By ROBIN POWELL

We’ve written many times on TEBI about the many myths that persist regarding index investing and the supposed superiority of active management.

As Morningstar’s Ben Johnson said the other day, they tend to be self-perpetuating. If we invest in active funds ourselves, or if we rely on their continued popularity for our livelihood as many in the investing industry do, we want them to be true.

That’s certainly the case with a myth I hear again and again, namely that index funds are fundamentally flawed because they include all the losers. On the other hand, we are told, a skilful active manager is able to identify stocks that are overvalued and remove them from their portfolios or steer clear of buying them in the first place.

“A passive fund manager is like a gullible dragon on Dragons’ Den,” an active manager posted on a social media the other day. “They say Yes to everyone, as soon as they step out of the lift”.

Of course, it seems a logical and appealing argument. No one likes the idea of owning stocks that are effectively duds.

But in fact it’s a complete red herring. You’re almost always better off in the long-term with a low-cost tracker — no matter how many losers it contains.

Let me explain.

Spotting the biggest losers isn’t easy

Identifying, in advance, a stock that’s about to flop is harder than you think. Even a spectacular collapse in a company’s share price can take the most successful fund managers by surprise. Several respected managers kept faith with the disgraced financial technology firm Wirecard for example; one “star” stockpicker went pretty much all-in.

We may disagree on the precise extent of market efficiency. The fact is, however, that markets are efficient enough that, once costs are factored in, only a tiny proportion of active managers consistently beat them in the long term. As Larry Swedroe put it the other day, you might find the occasional twenty dollar bill in the street, but don’t expect to earn a living out of it.

The challenge of market efficiency applies just as much to identifying losers as it does to spotting the winners. Active Manager X might think Stock A is a loser; Manager Y could have it down as a winner. They can’t both be right. Supposing Manager X sells the stock to Manager Y, one of them has to win at the other’s expense.

Fund managers are better at buying than selling

Another problem, research has shown, is that active managers devote more time to choosing which stocks to buy, and when to buy them, than identifying stocks to sell. As a result, they often end up holding stocks long after they’ve started to underperform (or indeed selling stocks that then go on to outperform).

In principle, of course, it’s perfectly possible for an active manager to sell a future loser which, by virtue of its mandate, a passive manager has to hold. In practice, though, it’s very difficult. In modern stock markets, where millions of market participants have access to the same information at the same time, active managers are rather less adept at weeding out the duds than they like to imply.

Almost ALL stocks are losers

An important point to remember here is that, extraordinary as it seems, the vast majority of stocks underperform the broader market.

In fact, a 2018 study by Professor Hendrick Bessembinder, a professor at Arizona State University, found that between 1926 and 2016, most US stocks not only underperformed the market but they underperformed Treasury bills as well. That’s right, most stocks were outperformed by one of the dullest and safest investments you could have bought.

In the 90-year period he looked at, Bessembinder calculated that the best-performing 4% of US stocks generated all of the market’s gains. In aggregate, the remaining 96% of stocks collectively matched the returns from Treasurys.

The technical term used to describe this phenomenon, whereby a very small number of stocks are responsible for the lion’s share of market returns, is positive skewness.

Skewness benefits indexers

So what does positive skewness mean in the context of active and passive investing?

On the face of it, you might have thought it supports the case for using an active manager. After all, 96% of all the stocks invested in by a hypothetical US equity index fund, bought in 1926 and held for 90 years, would have lagged the market. Why would you want to invest in that?

But what you’re forgetting is that the same fund would have also contained all of the winners. So, yes, the median (or middle) return, would have been negative. But, because of those big winners, the mean (or average) return would have been far, far higher.

What’s the most you can lose?

Think about it. What’s the most you can lose on any one stock? The answer is 100% of its value. In other words, the downside of a stock is capped at -100%. That’s the worst that can happen.

But the upside of a stock is unlimited. It can grow in value hundreds or thousands of times over. Indeed, Bessembinder showed how positive skewness compounds over time, with the winners continuing to grow at a faster rate than the losers.

Take Apple, for example. As Dr Tim Edwards explains in this recent video, Apple has been an astonishing success story. Over the last 20 years, the S&P 500 has gone up around 300%; Apple just more than 30,000%.

