Index concentration: why the Mag7 'problem' strengthens the case for indexing

- Robin Powell

- Sep 9, 2025

- 8 min read

Imagine walking into your local supermarket and finding the manager frantically reorganising the shelves. "We've got a serious problem," he explains, gesturing toward the front displays.

"Our bestselling products — bread, milk, bananas — are taking up too much space. Customers are spending most of their money on just a handful of items. This concentration is dangerous, so I'm moving them to the back and giving prime real estate to slower-moving specialty products instead."

You'd think he'd lost his mind. Yet this is precisely the logic behind one of the most persistent criticisms of index investing today: that the S&P 500's concentration in the so-called Magnificent Seven tech stocks makes indexing too risky.

The argument follows a seductive pattern. Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Tesla now represent roughly 30% of the S&P 500's market capitalisation. Critics wave this statistic like a red flag, declaring that such dominance by a small group of companies proves indexing has become a dangerous bet on a handful of tech giants. Better, they argue, to hand your money to active managers who can "diversify properly" by avoiding these concentrated positions.

This reasoning contains a fundamental flaw that becomes obvious once you examine the mathematics of market returns and the historical evidence of market leadership. Far from undermining the case for indexing, concentration actually strengthens it dramatically.

The 4% rule that changes everything

The most compelling evidence comes from Hendrik Bessembinder's groundbreaking research at Arizona State University. His analysis of US stock market returns from 1926 to 2023 reveals a startling truth: just 4% of stocks have been responsible for all the net wealth creation in the American stock market over nearly a century.

Let that sink in. Of the thousands of companies that have been publicly traded, only four out of every hundred have generated the returns that built long-term wealth. The other 96% either delivered mediocre performance or lost money entirely.

Bessembinder's latest study shows that just 17 US stocks delivered cumulative returns exceeding five million percent between 1925 and 2023. These aren't typos — these are the mega-winners that drove virtually all market gains. Miss these handful of companies, and your portfolio's long-term performance collapses.

This research transforms the concentration debate entirely. The Magnificent Seven aren't an aberration — they're exactly the type of companies that have always driven market returns. The "problem" of index concentration is actually the solution to successful long-term investing.

Why active managers consistently miss the winners

Terry Smith, once hailed as Britain's answer to Warren Buffett, provides a perfect case study in how even sophisticated stock-pickers struggle with concentration. His Fundsmith Equity fund delivered impressive early returns but has badly lagged the market since late 2021.

The primary culprit? Smith chose not to invest in NVIDIA, whose shares have soared since May 2023 as artificial intelligence transformed the technology landscape. "We do not own any NVIDIA," Smith wrote to shareholders, "as we have yet to convince ourselves that its outlook is as predictable as we seek."

Smith's caution sounds prudent, but it illustrates the fundamental challenge facing all active managers: identifying the 4% of stocks that will drive future returns is extraordinarily difficult. Even when managers own some winners, they typically underweight them. Smith holds Apple, but at just 1.4% of his fund compared to Apple's 6.6% weighting in the S&P 500. This "prudent diversification" away from market leaders systematically reduces returns.

Active managers face an impossible position sizing problem. Hold large positions in concentrated winners, and you're accused of taking excessive risk. Hold small positions, and you miss the returns that matter. Index funds solve this problem automatically by maintaining market-weight positions in all companies, ensuring they capture the full benefit when any stock joins the exclusive 4% club.

