A cautionary tale about chasing performance

Comments Off on A cautionary tale about chasing performance

By LARRY SWEDROE

My 2007 book Wise Investing Made Simple: Larry Swedroe’s Tales to Enrich Your Future contained 27 tales whose goal was to educate investors about important investment concepts and strategies. This article is in the spirit of those tales.

That’s what diversification is for. It’s an explicit recognition of ignorance.

— Peter Bernstein

In early January 1993, Ryan received a letter informing him that he had just inherited $1million from his grandfather, who had recently passed away. He now had to determine how to invest the funds.

Ryan met with a friend who was a finance professor to seek his advice. The professor told him that new academic research had found that, historically, small-value stocks had outperformed the S&P 500 by about three percent a year. The professor explained that the excess return was not a free lunch. Those small-value stocks were a lot riskier, with volatility that was about 35 percent greater than that of the S&P 500. There were also some multiyear periods over which small-value stocks dramatically underperformed.

The professor recommended he read the literature so he could understand the risks. He went on to add that if Ryan could remain disciplined, living through those periods when small-value stocks underperformed without abandoning the strategy, it was likely he would be rewarded.

Ryan liked the idea of trying to outperform the market. He felt he could take the risks of owning those riskier small-value stocks because he had a stable job and no debt. With that in mind, he went to the library and read Eugene Fama and Kenneth French’s 1992 study The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns, which provided the historical evidence on the existence of both a small stock and a value stock premium. He was convinced. He called the professor and asked him for advice on implementing the strategy of investing in small stocks.

The professor told him that, fortunately, there was a relatively unknown company that had employed both of the authors of the paper he had read, and they were about to launch a U.S. small-value fund that would invest based on the research. Because the fund would not be engaged in any individual stock selection, nor any market timing, the fund’s expenses would be relatively low. The fund was called the DFA U.S. Small Cap Value Fund (DFSVX).

How did things turn out?

Ryan was one of the first investors when the fund launched in March 1993. Fast forward to the end of 1999. Since inception, the fund had performed well in absolute terms, providing a return of 14.3 percent per year.

However, it lagged the performance of Vanguard’s 500 Index Fund (VFINX) by more than 7 percentage points a year. Ryan was very disappointed. He had been invested for almost seven years, and he was way behind where he could have been had he simply invested in VFINX. He was also reading and hearing about the “death of value” and how this was a new era dominated by high-tech growth firms. He decided enough was enough, and he sold his shares in DFSVX and bought VFINX.

Seven years later

Fast forward seven more years to the end of 2006. Ryan again reviewed his performance. While VFINX had performed very poorly, earning just one percent a year and underperforming the return on his FDIC-insured certificates of deposit at the local bank, the fund he sold, DFSVX, had earned 18 percent a year.

Ryan was regretting his decision. He recalled the professor’s advice about making sure he stayed disciplined through periods of underperformance. He should have ignored those stories about a new era. Ryan decided he had made a mistake in too quickly abandoning the idea that small-value stocks were likely to outperform. He wanted to do what smart people do: when they make a mistake, they admit it. He could do that. So he sold his shares in VFINX and bought back DFSVX.

Another 12 years on

Fast forward 12 years to the end of 2016. In reviewing the performance of DFSVX, he found it had provided exactly the same 6.8 percent return as VFINX had. While disappointed that DFSVX had not outperformed, at least it had not underperformed. On the other hand, he had taken more risk — risk which had gone unrewarded. Not wanting to repeat his earlier mistake of abandoning small-value stocks too soon, he decided to stay the course.

April 2020

Fast forward to April 2020, right after the COVID-19 crisis had hit the market. Reviewing performance, Ryan found that DFSVX had actually lost almost 8 percent a year while VFINX had returned more than 10 percent a year. Ryan was at a loss. He did not know what to do. How could he have been so wrong on each decision?

Ryan called Chuck, his CPA, and asked him if he would recommend a good investment adviser. Chuck recommended that Ryan meet with Steve, a registered investment adviser (RIA) whom he had been working with for a long time. Ryan called and set up a meeting.

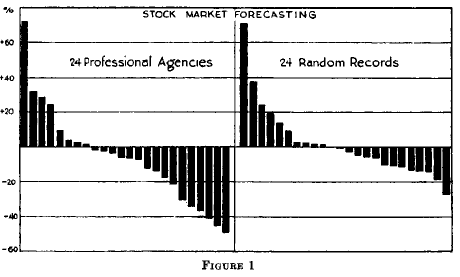

After a brief introduction, Steve asked Ryan to describe his investment experiences. After hearing the tale of woe, Steve explained that if Ryan was looking for an adviser who could shift allocations and persistently deliver superior returns by doing so, he was talking to the wrong person. Steve explained that evidence demonstrated that doing that is a “loser’s game” — one that is possible to win but the odds are so poor that it isn’t prudent to try.