Some other big winners

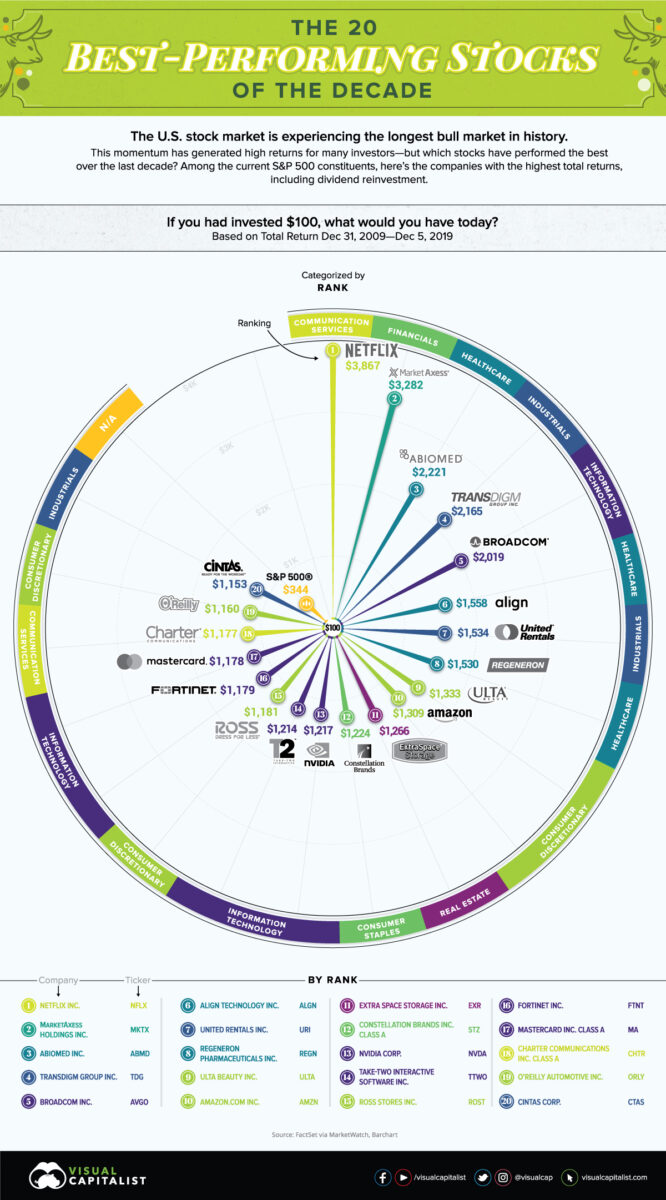

Nor is Apple an isolated case, as you can see from the chart above. In fact, it doesn’t even make a list of the 20 best-performing US stocks of the decade just ended, compiled by Visual Capitalist.

The best performer of the past ten years is Netflix. If you had invested $100 in the overall S&P 500 index on 31st December 2009, your investment would have grown to $344 by 5th December 2019. But if you had invested $100 in Netflix, your money would have grown to $3,687 over the same time period.

The same amount invested in Market Axess would have grown to $3,282, and $100 in ABIOMED to $2,221.

How many active managers held all 20?

There were thousands of actively managed US equity funds that investors had to choose from at the end of 2009. But what are the chances of any of those funds holding every one of those top 20 stocks for the entire ten-year period? I would be surprised if there was a single one.

Yet every one of those stocks was owned by an S&P 500 index fund.

The lessons to learn

In a nutshell, investors shouldn’t be swayed by the argument that, by choosing an active fund, they can avoid the worst performing stocks of the future.

True, you might be able to avoid some of the biggest losers, but simply by virtue of the fact there are so many of them you will almost inevitably be exposed to some of them.

But the bottom line is that the cost of trying to avoid the losers will almost certainly exceed the benefits. And I’m not taking here about the considerable extra cost involved in active investing, important thought that is. No, a far bigger cost is the near-certainty of losing out on some, or even all, of the biggest winners.

Of course, concentrated active managers who do spot some of the big winners can beat the market, but the odds are stacked against them.

So why not put the odds on your side by choosing a low-cost index fund and ensuring you own every one of them?

Want something else to read? Here are recent posts you may have missed which we think you will find interesting:

Active or passive — which is more volatile?

Was it ETFs that cause the markets to blow?

Safe yield RIP. What are your options now?

Seven simple rules of investing

Picture: Louis Hansel via Unsplash

© The Evidence-Based Investor