Is higher inflation always bad news for stocks?

- Robin Powell

- Feb 7, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: May 26, 2025

My September 11, 2023, Advisor Perspectives article reviewed the empirical research findings on the relationship between inflation, corporate profits and stock returns, demonstrating that over 10-year periods and even longer, equities have not provided a strong inflation hedge. They have tended to suffer from a less-stable economic climate (the rate at which future earnings are discounted rises, lowering valuations), and costs have tended to rise with inflation more than output prices. The research has also found that despite the poor performance of equities in high and rising inflationary regimes, equities have historically benefited from rising inflation when the starting level was below the median (when there was risk of deflation) but were hurt by rising inflation if the starting level was above the median (when there was increased risk of escalating inflation).

Latest research

In their 2023 study, Factoring in Inflation, Andrew Berkin and Cindy Griffin of Bridgeway Capital Management examined how stocks have performed historically in different inflationary environments and compared them to the asset classes of bonds and cash. They began by noting that while the CRSP 1-10 Index (U.S. total stock market) lost 19.8% in 2022 when the CPI rose 6.5%, it returned 24% in 2021 when the CPI increased by an even greater 7.0%. Following is a summary of their key findings:

While higher inflation resulted in higher interest rates (and lower bond returns), there was no distinct relation with stock returns. For example, interest rates could rise because of a strong economy, which should bring higher earnings and cash flows.

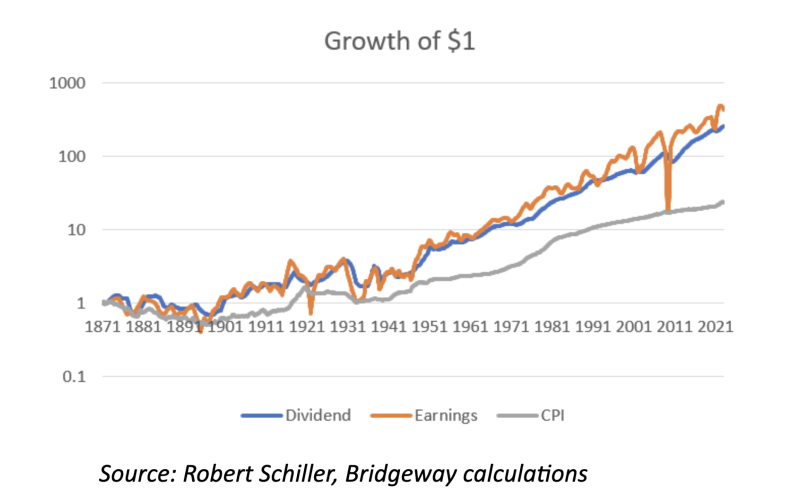

Over the period 1871-2022, earnings and dividend growth tracked inflation, though at a higher level, allowing investors to participate in the growth of the economy – and nominal growth has typically been higher than inflation.

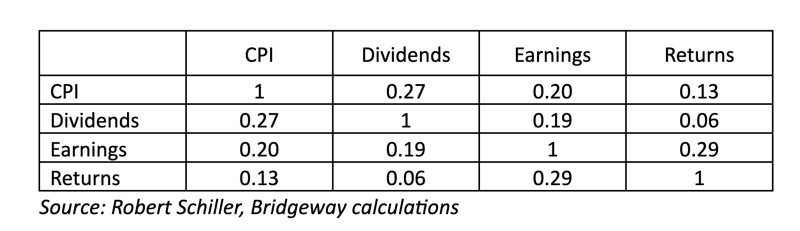

Over the period 1871-2022, the annual correlation of inflation, earnings, dividends and stock returns was only modestly positive. Thus, stocks provided only a modest hedge to inflation at an annual level. The reason the correlation was not stronger is that other factors were at play, as the market is forward-looking and moves to perceptions of future cash flows and discount rates, not just inflation.

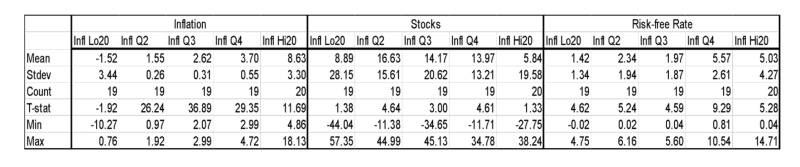

Over the period 1927-2022, stock returns were consistently positive in each of the quintile inflationary regimes. But there was great fluctuation (high standard deviations and high spreads of the minimum and maximum returns). Returns were highest and statistically significant for the middle three inflationary quintiles. But returns were not as strong on average when inflation was low or negative.

While stock returns were on average positive (5.84%) in the highest inflation regimes, and stocks outperformed cash, the real return was on average negative (-2.79%). In the other inflationary regimes, the returns to stocks in real terms was highly positive – at least 10%.

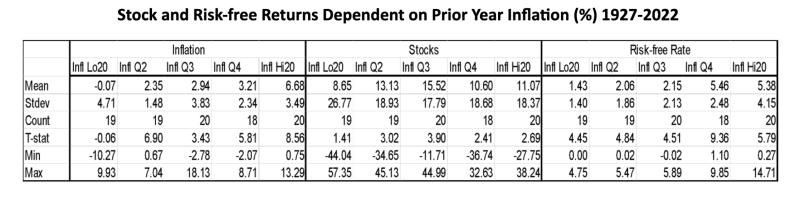

Inflation was sticky; high or low inflation in one year tended to be repeated the next year. But it was not guaranteed.

