A diverse portfolio is a strong portfolio

Comments Off on A diverse portfolio is a strong portfolio

By CRAIG LAZZARA

We can think of an active equity portfolio as a combination of a benchmark (the S&P 500®, for example) and a set of active bets that measure the portfolio’s deviation from the benchmark. The relative size of the active bets is sometimes called “active share,” and is a convenient way to judge a manager’s aggressiveness. An active share of 0% is associated with an index fund; an active share of 100% implies that the manager has no holdings in common with his benchmark. (It may also imply that we’re using the wrong benchmark for the manager in question, but that’s another story.)

It’s been suggested that high active share is associated with outperformance, although the evidence on the question is far from conclusive. Although high active share may (or may not) be a necessary condition for active success, it cannot be a sufficient condition. Can an underperforming manager improve his results by randomly selling half the names in his portfolio, thus creating more concentration? Doing so will increase active share for sure, but it stretches credulity to think that such a course would automatically improve performance.

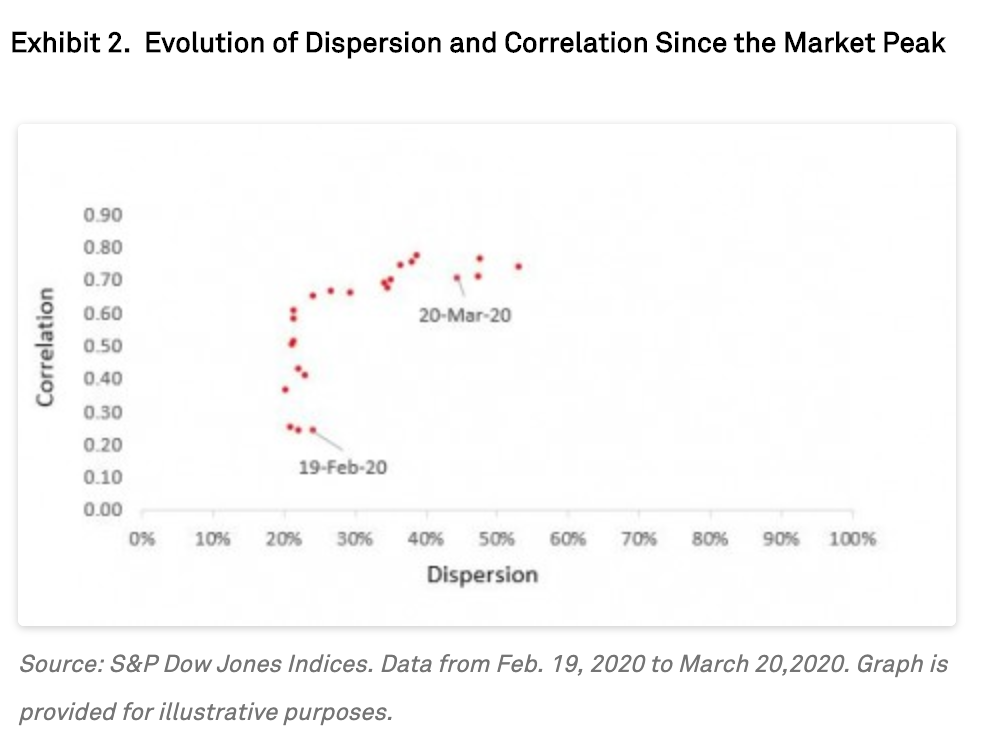

In our view, the stronger argument runs the other way: other things equal, more names are better than fewer. This is because stock market returns tend to be positively skewed. Rather than being symmetrically distributed around an average, return distributions typically have a very long right tail; a relatively small number of excellent performers has a disproportionate influence on the market’s overall return.

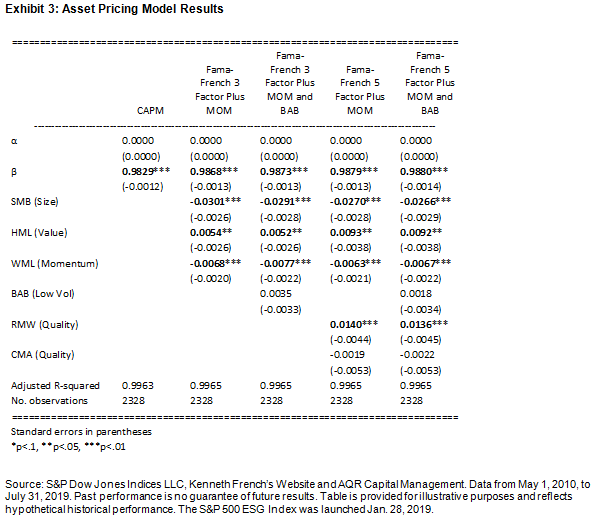

Exhibit 1 illustrates the skewness of the S&P 500 over the last 20 years. The median stock in the index returned 63%, while the index’s return was 322%. Only 22% of the names outperformed the index, which helps explain why active results have been so disappointing. When a randomly chosen stock has roughly one chance in five of beating an index fund, successful stock selection is very difficult. A portfolio manager who opts to concentrate his holdings will need a level of predictive accuracy that most portfolio managers demonstrably do not have.

Instead, the implication of Exhibit 1 is that more diversified portfolios, by including more stocks, stand a better chance of outperformance. Skewed returns mean that an active portfolio’s success depends on whether it is overweight a relatively small number of names. The more names a portfolio holds, the more likely it is to own one of the relatively small number of big winners.

Otherwise said: rather than picking the 50 stocks she likes the best and holding them, an investor benchmarked against the S&P 500 might be better served by eliminating the 50 stocks she likes the least and holding the other 450. True, active share would be lower for the larger portfolio. But the likelihood of owning one of the relatively rare big winners would be nine times as high. When returns are skewed, increasing diversity increases the odds of success.

CRAIG LAZZARA is Managing Director and Global Head of Index Investment Strategy at S&P Dow Jones Indices. This article was first published on the Indexology blog.

MORE FROM S&PDJI

For more valuable insights from our friends at S&P Dow Jones Indices, you might like to read these other recent articles:

Why even Buffett has been buffeted by the index

The case for looking beyond the S&P 500

The impact of style bias on the latest SPIVA data

Three reasons for active managers to feel positive

What does GameStop mean for market efficiency?

Is equal weighting worth considering?

WHAT TO READ NEXT

If you found this article interesting, we think you’ll enjoy these too:

The only right way to view an asset

The risks in buying individual stocks

Can machines identify winning fund managers in advance?

Can active managers time factor exposures?

The odds of outperforming through active management

Which is best for corporate bonds — active or passive?

FIND AN ADVISER

The evidence is clear that you are far more likely to achieve your financial goals if you use an adviser and have a financial plan.

That’s why we’re now offering a service called Find an Adviser.

Wherever they are in the world, we will put TEBI readers in contact with an adviser in their area (or at least in their country) whom we know personally, who shares our evidence-based investment philosophy and who we feel is best able to help them. If we don’t know of anyone suitable we will say.

We’re charging advisers a small fee for each successful referral, which will help to fund future content.

Need help? Click here.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXI