By ROBIN POWELL

I’m told Apple is the most loved brand for people in my age category, closely followed by Amazon and Netflix. But for a brand that’s practically perfect in every way, how can you look past Vanguard?

It ticks virtually every box for me. Transparent. Customer-focused. Mutually owned. And, of course, it’s bringing down the cost of investing for everyone.

“You’re so nice to Vanguard all the time,” a financial adviser once told me. “I assume you’re being paid for all the custom TEBI generates for them?” If only we were.

But is there anything not to like about Vanguard? Finding faults with this company is like looking for reasons to hate Tom Hanks. Does it have any at all?

Actually, yes, it does.

No company’s perfect

I’ve said before that Vanguard could raise its game on the corporate governance front. But a much bigger issue for me is its continued promotion of actively managed funds.

It still surprises many people to learn that, despite its reputation as a pioneer of index funds, Vanguard is one of the largest active fund companies in the world.

The 11 original funds at its inception in 1975 were all actively managed. Indeed, Vanguard’s active roots date back to the founding of the Wellington fund in 1929.

I’m based in the UK, where Vanguard started managing assets in 2011. Here, the focus of Vanguard’s marketing efforts over the last nine years has been on promoting active funds.

I don’t have anything against active management in principle. If you are going to invest in an active fund, you would be wise to invest in one with lower fees. Vanguard’s active funds are considerably cheaper than the industry average.

I also understand that Vanguard is a business, and that the fees generated by each actively managed dollar are far higher than for every indexed dollar. There’s an obvious, and entirely understandable, commercial incentive behind this strategy.

But, in asset management, what’s good for the industry is usually bad for the consumer. Here at TEBI we always like to look at things from the perspective of the investor. So, do Vanguard’s active funds deliver higher net returns than its equivalent index funds?

Vanguard active or Vanguard passive?

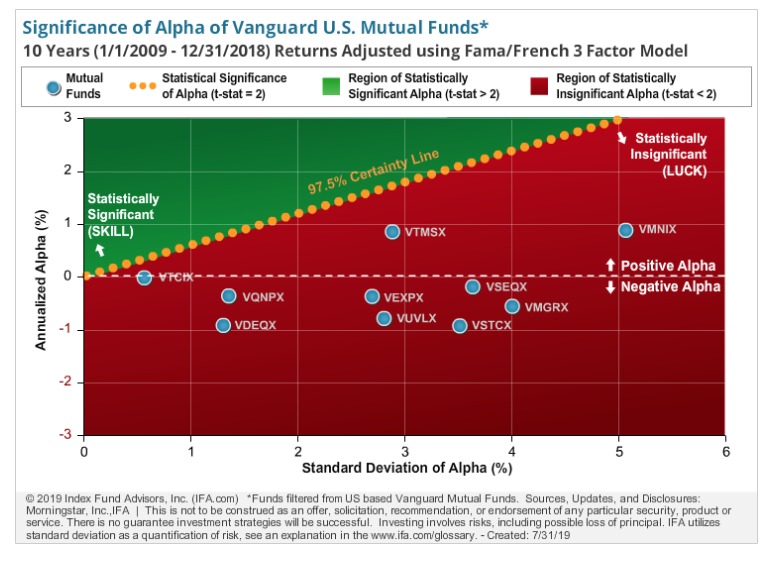

This time last year, Mark Hebner and Murray Coleman from Index Fund Advisors conducted a thorough analysis of Vanguard’s fund performance in the US.

They looked at 57 active funds offered by Vanguard with at least five years of performance data through 2018. They also analysed 17 active funds once managed by Vanguard but which were no longer running in their own right.

As TEBI readers know, such a survivorship rate is not untypical. Funds are often closed down or merged with other funds, usually as a result of poor performance.

This is what they found:

— 36.49% (27 of 74 funds) had underperformed their respective Morningstar benchmarks or did not survive the period since inception.

— 40.54% (30 of 74 funds) had outperformed their respective benchmarks since inception.

— 2.70% (2 of 74 funds) outperformed their respective benchmarks consistently enough since inception to provide 97.5% level of confidence that such outperformance will persist as opposed to being based on random outcomes.

Statistical significance

That third and final finding is is the crucial one. Simply by the law of averages, some funds will always beat the market, even over the long term. If you flip a coin for long enough, sooner or later you’re going to flip ten heads in a row.

If outperformance is genuinely down to skill, there’s a possibility — certainly not a guarantee — that the manager or managers of that fund will be able to outperform again in the future. But luck is not a repeatable skill.

Distinguishing luck from skill in active management is extremely difficult, but the chart below gives an idea as to how statistically significant Vanguard’s outperformance has been.

The more reliable strategy

Hebner and Coleman concluded their research as follows:

“Like many of the other largest financial institutions, a deep analysis into the performance of Vanguard has yielded a not so surprising result: active management is likely to fail many investors.

“We believe this is due to market efficiency, costs and increased competition in the financial services sector.

“As we always like to remind investors, a more reliable investment strategy for capturing the returns of global markets is to buy, hold and rebalance a globally diversified portfolio of index funds.’

A question of probabilities

As always with active management, it will be many years in the future before you know whether you’ve made the right decision. But it all boils down to probabilities.

Of course, you might choose one of that very small percentage of Vanguard funds which do deliver statically significant outperformance.

But the overwhelming likelihood is that, over the long term, you will underperform the equivalent Vanguard index fund.

Or you might be unfortunate enough to pick an active Vanguard fund that performs very poorly.

