How will a strengthening dollar affect emerging markets?

- Robin Powell

- Dec 9, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2024

The US dollar has been strengthening, and commentators are predicting that it will strengthen further. The Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates, and higher rates are generally seen as a boon to the greenback, because they increase its attractiveness against other currencies. Another big factor is the long-awaited tapering of the Fed's quantitative easing programme. So what will tapering mean for emerging stock markets? BENEDEK VÖRÖS from S&P Dow Jones Indices has been looking at what happened when then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke revealed plans to taper QE in 2013, and what, if anything, that tells us about the likely impact on emerging markets this time.

When John Connally uttered the famous words above 50 years ago at a meeting of major finance ministers in Rome, it was just three months after the U.S. had unilaterally dismantled the post-World War II global monetary system known as Bretton Woods. The “problem” Connally referred to was a rapidly depreciating U.S. dollar, which threatened the competitiveness of exporters based in the U.S.’s main trading partners.

In the decades since, however, developing countries have faced the opposite challenge. Time and again, a bout of U.S. dollar strengthening has triggered turmoil in emerging economies that predominantly borrow abroad in foreign currencies, usually U.S. dollars. Thus, a strengthening U.S. dollar has increased emerging markets’ debt burden, depressing consumption and economic growth, and consequently leading to dismal domestic equity market returns.

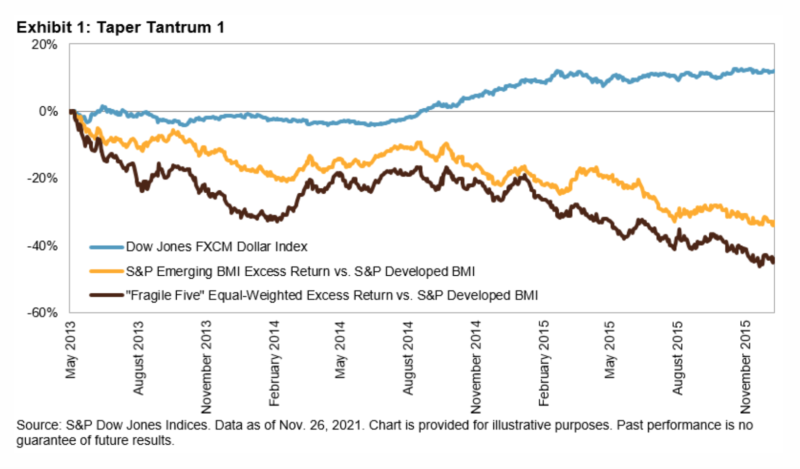

The last such instance was triggered in May 2013, when then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke revealed plans to wind down the Fed’s gargantuan quantitative easing program, setting off a so-called “taper tantrum”: bond yields surged around the world, ex-U.S. stock prices tumbled, and a soaring greenback put severe strain on emerging market economies worldwide. Between May 2013 and December 2015, the S&P Emerging BMI dropped 16% in U.S. dollar terms, underperforming the S&P Developed BMI by 33%. A “Fragile Five” composed of Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia, India, and South Africa were particularly hard hit, underperforming by an average of 44% against the S&P Developed BMI.

What made the “Fragile Five” particularly vulnerable? Factors included low foreign exchange reserves as a percentage of their external debt, and high current account deficits as a percentage of their GDP. Having perhaps learned their lessons, four out of the five have since made significant economic readjustments: India and South Africa swung from a current account deficit to a surplus, while Indonesia and Brazil cut their deficit by 87% and 49%, respectively. Turkey, on the other hand, remains highly vulnerable as the current account deficit barely budged, while the country’s FX reserves plummeted by 36% as a percentage of total external debt between the end of 2013 and 2020. India also increased its FX reserves significantly, from 70% to 105% of total external debt, while South Africa, Indonesia, and Brazil registered moderate decreases between 8%-14%.

As the Fed gets ready yet again to “taper”, the U.S. dollar has entered another round of strengthening. Since the start of June 2021, the Dow Jones FXCM Dollar Index, which is designed to measure the broad performance of the U.S. dollar against four developed market currencies, has risen 4%. Emerging market equities have also come under pressure, but a few of the former “Fragile Five” have fared considerably better than last time, particularly India. Since June 2021, the S&P India BMI is up 10%, compared to a 14% decline in the S&P Turkey BMI.

International allocators may be wise to heed the Greek historian Thucydides and distinguish between those currency regions well-positioned to weather the storm, and those more at risk from a rise in the dollar: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.