Steve went on to explain that Ryan’s poor performance was caused by making behavioural errors common to most investors — errors made because they have neither the sufficient education in financial theory nor the knowledge of investment history that are needed to play what he called the “winner’s game”.

Recency bias

Ryan had made the mistake of recency bias, extrapolating recent performance into the future as if it were preordained. That led him to buy after periods of good performance (when prices were high and thus expected returns were low) and sell after periods of poor performance (when prices were low and thus expected returns were high). Buying high and selling low is not exactly a prescription for investment success.

Let’s take a look at how Ryan would have done if he had bought either VFINX or DFSVX and simply held on to them. To keep the example simple, we’ll ignore the impact of taxes incurred along the way through dividends, distributions, and capital gains taxes incurred when selling a fund. This would be the case if the money was invested in a retirement plan.

The $1 million he originally invested would have turned into about $11.6 million had he bought and held DFSVX, and about $11 million had he bought and held VFINX. Instead, chasing recent past performance led to an ending value of about $3.4 million. In other words, sticking with one’s asset allocation is far more important than choosing the “right” one.

The prudent strategy

Because we cannot know the future (all investment crystal balls are cloudy), the prudent strategy is both diversification and disciplined rebalancing. For example, a portfolio that was split equally between DFSVX and VFINX and rebalanced annually would have had an ending value of about $12 million, outperforming each of the components.

As homework, Steve gave Ryan a copy of Investment Mistakes Even Smart Investors Make and How to Avoid Them, which discusses 77 mistakes made by investors due to ignorance or behavioral errors. Among the 77 mistakes is recency.

Steve then went on to explain his firm’s investment philosophy, which was based on the academic research and not on opinions. He explained that investment strategy should be based on the following few core principles. First, the market is highly, though not perfectly, efficient. Second, it therefore follows that all risky assets should have similar risk-adjusted returns (including accounting for the risk of illiquidity). Third, it then follows that you should diversify your portfolio across as many unique sources of risk that meet the criteria established in Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing — persistence, pervasiveness, robustness, implementability and intuitiveness.

Risk and uncertainty

Steve then explained that the reason we want to diversify across many independent sources of risk is that we live in a world of uncertainty.

There is an important distinction between uncertainty and risk; they are not the same thing. Risk exists when probabilities are known. For example, when we roll the dice, we can precisely calculate the odds of any outcome. And using actuarial tables, we can calculate the odds of a 65-year old living beyond age 85. Uncertainty exists when we cannot calculate the odds. An example would be the uncertainty of another attack like the one we experienced on September 11, 2001. How should investors address the issue of uncertainty? Steve explained: “The safest port in a sea of uncertainty is diversification.”

Steve noted that Paul Samuelson, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, had summarised his thoughts on diversification:

“I’m a big believer in diversification, because I am totally convinced that forecasts will be wrong. Diversification is the guiding principle. That’s the only way you can live through the hard times. It’s going to cost you in the short run, because not everything will be going through the roof.”

Steve next explained that while diversification has been called “the only free lunch in investing”, it doesn’t eliminate the risk of losses. Diversification does require accepting the fact that parts of your portfolio will behave entirely differently than the portfolio itself and may underperform a broad market index, such as the S&P 500, for a very long time. In fact, a wise person once said that if some part of your portfolio isn’t performing poorly, you are not properly diversified. The result is that diversification is hard.

Resulting

Steve went on to explain that another error Ryan made, one commonly made by investors, was the tendency to equate the quality of a decision with the quality of its outcome. Poker players call this trait “resulting”.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Fooled by Randomness, provided this insight into the right way to think about outcomes:

“One cannot judge a performance in any given field by the results, but by the costs of the alternative (i.e., if history played out in a different way). Such substitute courses of events are called alternative histories. Clearly the quality of a decision cannot be solely judged based on its outcome, but such a point seems to be voiced only by people who fail (those who succeed attribute their success to the quality of their decision).”

In my book Investment Mistakes Even Smart Investors Make and How to Avoid Them, this mistake is called “confusing before-the-fact strategy with after-the-fact outcome”. The mistake is often caused by “hindsight bias”: the tendency, after an outcome is known, to see it as virtually inevitable.

