Critics of indexing have often pointed to the index effect as an example of how passive investing distorts market pricing. But detailed new analysis of the S&P 500 suggests that the index effect appears to be in a structural decline.

Index funds, or at least the market-cap-weighted variety, are simply supposed to replicate the market. But critics of passive investing have long argued that instead of simply reflecting the market, indexing is in some way distorting the market. An example is what’s called the index effect.

The index effect refers to the excess returns putatively associated with a security being added to, or removed from, a headline index. Although it has been studied for decades, the index effect has received more attention in recent years amid the growth of passive investing and the accompanying speculation that stock returns may be affected by buying and selling pressures from index-tracking investors reacting to changes in index membership.

A new paper from S&P Dow Jones Indices analyses the stocks that have been added to and deleted from S&P 500 from the start of 1995 to June 2021. It focuses on the S&P 500, which is the world’s most widely followed index; USD 13.5 trillion was indexed or benchmarked to the large-cap US equity gauge at the end of 20201. If the growth of passive investing contributed to an index effect, you would expect it to appear in S&P 500 additions and deletions.

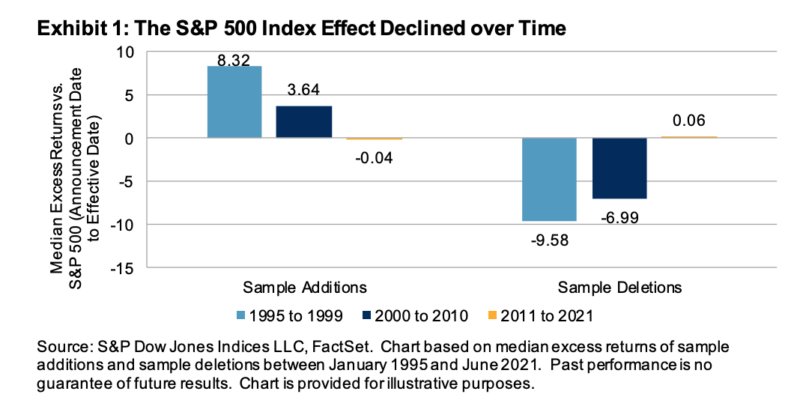

Overall, the study corroborates the general consensus reflected in existing literature: the S&P 500 index effect seems to be in a structural decline (see Exhibit 1). The analysis also suggests that an improvement in stock liquidity may help to explain the attenuation in the index effect over time.

If it is indeed the case that the index effect is in decline, then it means another door is closing on active managers trying to eke out elusive alpha fro global stock markets. “Front-running” the index used to be a way for managers to steal a march on passive investors. Stocks that are selected for the index traditionally go up in price on entering the index. So you could make a profit by buying the stocks before they actually joined the index — i.e. cheaper than index funds could buy the stocks themselves. It’s a perfectly legal and a legitimate strategy. But does it still work? And if so, for how much longer?

Download the paper here:

What Happened to the Index Effect? A Look at Three Decades of S&P 500 Adds and Drops

MORE FROM S&PDJI

For more valuable insights from our friends at S&P Dow Jones Indices, you might like to read these other recent articles, or visit the Indexology blog:

Indexing has saved Americans $357 billion since 1996

Has size contributed to value’s recent revival?

What does history tell us about the value rally?

The case for tracking the venerable Dow Jones

A diverse portfolio is a strong portfolio

Why even Buffett has been buffeted by the index

PREVIOUSLY ON TEBI

What does salience theory tell us about stock returns?

Why do councils waste so much money on pensions?

Do institutional asset managers possess skill?

Don’t let your investments go the way of the CD

Reviewers wanted for Robin Powell’s new book

Leveraged ETFs: another product for the junk pile

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXI