Genuine active management requires confidence and conviction. After all, you’re making an active bet against the collective wisdom of the entire market.

Of course, you could get it right; but, once you take into account the fees you charge and the trading costs you incur, the odds of outperforming the index in the long term are heavily stacked against you.

And there’s another problem. As CRAIG LAZZARA from S&P Dow Jones Indices explains, confidence and conviction on their own are not enough. Active managers also need a degree of courage which many of them simply don’t possess.

Philosophers have long argued that courage is the most essential human virtue, because without courage, all other virtues lie in jeopardy. Remarkably, the theorising of ethicists has an implication for practical portfolio management.

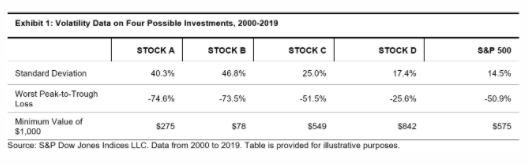

We can illustrate this with a simple example in Exhibit 1. It’s December 31, 1999, and a professional investor is considering buying four different stocks for his clients’ portfolios. He obtains (never mind how; read the paper) correct data on the future volatility of the four candidates. All four possible purchases are more volatile than the market as a whole, but stocks A and B appear especially so.

Owning A and B will be uncomfortable

Our investor has confidence in the analysts who recommended all four investments, and realises that volatility is the price you sometimes must pay to earn the stock market’s long-run returns. But he’s also mindful that positions in stocks A and B, in particular, might produce some very uncomfortable client meetings.

When the $1,000 he invested in stock A is worth only $275, will he still have confidence in his analyst’s recommendation? More urgently, will his clients still have confidence in him? The volatility data make it clear that, regardless of the long-run outcome, stocks C and D will be much more comfortable holdings than A and B.

A is apple, B is Amazon

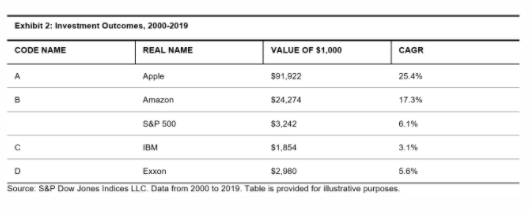

And this, as Exhibit 2 makes clear, is the problem. Stock A is Apple, which turned out to be the best performer in the S&P 500® for the 20 years ended December 2019. Stock B is Amazon, which lagged Apple but still beat the market handily. Stocks C and D, the comfortable choices, both underperformed the S&P 500.

Pity our poor manager: the stocks that would have been easy to hold, and make for relatively stress-free client meetings, ultimately underperformed. The two winners, which would surely have enhanced his reputation as an astute stock picker, would have done the opposite.

Anyone conversant with our SPIVA® scorecards will realise that the average active manager fails most of the time. Why should this be? Active managers are smart, hard-working, well-trained, and highly motivated; the qualities that typically lead to success seem to avail relatively little. We have previously enumerated some of the reasons for active failure — for example, the professionalisation of investment management, or the skewness of equity market returns. The simple example here adds another challenge to this list.

The correct choice may not be the easy choice

One of the reasons why active management is so difficult is that the correct investment choice may not be the easy choice. The challenge for an active manager is not limited to identifying the relatively small number of long-term winners. Success also requires holding the long-term winners when they go through painful periods of short-term underperformance.

Conviction and confidence are not enough to win the day — courage is also needed, and most needed precisely when it’s hardest to muster.

CRAIG LAZZARA is Managing Director and Global Head of Index Investment Strategy at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

This article was first published on the Indexology blog.

For more valuable insights from our friends at S&P Dow Jones Indices, you might like to read these other recent articles:

Active or passive — which is more volatile?

How long do top-quartile funds stay there?

Three hundred and twenty billion dollars

US fund managers flopped in the crisis

92% of Canadian fund managers underperformed in 2019

Does adjusting for risk make active performance any better?

How did Australian active managers handle Q1 volatility?

What are you going to read next? Here are some suggestions:

Practitioners still pay too little attention to academia

Investing shouldn’t be a gamble

Are you still playing by the old rules?

The best friend investors have ever heard of

Do you think you’re smarter than Terry Smith?

Picture: Muzammil Soorma via Unsplash