The historical pattern of market leadership

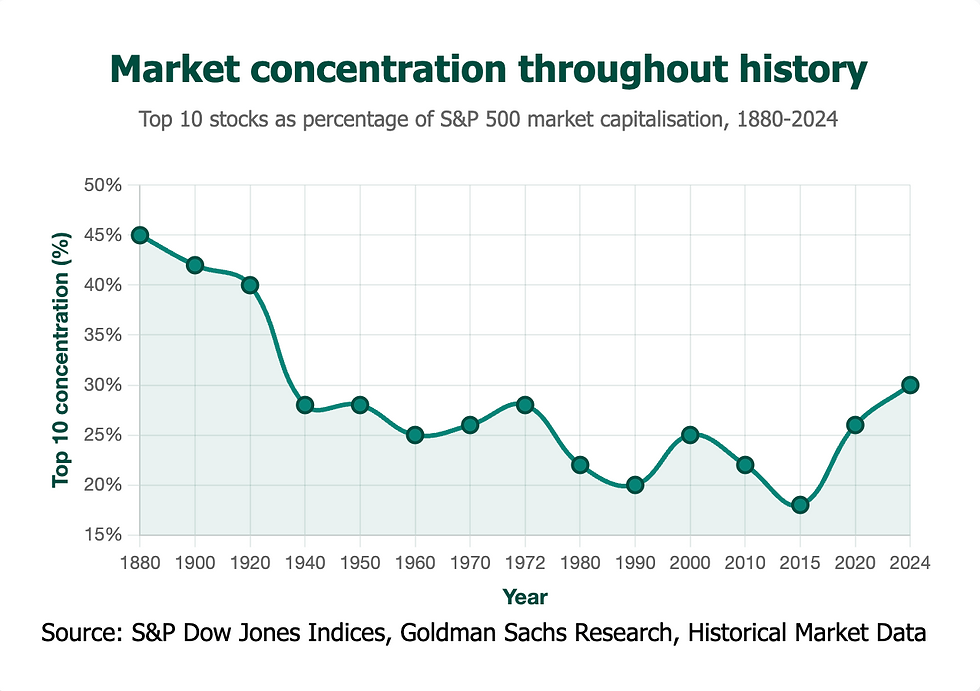

Index concentration isn't a modern phenomenon born of Big Tech dominance. Market leadership has been concentrated throughout history, often in the transformative industries of each era.

During the late 19th century, railroads dominated American markets. Union Pacific, Pennsylvania Railroad, and New York Central were the mega-caps of their day, with the top 10 companies representing over 40% of total market value. The early 20th century saw similar concentration in industrial giants like US Steel, Standard Oil, and AT&T, which controlled well over 40% of market capitalisation around 1910-1920.

The post-World War II boom concentrated leadership in companies like General Motors, DuPont, and Exxon. By the early 1950s, the top 10 stocks typically represented 25-30% of the market — virtually identical to today's levels. The famous Nifty Fifty era of the 1970s saw the top five stocks account for approximately 23% of the S&P 500, with the top 10 reaching around 28% of total market capitalisation.

More recent examples include the early 1960s blue-chip dominance and the FAANG-driven expansion of the 2010s. In each case, critics worried about excessive concentration, yet markets often delivered strong returns during and after these periods of narrow leadership. The 2010s concentration in Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google didn't end in a bubble burst — it coincided with a decade-long bull market that created enormous wealth for index investors.

The diversification myth that costs investors returns

Active managers promote a seductive narrative about "real diversification." They argue that by avoiding concentrated index positions, they're providing superior risk management through broader stock selection and sector allocation.

This argument collapses under scrutiny. First, active managers often create their own concentration risks by overweighting favoured sectors or investment themes while systematically avoiding the market's biggest winners. Second, their attempts to "improve" on market weighting consistently fail to deliver better risk-adjusted returns after fees.

Recent SPIVA data reveals the stark reality. Even in small- and mid-cap investing — supposedly active management's sweet spot — long-term success rates remain poor. In UK mid-cap funds, only 13.3% beat their benchmark over three years, and just 18.2% succeeded over 10 years. European small-cap managers fared slightly better over longer periods but still delivered coin-flip odds at best.

The mathematical reality is unforgiving: active managers must overcome their fees, transaction costs, and the drag of holding cash while consistently identifying future winners from the 4% of stocks that will drive returns. History shows this combination is extraordinarily difficult to achieve repeatedly.

Solving concentration concerns with index diversification

Investors genuinely concerned about index concentration have better solutions than fleeing to active management. The index fund universe offers multiple ways to diversify beyond large-cap dominance while maintaining the advantages of passive investing.

UK investors can access broadly passive small- and mid-cap exposure through vehicles like the Amundi Prime UK Mid and Small Cap UCITS ETF, which charges just 0.05% annually and provides instant diversification away from large-cap concentration. Vanguard's Global Small Cap Index Fund offers worldwide small-company exposure at 0.30%, while LGIM's UK Smaller Companies Index Fund tracks the FTSE Small Cap Index.

The arrival of Dimensional Fund Advisors in European markets provides another sophisticated option. The firm's upcoming small- and mid-cap value ETF, launching before year-end with an expected fee around 0.40%, combines Nobel Prize-winning academic research with systematic factor exposure. This represents genuine innovation in addressing concentration concerns through evidence-based diversification rather than expensive active management.

