How good are analysts at forecasting earnings growth?

- Robin Powell

- Oct 18, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 8, 2024

By LARRY SWEDROE

In a recent article for The Evidence Based Investor I showed that while growth stocks have produced higher returns on assets and equities (i.e. they have been more profitable), and faster growth in earnings than value stocks, value stocks have provided higher returns over the long term. While that surprises many investors, it should not. The reason is that the expected rate of growth in future cash flows plays a pivotal role in investment analysis and valuations—the faster rate of growth in cash flows results in higher valuations (higher P/E ratios) for growth stocks versus value stocks. The article went on to show the evidence that while growth stocks did have higher growth in earnings, the persistence of abnormal earnings growth was not greater than would be randomly expected, leading to investor disappointment. In addition, their greater exposure to economic cycle risk results in investors demanding a risk premium for accepting value stocks’ incremental risks. And finally, the article discussed behavioural explanations for the higher returns of value stocks.

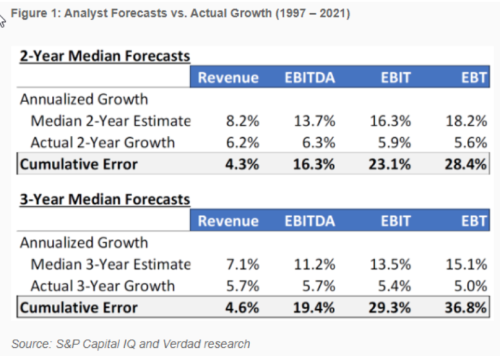

Thanks to Brian Chingono and Greg Obenshain of Verdad, we have another explanation — the inability of analysts to accurately forecast earnings growth. Using a database of all U.S. stocks from 1997 to 2021, they measured the median analyst estimate for growth over the next two to three years across a range of earnings metrics (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation , EBIT and EBT). They then compared these forecasts against the actual median outcomes over the next two to three years. As you can see in the tables below, not only did analysts’ forecasts systematically overshoot the actual outcomes, their forecast errors became larger the further down the income statement (earnings available to equity investors) and the further out in time.

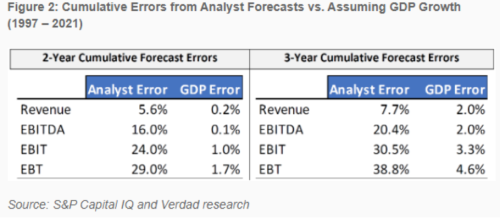

In fact, when Chingono and Obenshain replaced analyst forecasts with a naive estimate corresponding with long-term GDP growth (since 1947, U.S. GDP growth has averaged 6.3 percent per year on a nominal basis and 2.8 percent in real terms), they found that the naive forecasts produced far superior results. For example, while the cumulative three-year error of analyst forecasts of EBT was 36.8 percent, using the GDP measure resulted in a cumulative error of just 4.6 percent.

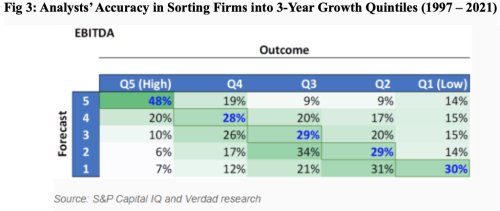

While logic and the empirical evidence make clear that it is difficult to see how the profitability of the business sector over the long term can grow much faster than overall gross domestic product, Chingono and Obenshain examined whether analysts could identify companies that would produce top quintile growth in earnings (buying only the leaders, not average companies), and, if they could, did that lead to superior performance? As you can see in the tables below, they found very little evidence to support that conclusion—analysts were less than 50 percent correct in predicting top quintile earnings growth over the following three years, and their success in forecasting the other quintiles was much worse.

Unfortunately, the bad news doesn’t end there because, if a stock is richly priced because analysts expect 20 percent annualized earnings growth over the next three years and the current price reflects that estimate, investors won’t earn a return premium unless its realized earnings growth exceeds 20 percent per year. On the other hand, if realized growth comes in below that, the price decline could be catastrophic (depending on the size of the miss). With that in mind, Chingono and Obenshain examined the median three-year forecasts and outcomes within each quintile of analyst expectations. They found that while analysts were generally correct (the highest-expectation stocks grew faster than the lowest-expectation stocks), their errors were significantly bigger in the higher-expectation quintiles than the lower-expectation quintiles, and their errors were also significantly bigger the further down the income statement (where it matters most). They also found that about two-thirds of the companies assigned by analysts to the lowest-expectation category delivered positive surprises over the next three years! In other words, abnormal earnings growth, whether high or low, tends not to persist.

Chingono and Obenshain’s findings are entirely consistent with other empirical research on this subject, including the 1999 study Forecasting Profitability and Earnings, the 2002 study The Level and Persistence of Growth Rates and the 2015 study Glamour, Value and Anchoring on the Changing P/E, which found: While some firms have grown at high rates historically, they are relatively rare instances; abnormally high and low earnings growth rates revert to the mean at very high rates (much faster than the market anticipates); and glamour investors anchor on the high P/E value for glamour shares while ignoring the high likelihood of future changes to the P/E ratio.

Investor takeaways

Value stocks have provided higher returns than growth stocks over the long term, with both risk- and behavioral-based explanations for the premium. Chingono and Obenshain provided another explanation, one that is likely the result of behavioral biases such as overconfidence in the ability of companies to persistently generate abnormal growth rates. In effect, they showed that one reason value investing has worked is that stocks with low growth expectations priced in are less likely to disappoint dramatically: “It’s one thing to miss the three-year EBITDA estimate by 8% in a cheap company that’s already priced for slower growth than inflation. It’s quite another scenario to miss the three-year EBITDA estimate by 68% in a company that’s priced to grow 5x faster than GDP.” Forewarned is forearmed.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.