Not good value

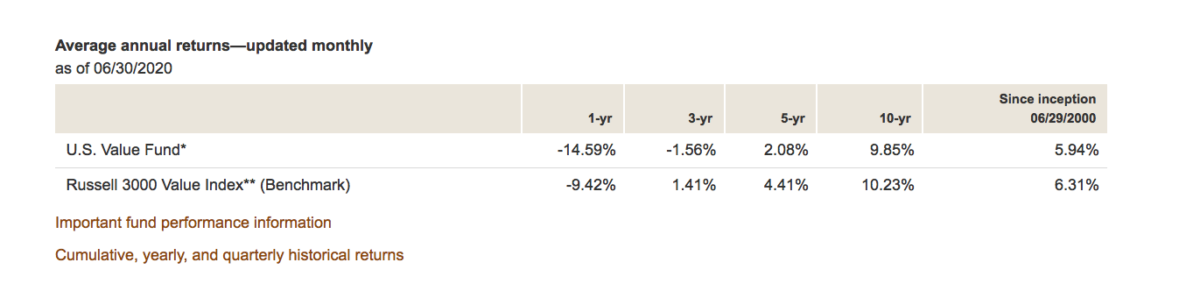

Take the Vanguard US Value fund (VUVLX), for example. Founded in June 2000, the fund went through a number of external managers before being taken over by Vanguard’s in-house quant team.

But the performance of the fund has been consistently dreadful. The last time it beat the benchmark was in 2014.

Daniel Wiener from Adviser Investments describes the fund in InvestmentNews as a “failure” and a “loser”.

“What’s clear,”Wiener says, “is that none of the manager changes enhanced US Value’s performance against the straight-ahead value benchmark.”

You can see from the chart below that the fund has lagged the benchmark in all of the time periods shown. As of the end of June 2020, it had a three-year annualised return of negative 1.56% (compared to a positive return of 1.41% for the index), a five-year annualised return of 2.08% (cf. 4.41% for the index), and a ten-year average of 9.85% (cf. 10.23% for the index).

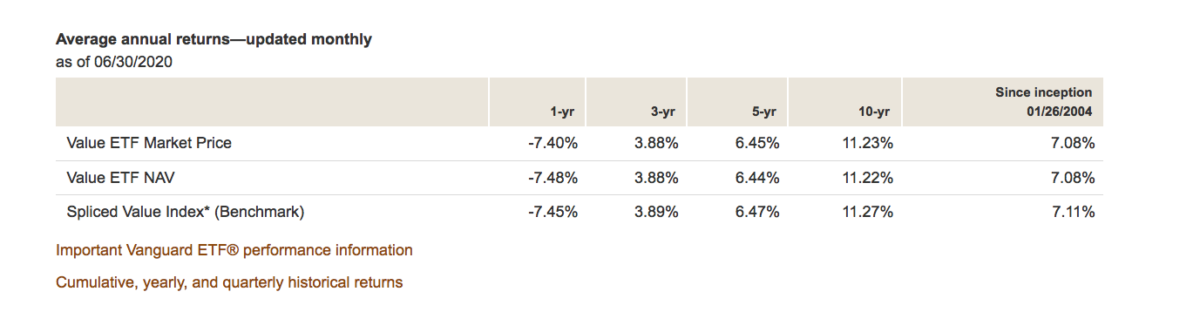

With an annual fee of 22 basis points, the active value fund is considerably more expensive than Vanguard’s equivalent passive funds, and that doesn’t include transaction costs either. The Vanguard Value Index fund costs five basis points and the Vanguard Value ETF (VTV) just four. They passive funds have also produced significantly higher net returns.

The chart below shows the performance of the Vanguard Value ETF over the same time periods. The ETF has a three-year annualised return of negative 3.88%, a five-year annualised return of 6.45%, and a ten-year average of 11.23%.

Now, finally, Vanguard has decided enough is enough. The active value fund is closing to new investors, and the firm is proposing to merge it with the Vanguard Value Index fund.

Significant step

Of course, as a news story, the closure of Vanguard US Value doesn’t even register on the Richter scale. But I do believe it’s significant.

Vanguard devoted considerable energy and resources to this fund since bringing its management in-house. It had an impressive array of PhDs and CFAs working on it. And yet it failed miserably.

Once again, as we’ve come to expect from Vanguard, it’s done the right thing by its clients in closing it.

But will the fund’s demise also make Vanguard management look at the bigger picture?

Can it carry on its policy of heavily promoting low-cost active funds — especially in countries outside the US where most consumers are still completely unaware of the benefits of indexing?

The beginning of the end?

Mark Hebner, one of the authors of the research I referred to earlier, isn’t surprised at the closure of the value fund.

“About five years ago I attended a small Vanguard presentation in Newport Beach,” he recalls. “They actually stated that investors would only have about a 50/50 chance of beating the passive fund. I have always said that due to fees and mistakes, it is actually worse that that.

“I raised my hand and said, I suggest you merge every active fund into its index fund alternative.

“I hope this merger of active into index funds will be the beginning of the end of Vanguard active funds. Alpha is a myth and Vanguard, of all mutual fund companies, should be the first company to accept that and move on to a 100% index funds offering.”

I very much doubt that this is the beginning of the end for Vanguard’s pursuit of alpha. But it should certainly give the company’s management cause for reflection.

You’ve still got a friend in me, Vanguard. But that comparison with everyone’s favourite Hollywood star is going to need some justifying.

Here are some recent articles you may have missed:

Market timers are fooling themselves

Stop admiring your successful trades

Three truths about ESG investing

Hedge fund fees are much worse than you thought

Should you invest with Baillie Gifford?

Is there such a thing as a “normal” stock market?

Active or passive — which is more volatile?

© The Evidence-Based Investor