Robin writes:

As Jack Bogle used to say, the question of whether to invest in active funds or index funds is essentially down to cost. Over the long term, one option is hugely more expensive than the other.

But is it all about cost?

During filming for the documentary How to Win the Loser’s Game, I asked Eugene Fama, “If the costs involved were exactly the same, would you choose an active fund or an index fund?” Without hesitation he said he would opt for the index fund. Why? Because, he said, an index fund provides far more diversification.

It’s true, of course, active management offers the possibility of outperformance. But mathematically, the more heavily concentrated a fund is, the more likely it is to underperform. Another disadvantage of greater concentration is the certainty of increased volatility.

As ANU GANTI from S&P Dow Jones Indices explains, it’s a conundrum that active investors need to grapple with.

Volatility, dispersion, and correlation are elements of what we’ve elsewhere characterised as The Active Manager’s Conundrum. Active managers should prefer:

- Low volatility, which is typically associated with higher returns

- High dispersion, which means a larger payoff for correct stock selections

- High correlation, which reduces the opportunity cost of a concentrated portfolio

The conundrum arises because low volatility, high dispersion, and high correlation almost never occur at the same time.

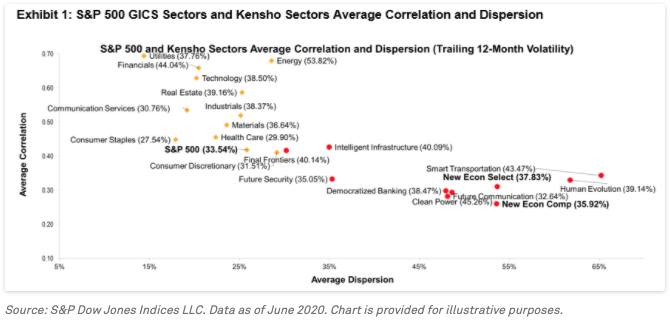

An excellent example of this conundrum lies within the Kensho New Economy Indices. From our Q2 S&P Kensho New Economies Dashboard, Exhibit 1 illustrates that the Kensho sectors have much higher dispersion levels than the traditional S&P 500 GICS sectors. Interestingly, the Kensho sectors also have much lower correlations compared to their S&P 500 counterparts, unsurprisingly given the more idiosyncratic nature of their constituents compared to those within the GICS framework.

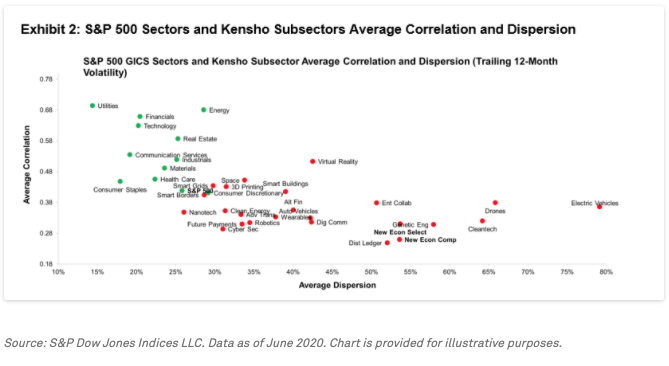

The results are even more striking in Exhibit 2, where we compare the S&P 500 GICS sectors to the Kensho sub-sectors, which have higher dispersion levels along with extremely low correlations.

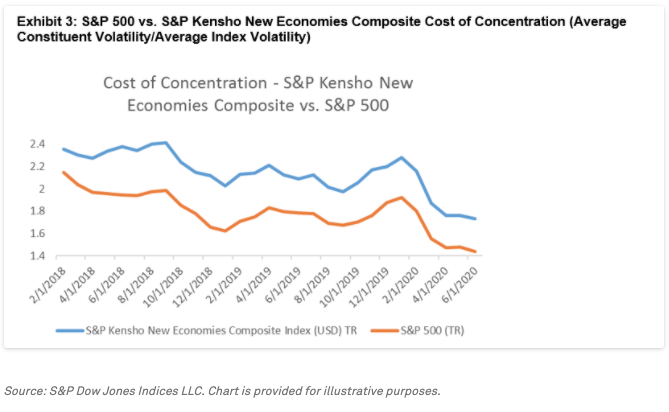

Active managers, almost by definition, run less diversified, more volatile portfolios than their index counterparts. When correlations are high, the incremental volatility associated with being less diversified and more concentrated declines. We define the cost of concentration as the ratio of the average volatility of the component assets to the volatility of a portfolio. A higher cost of concentration implies a higher hurdle for active managers to overcome.

Applying this logic to the Kensho New Economies, we would expect the cost of concentration for the S&P Kensho New Economies Composite to be higher than that of the S&P 500, as its low correlations create the possibility of less incremental portfolio volatility. We observe this to be the case in Exhibit 3, which shows that this cost is consistently higher for Kensho through time.

This analysis has important implications for active management. Because of their high dispersion, there are immense opportunities for stock-pickers to add value by choosing among names in the Kensho New Economy Indices. But doing so requires active portfolios to bear a higher cost of concentration; the low correlation among the New Economies names means that stock-pickers forgo a huge diversification benefit.

Investors who choose active management couple the possibility of higher returns with the certainty of higher volatility.

This article was first published on the Indexology blog. It is republished here with kind permission.

For more valuable insights from our friends at S&P Dow Jones Indices, you might like to read these other recent articles:

How long do top-quartile funds stay there?

Three hundred and twenty billion dollars

US fund managers flopped in the crisis

92% of Canadian fund managers underperformed in 2019

Does adjusting for risk make active performance any better?

How did Australian active managers handle Q1 volatility?

Enjoyed this article? We think you’ll like these too:

Could anyone have predicted Warren Buffett’s success?

Seven simple rules of investing

DC pensions should switch to passive funds — study

Is there a link between intelligence and performance?

Put the odds of success in your favour

Picture: Barth Bailey via Unsplash