used in a number of different ways (from core building blocks to tactical tools). So, while ANTs will likely be more tax-efficient than mutual funds, it is too soon to say that they’ll be every bit as tax-efficient as your typical ETF.

Lack of transparency

Transparency — or a lack thereof — is ANTs’ defining feature. Most conventional ETFs — and all of the actively managed variety thereof — disclose their full portfolios to the public on a daily basis. This is done as a matter of convention among index-tracking ETFs. It is required of active ETFs. Showing the market the whole of their portfolios each day ensures that market makers and authorised participants making the ETF machinery work have the information they need to quote fair prices and keep bid-ask spreads tight.

I’ve argued that transparency is an overrated benefit of the ETF wrapper — to the extent that it allows investors to know each and every last security their funds own and their corresponding weightings every single day. Buy-and-hold investors don’t need this information; the people who make sure that buy-and-hold investors are paying an accurate price for these funds and keeping transaction costs in check do. In the case of ANTs, portfolios are required to be disclosed on the same cadence as they are for mutual funds (quarterly, with a lag).

Higher transaction costs

To make sure that the ETF machinery has the information it needs to go, ANTs’ sponsors are required to provide additional information to the public (creation and redemption baskets and intraday NAVs). While this will help the market to price these funds, having incrementally less information and lower volumes is likely to equate to larger and more volatile bid-ask spreads for these funds. As such, transaction costs could eat into a portion of the fee savings that accrue to ANT investors. This is less of an issue the longer an investor’s anticipated holding period is. It becomes a bigger issue if they plan to make regular contributions to the fund. Ultimately, this incremental price investors pay to keep managers’ cards out of sight of wandering eyes must be weighed against the benefits that might accrue from allowing them to play it close to the vest.

SUMMARY

ANTs have a place. For investors allocating new money in taxable accounts that want to invest with a particular manager, they may become their vehicle of choice. They are easier to access, cheaper, and have the potential to be more tax-efficient than retail share classes of mutual funds.

But there’s a catch. ANT managers’ investment opportunities are limited and they forfeit the ability to close their funds as a means of managing capacity. Also, ANTs might not be as tax-efficient as conventional ETFs. And they may be more costly to trade. Investors should net all these considerations in deciding whether ANTs might fit within their portfolio.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

This article was first published on the Morningstar blog.

For more insights from our friends at Morningstar, take a look at these other recent articles:

Three truths about ESG investing

Fees crucial to ESG investing success — Morningstar

US fund fees cut in half in 20 years

Three risks you take when choosing a thematic fund

Is market-cap indexing a form of momentum investing?

A critical look at the arguments against index investing

Picture: Peter F. Wolf