For investors seeking global small-cap value exposure immediately, Avantis's Global Small Cap Value UCITS ETF trades on the London Stock Exchange at 0.39% annually and is accessible through all major UK platforms including ISAs and SIPPs.

The mathematical advantage of guaranteed winner ownership

Index concentration creates a powerful mathematical advantage that active management cannot replicate: guaranteed ownership of all future mega-winners. When you buy an index fund, you automatically own every company that might join Bessembinder's exclusive 4% club.

Index concentration creates a powerful mathematical advantage that active management cannot replicate: guaranteed ownership of all future mega-winners.

This matters enormously because identifying future mega-winners in advance is essentially impossible. Did anyone predict in 1980 that Microsoft would become one of history's greatest wealth creators? Could investors in 1997 foresee Amazon's transformation from online bookshop to global technology colossus? Was NVIDIA's artificial intelligence dominance obvious when it was primarily known for gaming graphics cards?

Active managers face the impossible task of predicting which companies will generate the extreme returns that drive long-term wealth creation. Even exceptional managers like Terry Smith struggle with this challenge. But index investors don't need to predict anything — they simply own everything and let the market's natural selection process work in their favour.

The concentration in today's Magnificent Seven represents the market's collective judgment about which companies are creating the most value in the current technological revolution. Rather than fighting this verdict through active management, index investors benefit from it automatically.

Why index concentration validates efficient markets

The efficiency of index concentration becomes clear when you consider the alternative. If markets were truly inefficient and active managers could consistently identify mispriced opportunities, we'd expect to see widespread outperformance after fees. Instead, we observe the opposite: the vast majority of active funds underperform their benchmarks over time.

This pattern suggests that current index concentration reflects genuine economic value creation rather than speculative excess. The Magnificent Seven companies dominate indices because they've generated extraordinary growth in earnings, revenue, and innovation that translates into shareholder value.

Active managers who avoid these companies aren't providing superior risk management — they're fighting against the market's efficient price discovery mechanism. Their clients pay fees for the privilege of receiving lower returns through forced diversification away from the economy's most successful businesses.

Practical implementation for concentration-conscious investors

Investors can address concentration concerns systematically without abandoning indexing's advantages. A sensible approach might allocate 70% to broad market indices, 20% to small- and mid-cap index funds, and 10% to international developed or emerging market exposure.

This strategy maintains low costs, reduces concentration risk, and preserves the mathematical advantage of owning all potential future winners. The small- and mid-cap allocation provides exposure to companies that might grow into tomorrow's mega-caps, while international diversification reduces dependence on any single market's concentration patterns.

Timeline Portfolios' Classic range offers professional implementation of this approach through financial advisers, combining broad market exposure with small-cap and value tilts at total costs around 0.22-0.32% annually. For self-directed investors, combining low-cost ETFs achieves similar exposure with complete transparency and control.

The concentration advantage in perspective

Index concentration represents a feature, not a bug, of successful long-term investing. The market's tendency to concentrate returns in a small number of exceptional companies reflects the natural distribution of business success in competitive economies.

Rather than fighting this pattern through expensive active management, investors should embrace it through systematic index investing complemented by targeted diversification into smaller companies. This approach captures the mathematical advantage of guaranteed winner ownership while addressing legitimate concentration concerns through evidence-based portfolio construction.

The next time someone warns you about dangerous index concentration in the Magnificent Seven, remind them of a simple truth: these concentrated positions exist because these companies have created enormous value for shareholders. Index concentration doesn't weaken the case for passive investing — it proves why indexing works so well in the first place.

References:

Bessembinder, H. (2018). Do stocks outperform Treasury bills? Journal of Financial Economics, 129(3), 440-457.

Bessembinder, H. (2024). Long-term shareholder returns: Evidence from 64,000 global stocks. Arizona State University Working Paper.

S&P Dow Jones Indices. (2024). SPIVA Europe Scorecard: Year-End 2023. S&P Global.

Morningstar. (2024). Active/Passive Barometer: European Edition. Morningstar Direct.

PREVIOUSLY ON TEBI

FIND AN ADVISER

Investors are far more likely to achieve their goals if they use a financial adviser. But really good advisers with an evidence-based investment philosophy are sadly in the minority.

If you would like us to put you in touch with one in your area, just click here and send us your email address, and we'll see if we can help.