There are basically two types of company assets — physical assets such as land, vehicles, equipment and unsold stock, and non-physical assets, usually referred to as intangibles. These include, for example, goodwill, brand recognition and intellectual property. Some, but by no means all, intangible are included on a company’s balance sheet.

Most investment analysts tend to consider intangible assets when assessing whether a particular stock is either under- or over-priced. But what, if anything, do intangible assets tell us about future performance? And what type of intangible assets offer the most clues? A new paper by Savina Rizova and Namiko Saito from DIMENSIONAL FUND ADVISORS provides some answers.

Many companies use intangible assets such as patents, licenses, computer software, branding, and reputation to earn revenues. These intangible assets have always been part of the economic landscape. In our paper, we study the impact of intangibles on our ability to identify differences in expected stock returns and find no tangible performance benefit from adjusting for intangibles.

Two types of intangible assets

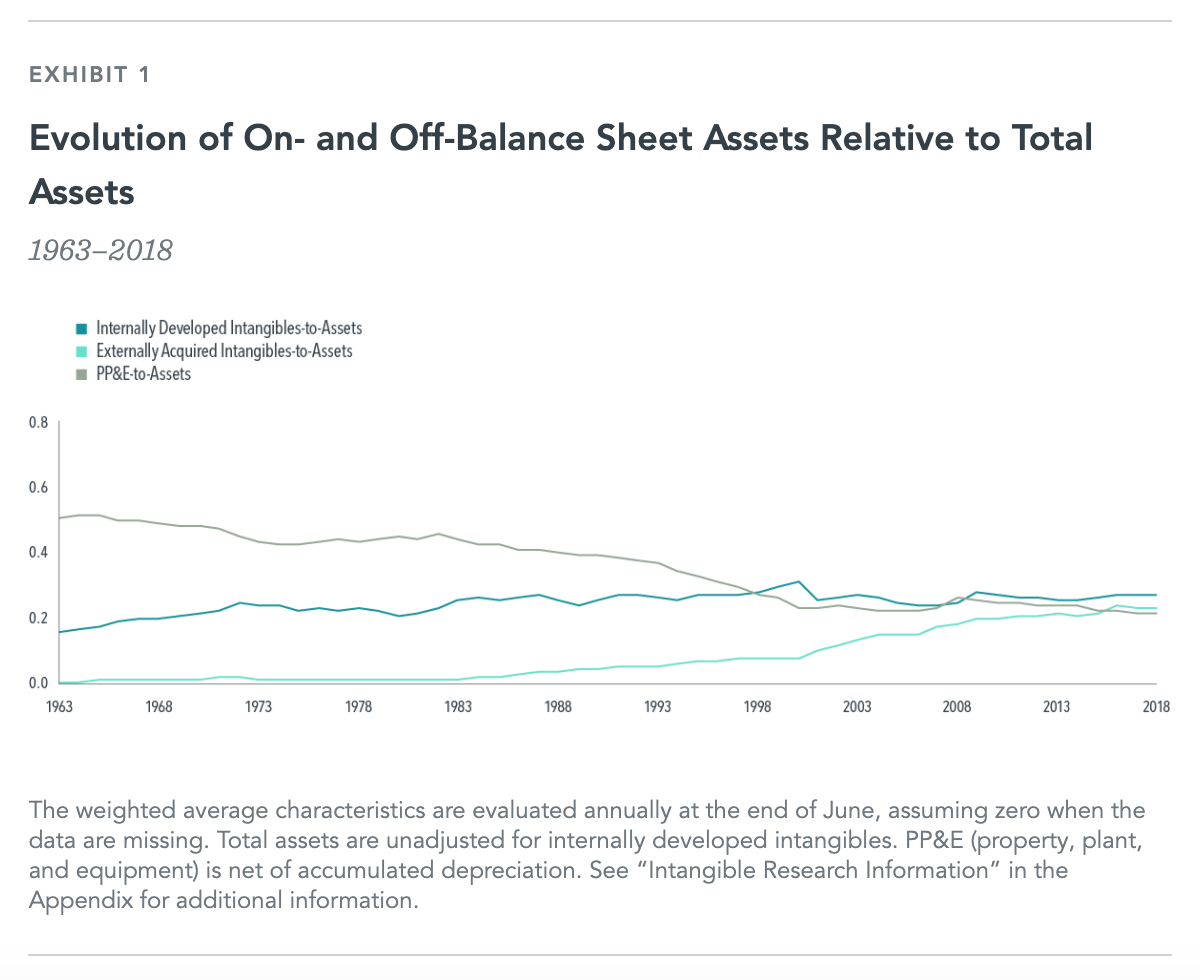

It is important to begin by distinguishing between two types of intangible assets. Under US generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), externally acquired intangibles are reported on the balance sheet. They currently represent about a quarter of the reported value of assets for the average US company. These assets are accounted for when computing book equity.