Examining stock and risk-free returns dependent on the prior year’s inflation rate, over the period 1927-2022 after a year of high inflation, stocks tended to do quite well, with an average return of 11.07% – on par with the returns of the other quintiles as well as the long-term average of 11.84%.

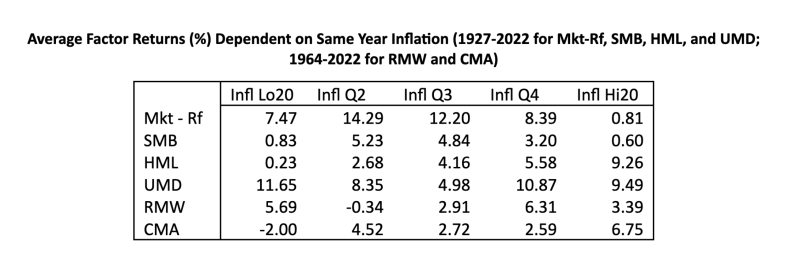

Examining how different factors performed in different inflationary environments (grouped by quintile), while on average the size (SMB), value (HML) and momentum (UMD) factors always provided a premium, the profitability (RMW) and investment (CMA) factors each produced a negative premium in one quintile. But there was no clear pattern (and there was wide variation, ›not shown in the table) with one notable exception – value, which produced higher premiums the higher the inflationary quintile.

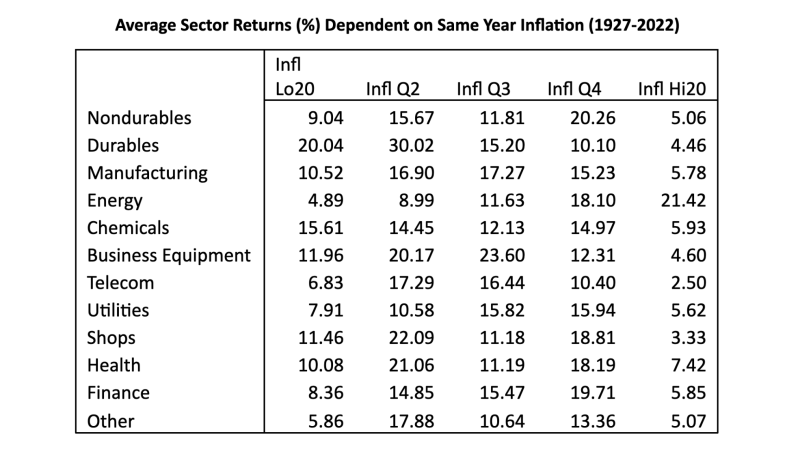

Examining returns by sector, while returns were lowest in the low and high inflation quintiles, there was again little noticeable pattern, with the exception of energy – returns rose monotonically with inflation, climbing from 4.89% on average in the low inflation quintile to 21.42% when inflation was high.

Berkin and Griffin then examined the relationship between inflation and stock returns in 21 developed market countries and found similar patterns to those in the U.S.

In 17 out of 21 countries, stocks failed to beat inflation when it was high.

Most of the four countries where stock returns were higher are known for having a large amount of their economy dependent on commodities, which like energy can rise with or cause inflation.

In none of the countries did cash or bond returns keep pace with high inflation.

In almost all countries, stocks were the best asset class when inflation was high. The only exceptions were Norway and Spain, where bills were best in high inflation; and Switzerland, where both bills and bonds beat stocks in high inflation regimes.

For the full set of 21 developed markets over 123 years, stocks were clearly the highest-returning asset class on average when inflation reared its head.

Their findings led Berkin and Griffin to conclude: “Higher inflation isn’t always bad news for stocks, and it can affect the performance of different factors quite differently. And even when high inflation dampens equity returns, stocks still produce positive returns on average during high inflationary periods – and strongly outperform cash. These results suggest that investors who let fears of high inflation drive them out of the stock market could be making a costly mistake.”

Investor takeaways

While the stock market’s poor performance in 2022 led many investors to think that high inflation automatically means bad news for stocks, the empirical evidence shows that has not always been the case. Equity markets around the globe have generally outperformed cash during high inflation regimes, suggesting that allowing fears of an inflationary environment to drive investment decisions out of stocks and into cash or bonds could be a very costly mistake.

Investors should approach these results with caution because, while the average return of stocks in high inflation environments has been positive, the variation of returns from year to year can be large (one can drown in a river with an average depth of six inches). An investor’s experience in one year can be very different in another.

While many investors believe that equities provide protection from inflation (a firm’s debt obligations are inflated away, and product prices may be adjusted to inflation), over 10-year periods and even longer, equities have not provided a strong inflation hedge. They have tended to suffer from a less stable economic climate (the rate at which future earnings are discounted rises, lowering valuations), and costs have tended to rise with inflation more than output prices. At the same time though, the evidence demonstrates that if you pull out of stocks because inflation is high, you risk missing out on the subsequent strong performance of stocks in the following year. Thus, having a well-thought-out plan that incorporates uncertainty and adhering to it, rebalancing along the way, is the strategy that most likely will allow you to achieve your financial goals. With that in mind, it might be a good time to review your asset allocation.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

So what do you think of this content? Follow us on social media and join the debate. We would love to hear your views. We're on X, LinkedIn and YouTube.