As John Stepek, author of The Sceptical Investor, advised:

“To avoid such mistakes, you must accept that you can neither know the future, nor control it. Thus, the key to investing well is to make good decisions in the face of uncertainty, based on a strong understanding of your goals and a strong understanding of the tools available to help you achieve those goals.

“A single good decision can lead to a bad outcome. And a single bad decision may lead to a good outcome. But the making of many good decisions, over time, should compound into a better outcome than making a series of bad decisions. Making good decisions is mostly about putting distance between your gut and your investment choices.”

Steve emphasised the importance of learning that good decisions can lead to bad outcomes. In his 2001 Harvard commencement address, Robert Rubin, former co-chairman of the board at Goldman Sachs and Secretary of the Treasury during the Clinton administration, addressed the issue of resulting.

Rubin explained:

“Individual decisions can be badly thought through, and yet be successful, or exceedingly well thought through, but be unsuccessful, because the recognised possibility of failure in fact occurs. But over time, more thoughtful decision-making will lead to better results, and more thoughtful decision-making can be encouraged by evaluating decisions on how well they were made rather than on outcome.”

Unfortunately, as Ken Fisher and Meir Statman noted in their 1992 paper A Behavioral Framework for Time Diversification: “Three years of losses often turn investors with thirty-year horizons into investors with three-year horizons: they want out.” This results in the opposite of what a disciplined investor should be doing: rebalancing to maintain their portfolio’s asset allocation.

Ten years is likely noise

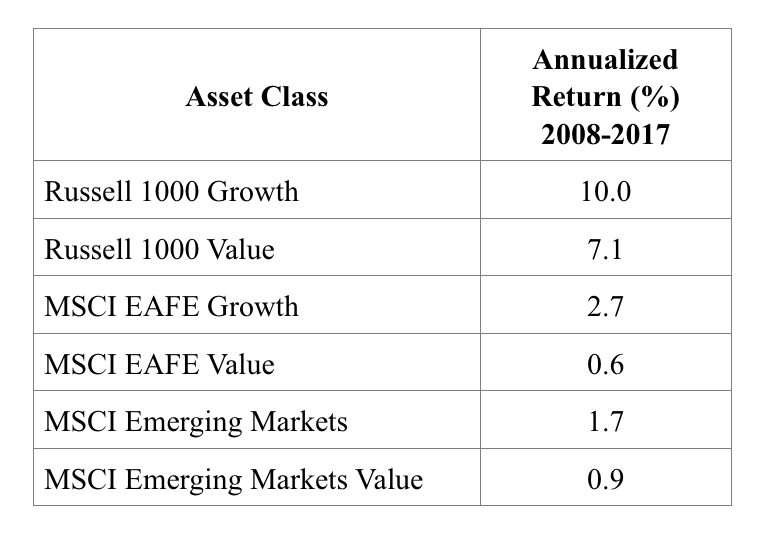

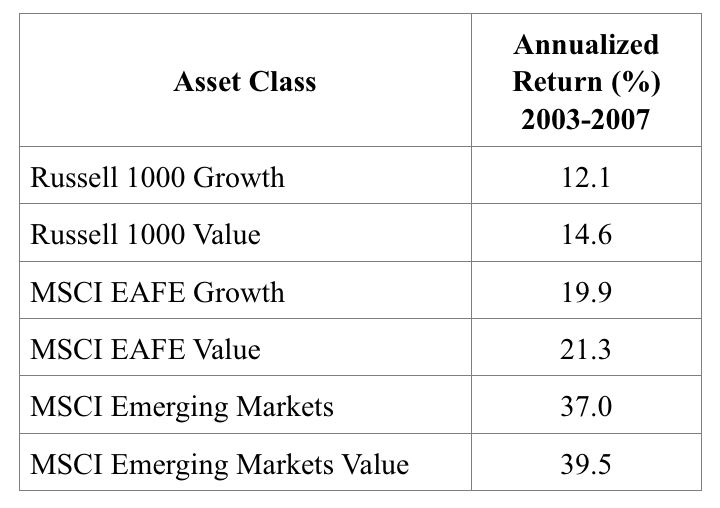

Steve then showed Ryan the following dramatic examples of underperformance, which demonstrate that even ten years is likely noise when it comes to risk assets.

- Over the 40-year period 1969-2008, long-term Treasury bonds outperformed both U.S. large-cap and small-cap growth stocks. Showing the benefits of diversification, while the long-term Treasury bond returned 8.9 percent per year, the Fama-French (FF) Large Value Research Index outperformed by 2.7 percentage points per year, and the FF Small Value Research Index outperformed by 5.6 percentage points per year (over 40 years!).