Internally developed intangibles, on the other hand, are generally not capitalised on the balance sheet. Instead, they are expensed and thus reflected on the income statement. The difference in accounting treatment is primarily due to the higher uncertainty around the potential of internally developed intangibles to provide future benefits and the difficulty to identify and objectively measure such benefits.1 After all, internally developed intangibles do not go through a market assessment, while externally acquired intangibles get evaluated in the competitive market for mergers and acquisitions, and at that time, they might already be generating tangible benefits for the company that developed them. For example, Disney bought the Star Wars franchise, an externally acquired intangible, in 2012, many years after the franchise began generating economic benefits for Lucasfilm.

Some argue that to more effectively infer differences in expected returns across firms sourcing most of their intangibles externally and firms sourcing them mostly internally, we should capitalise internally developed intangibles. Several academic studies do that by accumulating the historical spending on research and development (to capture the development of “knowledge capital”) and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses (to capture the development of “organisational capital”).

In the present study, we follow the approach suggested by Peters and Taylor (2017)2 and find that while intangible assets comprise more of companies’ assets over time, this stems mainly from growth in externally acquired intangibles. Estimated internally developed intangibles have not meaningfully increased as a proportion of total assets (see Exhibit 1).

Moreover, the estimation approach for internally developed intangibles has several important caveats in addition to the lack of market valuations.

First, the estimation of internally developed intangibles assumes that the development of intangible capital can be captured fully through spending reported on the income statement. Second, the approach is critically dependent upon the availability of reliable and comprehensive R&D and SG&A data.

However, we observe R&D data for about half of the US market even today. As a result, the estimated knowledge capital is zero for about half of the US market. Thus, we would adjust the value and profitability metrics of half of the market for knowledge capital and leave the rest unadjusted, potentially making firms in the adjusted and unadjusted groups less comparable, not more, after the adjustments. Further, while SG&A data are available for most US companies since the 1960s, the breakdown of operating expenses into cost of goods sold and SG&A varies often across companies and data sources, which might add noise to the estimation of organisational capital. The estimation approach can also produce noisy results because it applies constant amortisation rates through time and does not allow for impairments. As a result, a company can be approaching bankruptcy and still appear to have billions of dollars’ worth of internally developed intangibles.

Because of all those different sources of noise, capitalising estimated internally developed intangibles might not be helpful in identifying differences in expected stock returns. Our empirical research lends support to this expectation. Estimated internally developed intangibles contain little additional information about future firm cash flows beyond what is contained in current firm cash flows. Moreover, we do not find compelling evidence that capitalising estimated internally developed intangibles yields consistently higher value and profitability premiums.

Conclusion

Given the large challenges with estimating internally developed intangibles, an alternative approach to infer more effectively differences in expected returns among firms with different sources of intangibles might be to strip out externally acquired intangibles from the balance sheet. Our empirical analysis shows no compelling performance benefit of excluding externally acquired intangibles from fundamentals. Historically, the exclusion of externally acquired intangibles would not have generated higher value or profitability premiums.

Therefore, we believe investors are better off continuing to incorporate externally acquired intangibles reported on the balance sheet and not adding noisy estimates of internally developed intangibles to value and profitability metrics.

You can read the full paper here:

Intangibles and expected stock returns

1Financial Accounting Standards Board, “Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 2,” October 1974.

2Ryan H. Peters and Lucian A. Taylor, “Intangible Capital and the Investment-Q Relation,” Journal of Financial Economics 123, no. 2 (February 2017): 251–72.

This article first appeared on the Dimensional Fund Advisors website.

Interested in more insights from Dimensional? Here are some other recent articles from this series:

Should a top-heavy stock market worry us?

Why the disconnect between the economy and markets?

The widening valuation spread between growth and value

What will the recession mean for small-cap stocks?

How worried should investors be about the recession?

Remember, you’ve trained for this