Do concentrated active managers produce higher returns?

- Robin Powell

- Apr 11, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 22, 2024

It's often suggested that, if you're going to use active funds, then you need to look for concentrated active managers who take large positions in a small number of stocks. But is it actually true? CRAIG LAZZARA from S&P Dow Jones indices explains why you may need to think again.

Anyone familiar with our SPIVA Scorecards will recognise that most active managers fail most of the time. Anyone familiar with active managers will recognise that they can be quite creative in proposing both excuses and remedies for this historical record. One of their most persistent suggestions, in fact, is that active management simply isn’t active enough, leading some asset owners to search for more exposure to concentrated active managers.

This approach is misdirected for at least three reasons:

First, it assumes that the level of a manager’s optimism about a stock predicts its future performance. The argument for concentration necessarily implies both that stock selection skill exists, and that it is particularly acute at its extremes. Not only, for example, must a manager be able to build a 50-stock portfolio that will outperform, he must also be able to identify which ten stocks of the initial 50 are the best of the best. For concentrated portfolios to outperform, both assumptions — that skill exists, and that it is acute at the extremes — must be true simultaneously. There is no evidence that either of them is. If it exists at all, the requisite skill must be quite rare. If this were not so, active funds would not be facing a performance challenge in the first place.

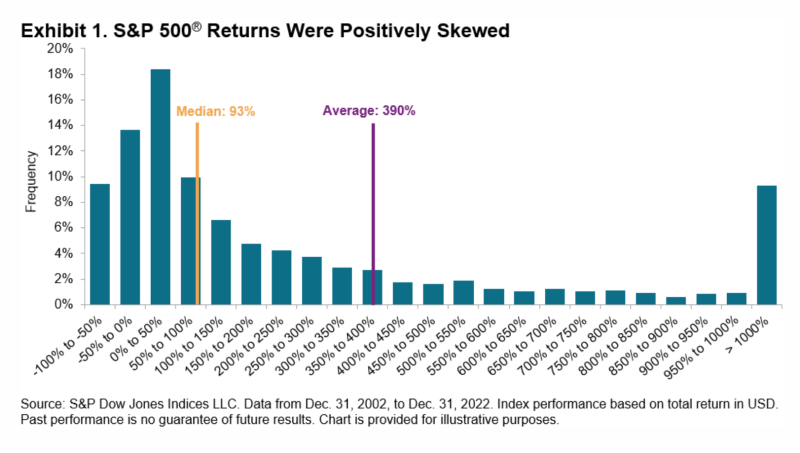

Second, under reasonable assumptions, concentrating equity positions raises the probability of underperformance. One of the most consistent characteristics of global equity markets is that returns are positively skewed — when graphed, they have a long right tail, as shown in Exhibit 1. This is intrinsically logical, since a stock can only lose 100%, but has unlimited upside.

For the 20 years ending in 2022, the median return of S&P 500 members (during their index membership) was 93%, far below the average return (390%). Only 31% of the index’s constituents outperformed the average stock. In such a market, a manager’s success is dependent on his ownership of a relatively small number of strong performers. The more concentrated a portfolio is, the less likely it is to own the big winners.

Third, concentrated portfolios make it harder to distinguish between signal and noise. While some managers may be skilful, none is infallible. A manager who is skilful but not infallible will benefit from having more, rather than fewer, opportunities to display his skill. A useful analogy is to the house in a casino: on any given spin of the roulette wheel, the house has a small likelihood of winning; over thousands of spins, the house’s advantage is overwhelming.

Skilful managers sometimes underperform; unskilful managers sometimes outperform. The challenge for an asset owner is to distinguish genuine skill from good luck. The challenge for a manager with genuine skill is to demonstrate that skill to his or her clients. The challenge for a manager without genuine skill is to obscure his or her inadequacy. Concentrated portfolios make the first two tasks harder and the third easier.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.