- Over the 19-year period 1929-47, the S&P 500 Index underperformed five-year Treasuries. Showing the benefits of diversification, while the S&P 500 Index returned 3.0 percent per year, the FF Small Cap Value Research Index outperformed by 5.1 percentage points per year.

- The S&P 500 Index also underperformed five-year Treasuries over the two 17-year periods 1966-82 and 2000-16. Again showing the benefits of diversification, from 1966 through 1982, while the S&P 500 Index returned 6.8 percent per year, the FF Small Value Research Index outperformed by 10.1 percentage points per year. And from 2000 through 2016, while the S&P 500 Index returned 4.5 percent per year, the FF Small Value Research Index outperformed by 8.0 percentage points per year.

These examples will help you avoid the mistakes of recency and resulting. That said, it is always a good idea to be a sceptical investor. Thus, there is nothing wrong with questioning a strategy after a long period of underperformance. With that in mind, you should ask if any of the assumptions behind the strategy are no longer valid. Or did the risks just happen to show up? Seek the truth, whether it aligns with your beliefs or not.

Where the truth lies

For investors, the truth lies in the data on persistence, pervasiveness, robustness, implementability and, importantly, intuitiveness of the premium — the reason we should expect it to persist. For example, the three periods of at least 17 years when the S&P 500 underperformed five-year Treasuries should not have convinced you that U.S. stocks should no longer be expected to outperform the far less risky five-year Treasury note because stocks are riskier than five-year Treasuries. It’s just that sometimes the risks show up.

And that brings us to another mistake I can help you avoid: the mistake of thinking that when it comes to investments in risky assets, three years is a long time to judge performance, five years a very long time, and 10 years is too long. Financial economists know that when it comes to the performance of risk assets, 10 years is likely to be what they call “noise”, or a random outcome that should be expected to occur but you cannot predict when.

Ryan left feeling that he had found an adviser who would help him find the strategy most likely to allow him to achieve his goals.

The moral of the tale

Recognising that there is no crystal ball allowing us to see which asset classes or sources of risk and return will outperform in the future, the prudent strategy is to diversify across as many of them as we can identify that meet the aforementioned criteria, creating more of a “risk parity” portfolio — one whose risk is not dominated by a single source of risk and return.

Unfortunately, that is the case with the traditional 60 percent equity/40 percent bond portfolio, where the vast majority of risk is concentrated in market beta, typically 85 percent or more (because the equities are much riskier than the safe bonds). And the problem of risk concentration is often compounded by home country bias (leading to vastly underweighting international equities).

To help you stay disciplined and avoid the consequences of recency, I offer the following suggestion. Whenever you are tempted to abandon your well-thought-out investment plan because of poor recent performance, ask yourself this question: Having originally purchased and owned this asset when valuations were higher and expected returns were lower, does it make sense to now sell the same asset when valuations are currently much lower and expected returns are now much higher?

The answer should be obvious. If that’s not sufficient, remember Buffett’s advice to never engage in market timing. But if you cannot resist the temptation, you should buy when others panic.

Important Disclosure: Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of actual portfolios nor do indices represent results of actual trading. Information from sources deemed reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Performance is historical and does not guarantee future results. Total return includes reinvestment of dividends and capital gains. In addition, my firm recommends Dimensional Fund Advisors funds to clients.

LARRY SWEDROE is Chief Research Officer at Buckingham Strategic Wealth and the author of numerous books on investing.

Want to read more of Larry’s insights? Here are his most recent articles published on TEBI:

A strategic approach to rebalancing

The cost of anticipating corrections

Markets are more efficient than you think

More proof that consultants can’t pick winning funds

Active fund performance in the COVID crisis

Hedge fund fees are much worse than you thought

OUR STRATEGIC PARTNERS

Content such as this would not be possible without the support of our strategic partners, to whom we are very grateful.

We have three partners in the UK:

Bloomsbury Wealth, a London-based financial planning firm;

Sparrows Capital, which manages assets for family offices and institutions and also provides model portfolios to advice firms; and

OpenMoney, which offers access to financial advice and low-cost portfolios to ordinary investors.

We also have a strategic partner in Ireland:

PFP Financial Services, a financial planning firm in Dublin.

We are currently seeking strategic partnerships in North America and Australasia with firms that share our evidence-based and client-focused philosophy. If you’re interested in finding out more, do get in touch.

FIND AN ADVISER

Are you looking for an evidence-based financial adviser? We can help you find one. Click here for more details.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXX